The unique challenges of a first-generation college student

First-generation college students, or students whose parents have not earned a four-year degree, face unique psychological challenges.

First-generation college students, or students whose parents have not earned a four-year degree, face unique psychological challenges.

Although perhaps supportive of higher education, their parents and family members may view their entry into college as a break in the family system rather than a continuation of their schooling.

In families, role assignments about work, family, religion and community are passed down through the generations creating “intergenerational continuity.” When a family member disrupts this system by choosing to attend college, he or she experiences a shift in identity, leading to a sense of loss. Not prepared for this loss, many first-generation students may come to develop two different identities—one for home and another for college.

As a former first-generation college student who is now an associate professor of education, I have lived this double life. My desire to help other first-generation students resulted in research that provides insights into the lived experiences of first-generation students at Wheelock College, a small college in Boston, Massachusetts, that has a high percentage of first-generation students. In 2010, 52% of our incoming undergraduates were first-generation college students.

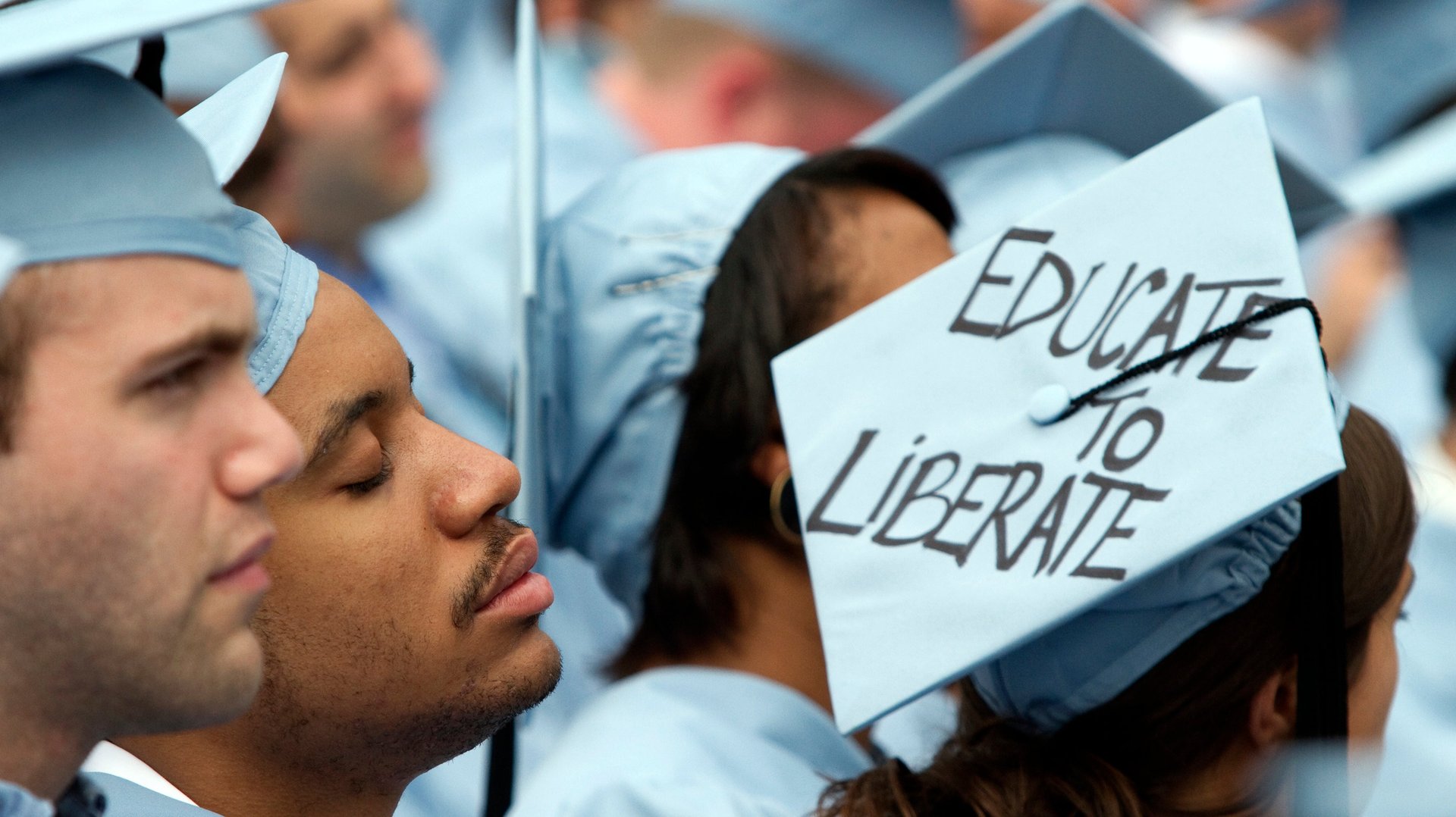

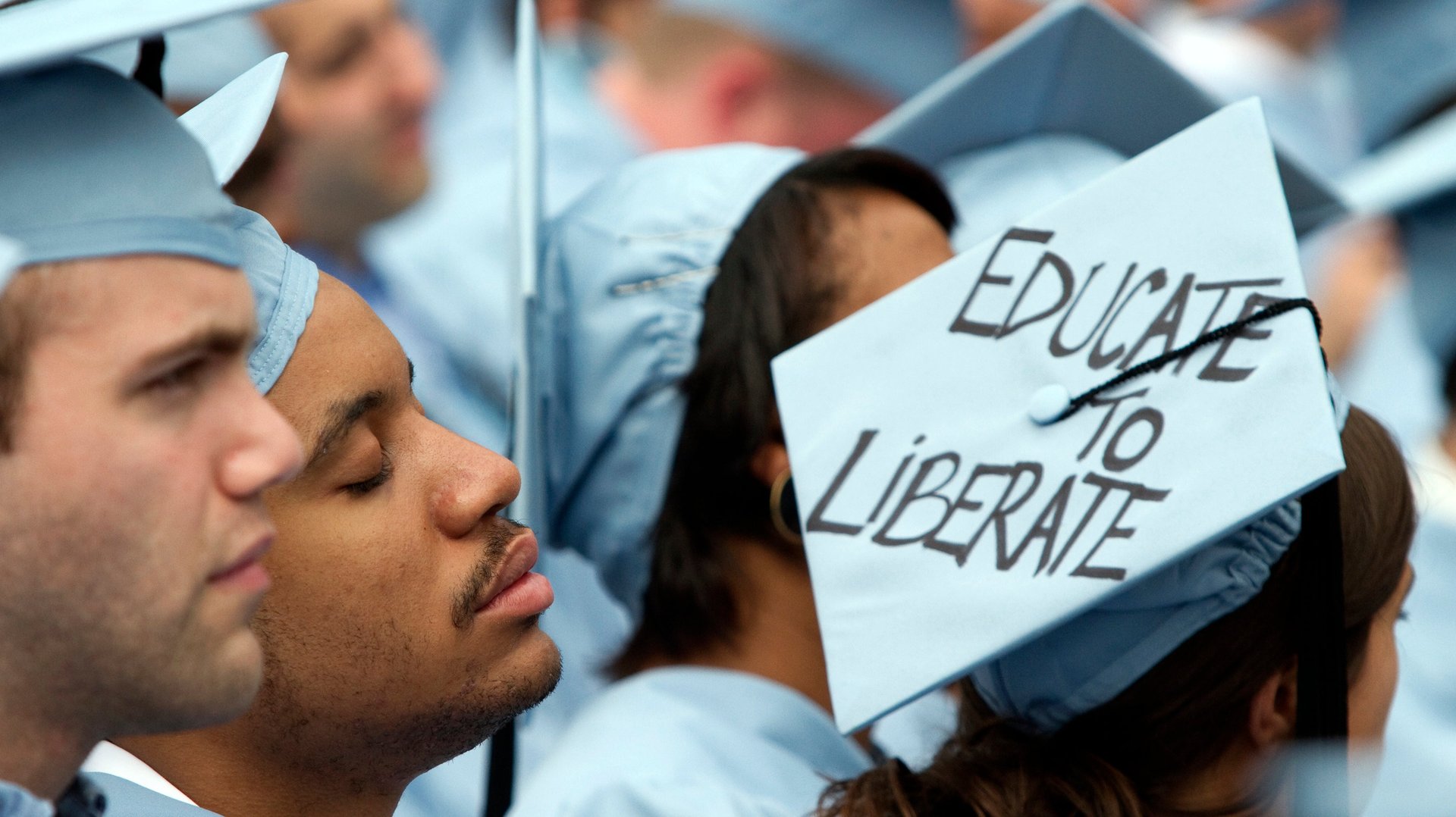

Nationally, of the 7.3 million undergraduates attending four-year public and private colleges and universities, about 20% are first-generation students. About 50% of all first-generation college students in the US are low-income. These students are also more likely to be a member of a racial or ethnic minority group.

