Charting corporate America’s formidable, but largely inaccessible, cash pile

The figure $1.8 trillion represents a lot of money. It looks particularly massive written out in full: $1,800,000,000,000.

The figure $1.8 trillion represents a lot of money. It looks particularly massive written out in full: $1,800,000,000,000.

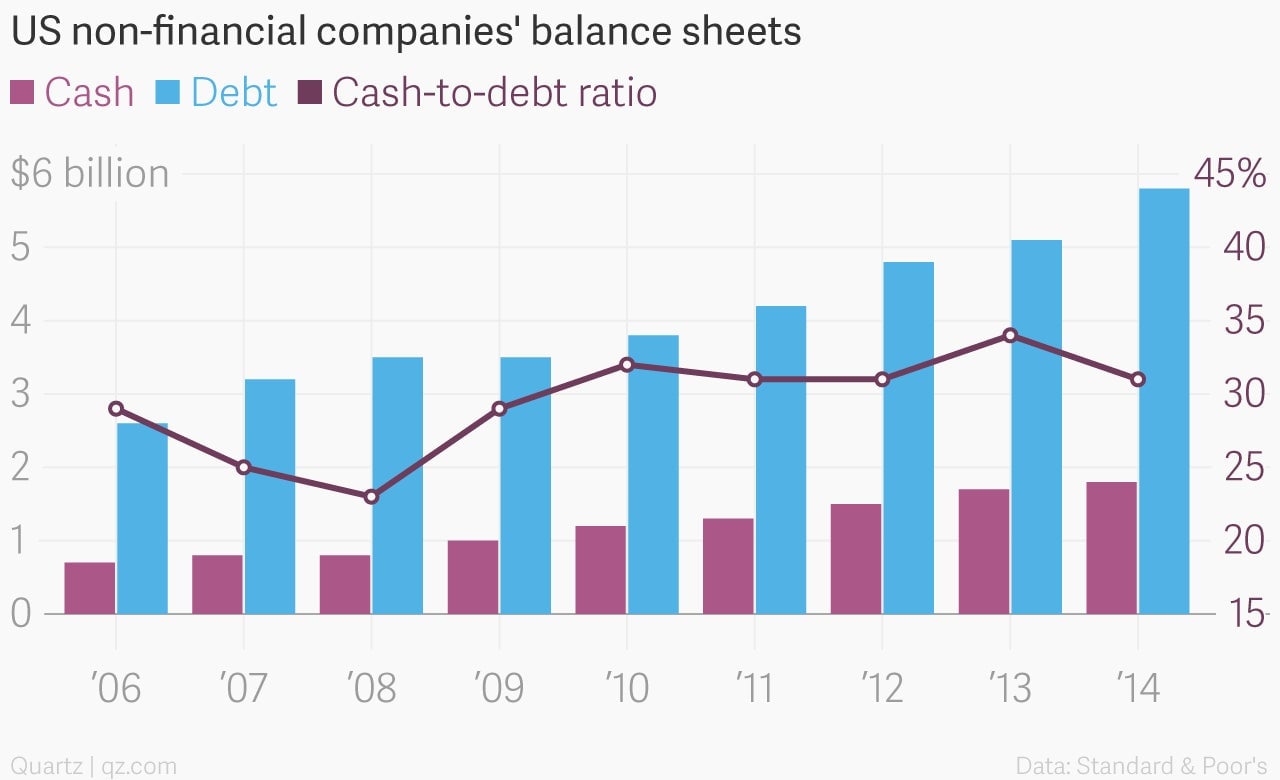

That’s how much cash American companies (excluding banks) were sitting on at the end of last year, according to Standard & Poor’s. This was up 5% on the year before, the latest in a string of records set since the financial crisis brought a new conservatism (some would call it fear) to corporate boardrooms:

Despite these cash hoards, companies have gone on an even bigger bond binge—debt rose three times as fast as cash in 2014. Over the past five years, S&P says, American firms have added $2 trillion in new debt to their balance sheets, outstripping the $600 billion gain in cash and keeping companies’ cash-to-debt ratio steady:

