Tiger sharks’ refined palates may be sending them on a 7,500-km migration

Tiger sharks aren’t known to be picky eaters. As apex predators, they’ll eat just about anything. As long as they can swallow it, it’s fair game. In fact, they’ve even earned themselves the nickname “wastebucket of the sea,” according to National Geographic.

Tiger sharks aren’t known to be picky eaters. As apex predators, they’ll eat just about anything. As long as they can swallow it, it’s fair game. In fact, they’ve even earned themselves the nickname “wastebucket of the sea,” according to National Geographic.

But it turns out they may be destination diners—traveling thousands of kilometers for a change of cuisine.

For years, scientists assumed that these animals were coastal creatures that dined on whatever they found nearby. But new research from Nova Southeastern University in Florida suggests that tiger sharks actually migrate 7,500 km (4,660 miles) a year, from the Bahamas in the winter to as far north as the open ocean off the coast of Connecticut over the summer.

“These animals are really quite amazing in what they do,” Mahmood Shivji, director of the Guy Harvey Research Institute at Nova Southeastern University and one of the co-authors of the study told Quartz.

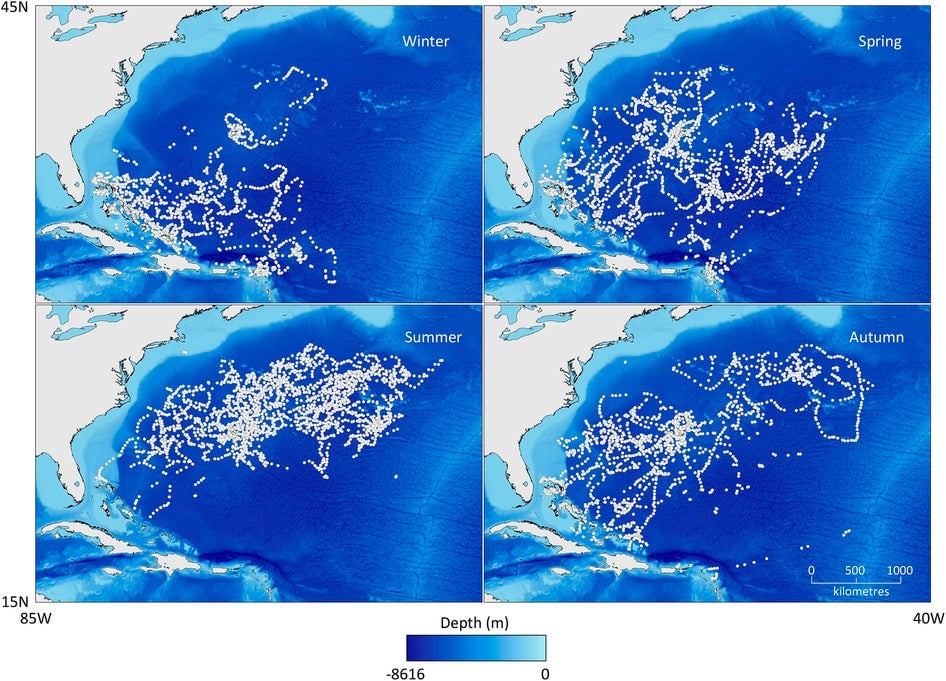

Researchers tagged 24 tiger sharks, most of them male, near the Bahamas from 2009 to 2011. The tracking devices on the sharks’ fins pinged satellites with their locations each time they breached the surface.

Over three years, researchers observed these sharks swimming the same routes between two drastically different marine environments. In the Bahamas, they get a bustling coral reef environment; up north, they’re in the open ocean. Why the change of scenery?

Well, scientists aren’t sure, but it could be to dine on a diversity of food: In the summer, young loggerhead turtles, which tiger sharks have been known to eat, also migrate north, but these turtles can also be found further south. Among the next steps of this research will be trying to figure out just why these animals go so far each year.

What’s clear, however, is that these sharks’ presence in both environments should be protected, Shivji said.

“As apex predators, the presence of tiger sharks—and other large sharks—is vital to maintain the proper health and balance of our oceans,” said Shivji. “That’s why it’s so important to conserve them, and understanding their migratory behavior is essential to achieving this goal.”