My black hair: a tangled story of race and politics in America

“My Black Hair” is from Me, My Hair and I: Twenty-seven Women Untangle an Obsession, ed. Elizabeth Benedict (Algonquin 2015). You can visit the Facebook page for the book here.

“My Black Hair” is from Me, My Hair and I: Twenty-seven Women Untangle an Obsession, ed. Elizabeth Benedict (Algonquin 2015). You can visit the Facebook page for the book here.

If you are a Black woman, hair is serious business. Your hair is considered by many the definitive statement about who you are, who you think you are, and who you want to be. Long, thick, straight hair has for generations been considered a down payment on the American Dream. “Nappy” hair, although now accepted in its myriad forms, from the natural to twists and locks, has long been and remains a kind of bounced check on the acquisition of benefits of that same enduring cultural mythology. Like everything else about Black folk, Black people’s—and especially Black women’s—hair is knotted and gnarled by issues of race, politics, history, and pride.

Who would think that the family kitchen would double as a torture chamber? We think of the kitchen as the locus of nourishment, satisfaction, and family good times. But for generations of young Black girls, the family kitchen was associated with pain and fear, tears and dread. The kitchen was where, as a young girl, I got my hair “straightened.” My coarse, sometimes called “kinky” or “nappy,” hair, which was considered “bad” hair, got straightened with an iron comb that had been heated over a burner on the stove. It was made straight, as in no longer coarse, crooked, or “bad.” Straight, as in the admonition I often heard shouted at children who were misbehaving, “Straighten yourself out.” Ironically, “the kitchen” was also the name for the patch of unruly hair at the nape of the neck that was often most resistant to the magic of the hot comb.

Our kitchen in Washington, DC, smelled of smoke, burned hair, and Dixie Peach hair pomade, applied with my mother’s fingers onto my scalp. Sometimes the “hot comb” was dipped into the hair pomade and then applied to my hair. My mother, like so many mothers, thought this was an art or a science, but in reality it was haphazard, even dangerous work when performed by amateurs. The result of this laborious and often, for me, degrading ritual was straight hair but burned ears, neckline, forehead and scalp—all in the quest for what we called then, and many still call, “good hair.”

I remember hating the every-two-week ordeal, or sometimes even more often, if a “touch-up” was required. Maybe my hair got wet in the rain, maybe I sweated too much playing outside, maybe, God forbid, I went swimming without a swim cap, and then we were back to square one. Back to that awful, horrible place where my hair was on my head in its natural state, not hurting me or anybody else, but coarse, tightly curled, and, to the eyes of so many around me, unacceptable. The process of losing the straightness of the hot comb was even called “going back.” I got the message early on. I was not to face the world until my hair looked as near as it could to “good hair,” also known as “White girl’s hair.” Is it any wonder that I soon developed the habit of standing in front of my mother’s gilt-edged mirror with her silk scarves pinned on my head and imagining that those scarves were my real hair and that I had been transformed into Cinderella and Snow White? I spent countless hours alone in front of that mirror, hypnotized by what I wished for and what my imagination had made real. To have a White girl’s hair.

What happened to me in my mother’s kitchen was part of the generations-old tradition and requirement in the Black community. For women and men to be accepted by and successful in both the Black and the White worlds, we had to look, either through hair texture, skin color, or phenotype, like Whites. Of the three, hair texture has always been the easiest to change.

