The US is pulling back on its attempt to export insane drug prices to the world

One of the major sticking points of the Trans-Pacific Partnership 12-nation trade deal has been the United States’ attempt to include protections for drug prices. American negotiators seem to have given up (paywall) on part of that plan, which would have allowed drug companies to appeal prices they felt were too low when set by governments elsewhere. But according to a leaked document published in the New York Times (paywall), they’re still angling to require governments to disclose how they arrived at price controls and reimbursement rates for specific drugs—a proposal that is profoundly disliked by public health officials, and by other countries involved in the negotiations.

One of the major sticking points of the Trans-Pacific Partnership 12-nation trade deal has been the United States’ attempt to include protections for drug prices. American negotiators seem to have given up (paywall) on part of that plan, which would have allowed drug companies to appeal prices they felt were too low when set by governments elsewhere. But according to a leaked document published in the New York Times (paywall), they’re still angling to require governments to disclose how they arrived at price controls and reimbursement rates for specific drugs—a proposal that is profoundly disliked by public health officials, and by other countries involved in the negotiations.

The American negotiators may have a tough time lining up support for the so-called “transparency annex”—in large part because the United States has drug prices that are hugely out of step with the rest of the world.

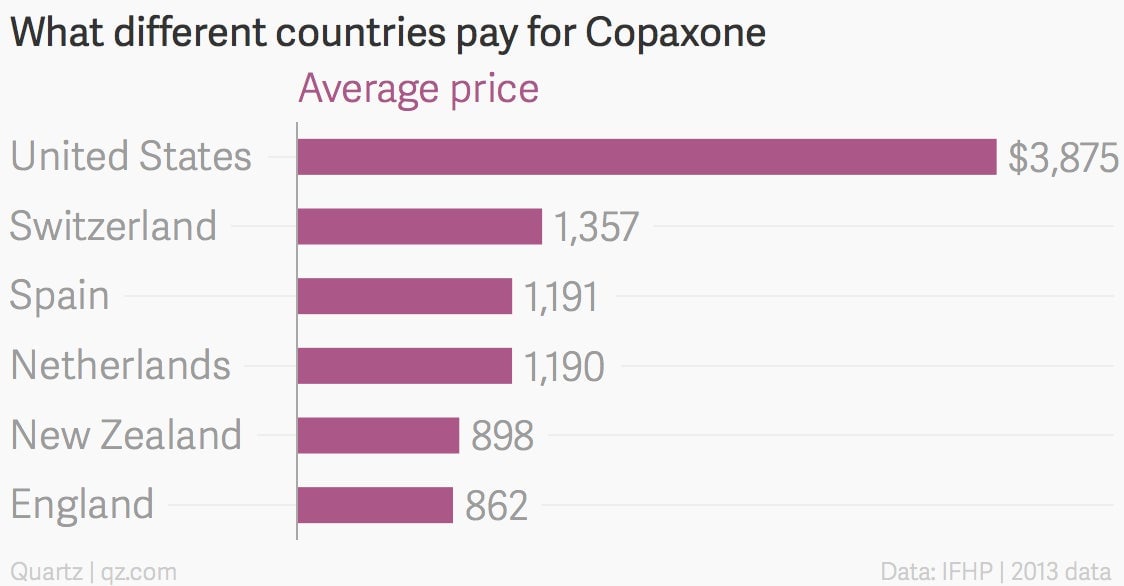

For example, here’s what private insurers paid on average in 2013 for Copaxone, an expensive drug for multiple sclerosis according to the International Federation of Health Plans (pdf). Private sector prices in England, Switzerland, and New Zealand are based on what the public sector pays:

Drug makers claim the prices are kept high in order to cover the cost of research. They’re higher in the United States in part because the biggest government payers aren’t permitted to negotiate prices. Other countries, notably potential trade pact signatories like New Zealand, are more muscular negotiators that hide the way they formulate their drug reimbursement rates in order to maintain leverage with the drug makers.

Pharmaceutical companies are fighting intensely on this trade deal (they’ve lobbied far more than other industries with something at stake in the pact). Brand-name makers want as much price protection as they can get, while generic drug makers are unhappy that the pact would weaken restrictions on direct-to-consumer drug marketing. (The restrictions are common around the world but do not exist in the United States, where heavy marketing is a major way drug companies keep branded sales up even when there are cheaper alternatives available.)

Though the step back from outright price protection means the TPP likely won’t be as good a deal for drug makers as it might have been, opening up pricing methodology to these companies and adding a dispute-and-appeal mechanism to the process, as the US proposes, may give them more opportunities to push prices upward around the world.