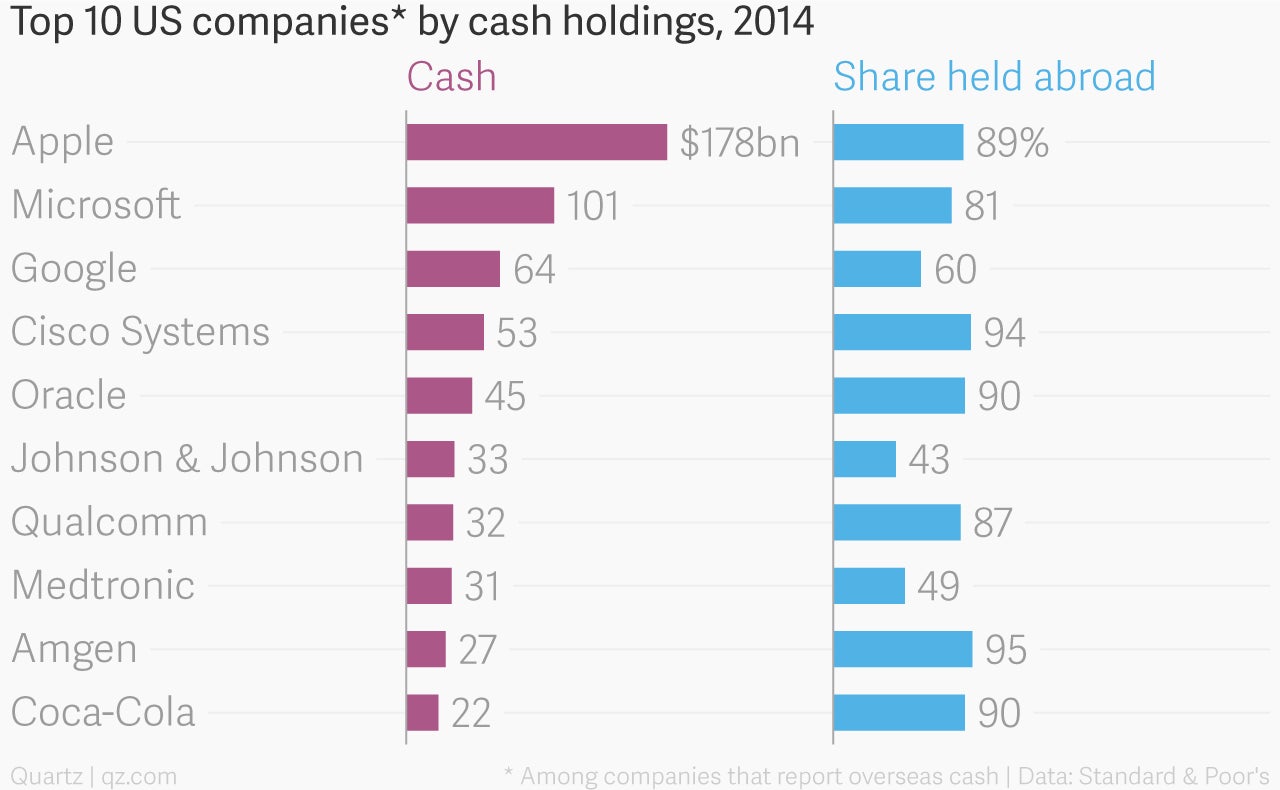

Low interest rates are tempting, but why borrow so much when there’s a large mountain of cash to mine? One reason is that cash holdings are heavily concentrated—the top 25 companies, out of 2,000 analyzed by S&P, hold half of all cash. (Apple alone is sitting on 10% of the total.) Another reason is that the vast majority of this cash is held outside of the US:

Instead of repatriating this money and taking a 35% tax hit, even the most cash-rich companies are borrowing to pay for boosting dividends, buybacks, and other returns for holders of their US-listed shares. S&P calls this “synthetic cash repatriation,” in which a company’s growth in cash generated abroad is matched almost by a similarly-sized rise in debt at home.

When the Federal Reserve starts raising interest rates, probably later this year, juicing shareholder returns with debt in this way will become less attractive. Then, unless the US government announces some sort of tax holiday for repatriated cash, it will be tough to keep the gravy train going without denting a company’s creditworthiness. In the meantime, companies will need to figure out something else to do with all that foreign cash to make shareholders happy.