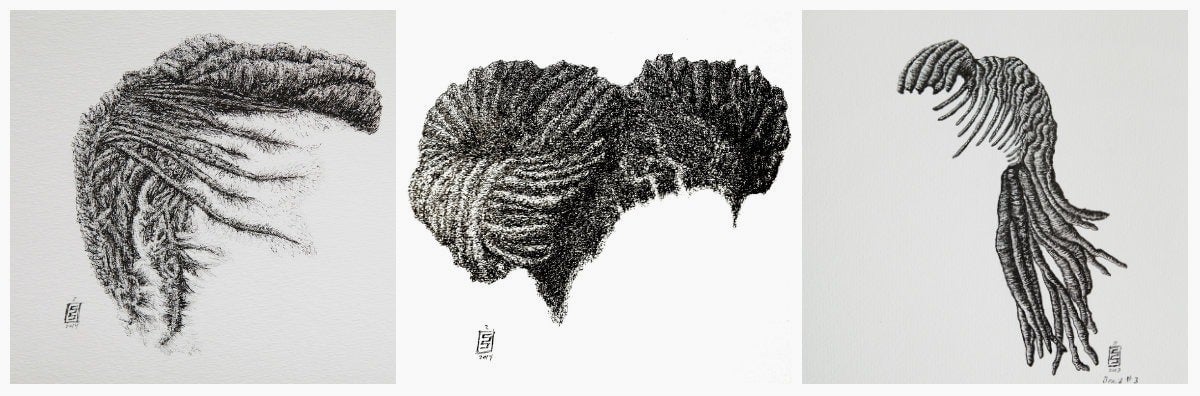

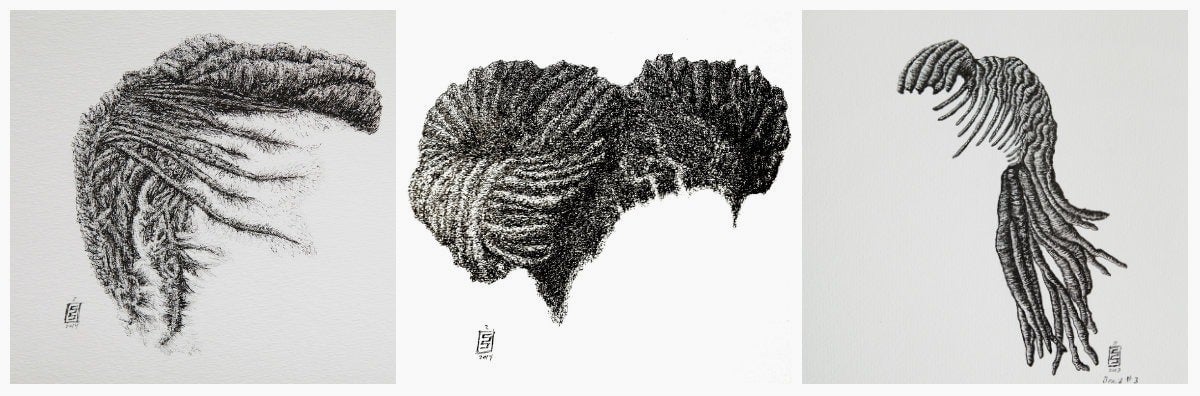

Today, as Black women in America spend half a trillion dollars a year on weaves, wigs, braids, and relaxers, that 1950s fantasy lives on for new generations of Black women, who can now simply, easily, and cheaply buy what I wished for back then. Little Black girls still get the message that their hair needs to be tamed, but they don’t wince and shrink as the hot comb nears their heads. As early as four or five years old, they are forced to endure “relaxers,” a process in which harsh chemicals applied to their natural hair do what the hot comb did for me. And their tender young hair may not be strong enough yet to endure chemicals that are toxic and that with years-long use have raised questions about long-term health effects. Or long artificial extensions are braided into their natural hair, sometimes so tightly that scalp damage can occur.

