Forgetting is key to your brain’s capacity to remember

The brain is truly a marvel. A seemingly endless library, whose shelves house our most precious memories as well as our lifetime’s knowledge. But is there a point where it reaches capacity? In other words, can the brain be “full”?

The brain is truly a marvel. A seemingly endless library, whose shelves house our most precious memories as well as our lifetime’s knowledge. But is there a point where it reaches capacity? In other words, can the brain be “full”?

The answer is a resounding no, because, well, brains are more sophisticated than that. A study published in Nature Neuroscience earlier this year shows that instead of just crowding in, old information is sometimes pushed out of the brain for new memories to form.

Previous behavioural studies have shown that learning new information can lead to forgetting. But in this study, researchers used new neuroimaging techniques to demonstrate for the first time how this effect occurs in the brain.

Storing information alone is not enough for a good memory

The paper’s authors set out to investigate what happens in the brain when we try to remember information that’s very similar to what we already know. This is important because similar information is more likely to interfere with existing knowledge, and it’s the stuff that crowds without being useful.

To do this, they examined how brain activity changes when we try to remember a “target” memory, that is, when we try to recall something very specific, at the same time as trying to remember something similar (a “competing” memory). Participants were taught to associate a single word (say, the word sand) with two different images—such as one of Marilyn Monroe and the other of a hat.

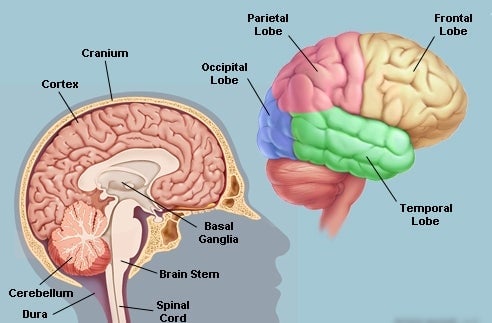

They found that as the target memory was recalled more often, brain activity for it increased. Meanwhile, brain activity for the competing memory simultaneously weakened. This change was most prominent in regions near the front of the brain, such as the prefrontal cortex, rather than key memory structures in the middle of the brain, such as the hippocampus, which is traditionally associated with memory loss.

The prefrontal cortex is involved in a range of complex cognitive processes, such as planning, decision making, and selective retrieval of memory. Extensive research shows this part of the brain works in combination with the hippocampus to retrieve specific memories.

If the hippocampus is the search engine, the prefrontal cortex is the filter determining which memory is the most relevant. This suggests that storing information alone is not enough for a good memory. The brain also needs to be able to access the relevant information without being distracted by similar competing pieces of information.

Better to forget old memories

In daily life, forgetting actually has clear advantages. Imagine, for instance, that you lost your bank card. The new card you receive will come with a new personal identification number (PIN). Research in this field suggests that each time you remember the new PIN, you gradually forget the old one. This process improves access to relevant information, without old memories interfering.

And most of us will be able to identify with the frustration of having old memories interfere with new, relevant memories. Consider trying to remember where you parked your car in the same carpark you were at a week earlier. This type of memory (where you are trying to remember new, but similar information) is particularly susceptible to interference.

When we acquire new information, the brain automatically tries to incorporate it within existing information by forming associations. And when we retrieve information, both the desired and associated but irrelevant information is recalled.

The majority of previous research has focused on how we learn and remember new information. But current studies are beginning to place greater emphasis on the conditions under which we forget, as its importance begins to be more appreciated.