Why they decide to go to college

Most first-generation students decide to apply to college to meet the requirements of their preferred profession. But unlike students whose parents have earned a degree, they also often see college as a way to “bring honor to their families.”

In fact, studies show that a vast majority of first-generation college students go to college in order to help their families: 69% of first-generation college students say they want to help their families, compared to 39% of students whose parents have earned a degree. This desire also extends to the community, with 61% of first-generation college students wanting to give back to their communities compared to 43% of their non-first-generation peers.

And while their families often view them as their “savior,” “delegate,” or a way out of poverty and less desirable living conditions, many first-generation students struggle with what has been described as “breakaway guilt.”

Their decision to pursue higher education comes with the price of leaving their families behind.

They may feel they’re abandoning parents or siblings who depend on them. And families too may have conflicted feelings: first-generation college students’ desire for education and upward mobility may be viewed as a rejection of their past.

Perceived as different at home and different at school, first-generation college students often feel like they don’t belong to either place.

The challenge of higher education is to recognize the psychological impact that first-generation status has on its students and to provide help.

First-generation students lack resources

Not all first-generation college students are the same, but many experience difficulty within four distinct domains: 1) professional, 2) financial, 3) psychological and 4) academic.

Most of all, they need professional mentoring. They are the ones most likely to work at the mall during the summer rather than in a professional internship. They can’t afford to work for free, and their parents do not have professional networks.

Often, first-generation students apply only to a single college and do that without help. They can’t afford multiple application fees and they are unsure of how to determine a good fit, as their parents have not taken them on the college tour.

Many first-generation students fill out the financial aid forms themselves. As one college student explained:

“They put all these numbers down and expect you to know what each one means. My mother doesn’t know and she expects me to find out and then tell her how it all works.”

First-generation students worry about the families they leave behind and try to figure out how to support them.

One first-generation student managed to enroll in college but was still worried about her mother’s lack of support. Miles away from home on a college campus for the first time, she divided her time each semester between paying her parents’ bills online and completing her assignments. Her parents didn’t own a computer or know how to use one.

The stigma is considerable

Colleges need to recognize that first-generation students do not easily come forward to seek help.

Even though there are many successful former first-generation role models, such as first lady Michelle Obama, US Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor and US Senator from Massachusetts Elizabeth Warren, there is considerable stigma associated with FG status.

As a result, some first-generation college students may choose to remain invisible. Once they identify, their academic ability, achievement and performance may be underestimated by others. Their background is viewed as a deficit rather than a strength. And they are unnecessarily pitied by others, especially if low-income.

In extreme cases, other students and faculty may question their right to be on campus. Low-income, first-generation college students may arrive to college with fewer resources and more academic needs, making them targets for discrimination.

In a recent New York Times video on first-generation students at Ivy League colleges, one such student at Brown University who was born in Colombia told faculty that she was from New Jersey to avoid having to reveal that she was a first-generation college student.

But, there is another side to the story as well.

There are first-generation college students who view their status as a source of strength. It becomes their single most important motivator to earning their degree. These students are driven and determined. They can perform academically in ways that are equal to or even better than students whose parents have earned a degree.

These students too may benefit from a support group to help alleviate the internal pressure they place on themselves to succeed.

How colleges can help

First-generation college students need customized attention and support that differs from students whose parents have earned a degree. They need to feel like they belong at their college or university and deserve to be there.

Higher education, with its unique culture, language and history, can be difficult for first-generation college students to understand. Students whose parents have attended college benefit from their parents’ experiences.

They come through the door understanding what a syllabus is, why the requirement for liberal arts courses exists and how to establish relationships with faculty. They can call their parents to ask for help on a paper or to ask questions about a citation method. They can discuss a classic novel they have both read.

This first-generation research has raised awareness on the Wheelock campus that has led to positive change. In 2014,the college applied for a First In the World federal grant to help implement a new program. Though we were not awarded a grant in the first round of competition, we will continue to seek funding.

Colleges and universities have the ability to redesign their institutional cultures, teaching practices and academic support services to be more inclusive of first-generation college students.

For instance, they can offer required courses in a variety of different formats (hybrid, on-line, face-to-face) and timings (between semesters, during summers) to help FG students reduce degree completion time and save money.

They can recruit former first-generation faculty members to advise and mentor students. A web page for first-generation students and families can be created that features success stories, user-friendly financial aid as well as scholarship information, and links to other opportunities.

With the right support from institutions of higher education, first-generation students can earn their degree, reinvent themselves and reposition their families in positive ways for generations to come.