At about the age of 12, I graduated from our kitchen to the beauty parlor on 14th Street, where there were grown women in white uniforms—the professionals—who washed my hair and straightened it without the pain. Sitting in their midst for hours at a time, I heard grown women gossip about men and husbands and other women and jobs they hated and grown children who had turned out no good and a Temptations concert at the Howard Theatre. Going to the beauty parlor was as much about growing up and being initiated into the culture of grown Black women as it was about my hair. And everyone else’s. The beauticians could brutally joke about women with short hair. That was the worst sin, for a woman’s worth in the Black community, and all over the world, is determined by the length of her hair. “Good hair”—in case I didn’t know by now—was straight, thick, and long. In the beauty parlor, I felt grown up and accepted into the real world of Black hair culture, with the caveat that I knew mine would never be good enough. All the women in my community who were considered the most beautiful had straight hair, women like Lena Horne and Dorothy Dandridge. Where would I fit in, how would I fit in, with my short, coarse hair and brown skin? And even when my hair was straightened, it always “went back” to its natural state. In a reprise of the famous test by sociologist Kenneth Clark that revealed that little Black girls chose White dolls over Black dolls, when little Black boys were tested to see which dolls they preferred, the boys routinely chose the Black dolls, which all had smooth hair, because, they said, of their hair. For boys, the magic of straight hair could triumph over the negative connotations of brown skin.

What all this tells us is that hair is not benign, it is important and potent. In the book Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America, Lori L. Tharps and Ayana D. Byrd cite the work of the anthropologist Sylvia Ardyn Boone, who found that among the Mende tribe of Sierra Leone, “’big hair, plenty of hair, much hair,’ were the qualities every woman wanted,” and that “unkempt, ‘neglected,’ or ‘messy’ hair implied that a woman either had loose morals or was insane.” Traditionally in the Black community, mothers were and still are judged by the state of their daughter’s hair. I remember as a child the worst judgments of adult women being reserved for women whose daughters left the house with “nappy” or indifferently braided hair. This was a dereliction of parental duty that was considered nearly a form of child abuse. A Washington Post article about a White gay couple who had adopted a little Black girl cited an incident in which a Black woman, seeing the child on the subway with her two dads, could no longer bear the sight of her amateurish braids and left her seat and began braiding the girl’s hair.

For Black women, hair is not just our crowning glory, it is an expression of our souls. The furor over the hair of the young Olympic gymnast Gabrielle Douglas in the summer of 2012, was largely a Black female reaction to what some women saw as her “nappy hair.” The young teenager gave a brilliant performance, and yes, at times, with the exertion required, her hair did not look as “neat” as her White teammates’. Twitter and Facebook exploded with negative comments from some Black women, prompting a mainstream media discussion about Black women and their hair. Media as diverse as the Huffington Post, the Daily Beast, and Us Weekly covered the controversy over what a small but vocal sect of the Black female online community dubbed “messy” and “unkempt” hair. Douglas’s mother was forced to respond to the court of public opinion and post on the internet explanations and apologies for “what happened to Gabby’s hair.”

Traditionally, among many African groups, a person’s spirit is supposedly nestled in the hair, and the hairdresser is considered the most trustworthy individual in society. Clearly, African American attitudes about hair have been shaped by our living and vibrant cultural heritage, as well as by the requirements of trying to overcome oppressive attitudes about how Black people should look, think, act, and live. The “beauty parlor” and the barbershop remain among the most important institutions in the Black community. They are where we gossip, make friends, and talk politics outside the view and dominion of Whites, and where in many cases we have our confidence and self-esteem restored.

In the 1960s, hair became a form of political and cultural statement and protest. Everyone was letting his or her hair grow out or grow long, men and women, Black and White. The first time I ever liked my face or my hair was when I looked at myself in the mirror the day that I got my natural. I was an 18-year-old freshman who had entered American University five months after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The world was one of riots and rage and questioning everything from why Blacks had so little power, to why we were in Vietnam, to why Blacks had to look like Whites to be considered beautiful. It was a world of new kinds of questions and answers. Black suddenly became beautiful. I looked around and liked what I saw on the heads and on the faces of my Black female friends and peers who wore Afros. The natural hairstyle showcased their faces, and they were faces that seemed to be proud and confident. That is what I wanted to be. It was as if I had never before really seen my face that day I looked in the mirror. My first natural was a delicate, short, close-cropped affair, and the hair that I had hated and been on a quest to change suddenly seemed so lovely, so perfect. My family was aghast. I withstood teasing, and threats from my father to cut me off financially, all because of my hair. But for the first time in my life, I accepted my hair and myself.

The natural hairstyle ultimately inspired a resurgence of African-inspired hairdos: twists, cornrows, and locks that had a long history among Black women. This simple hairdo laid down a challenge to the central tenet of Black hair and all it stood for—that it was bad and should be rejected. The natural required care but not torturous care. And for me, the fact that my hair became the backdrop for my face, rather than the other way around, was so satisfying. The impact of the natural lasted about a decade. Then straight hair came back with a vengeance, while I kept my own hair natural, except for one or two times when I used a relaxer just for a change. But the chemicals always damaged my hair. The natural revealed, in ways that more traditional styles did not, what I now had come to know was an attractive face. It fit my busy lifestyle, and I liked the way I looked and felt wearing a natural—free and comfortable in my skin.

Whatever Black women do to their hair is controversial. The straightening of Black hair was controversial when first introduced at the turn of the 20th century. The technique was loudly criticized by the Black elite, even though many of them had straight hair that afforded them higher levels of acceptance by Whites than other Blacks received. When Blacks moved north during the Great Migration, women with braided hair or unstraightened hair were criticized as “country” and considered an embarrassment to their recently migrated yet suddenly urbanized cousins. Fast-forward half a century, and the Afro and natural were in some corners criticized as unkempt and uncivilized. Even today, many feel that natural hair is questionable as a legitimate hairstyle. The talk show host Wendy Williams criticized the actress Viola Davis so virulently for wearing her hair in a natural style to the Oscars in 2012, you would have thought she had attended the ceremony with a bag on her head. Recently, I was invited to speak to a group of high school girls who wanted to wear natural hair and who had formed a support group to sustain them in their decision. They shared heartbreaking stories of parents and friends who questioned their judgment because of this choice and predicted all manner of ruin and disaster for these girls. Yes, Black women have been fired from corporate jobs for wearing cornrows (too ethnic) and for putting a blond streak in their hair at Hooters (Black women don’t have blond hair). But the CEO of Xerox, Ursula Burns, wears a natural, and the real world of corporations has learned to make room for constantly changing expressions of racial and ethnic beauty, even as there is ever-present pushback, attempting to enforce a unitary beauty and hair standard. This twixt and tween is simply called reality.

Black women never really win the hair wars. We keep getting hit by incoming fire from all sides. Today our hair is as much of a conundrum as ever. While Black women spend more on their hair than anyone else, they are routinely less satisfied with results. Weaves, wigs, and extensions are mainstream, from the heads of high school girls to those of TV reality series housewives.

The cultural skirmishes over the significance of Michelle Obama’s hair and her look signifies just how important these questions still are. Just as in the minds of many Whites, there is the image of the “angry” Black man and “angry” Black woman (usually brown to black in skin tone, hands on hips, often but not always full figured), there is also “angry” Black hair. During the 2008 presidential election campaign, when the New Yorker magazine wanted to capture the paranoia that some Whites felt about a possible Obama presidency, the magazine ran a cover that featured Barack Obama dressed as a Muslim cleric and Michelle Obama sporting an Afro, an AK-47 strapped over her shoulders, and a “shut your mouth” glare. While clearly the cover was meant to parody mindless racism, many across the political spectrum took offense.

As first lady, Michelle Obama has been crowned, quite justly, an American queen of style and glamour. She is considered by many ordinary folk, as well as those who are the arbiters of fashion and style, to be beautiful and elegant and a premier symbol of American female beauty, as influential as Jacqueline Kennedy. And her hair, whether it’s bone straight that day, straight but curly, or straight and shiny, has been an endorsement of conventional, acceptable styles. Just as Barack Obama declared that he was president of “all America,” Michelle Obama’s hair has been accepted from sea to shining sea. All but the most hardcore Black cultural nationalists, who long to see a Black woman with an Afro in the White House, or White racists who have in internet chat rooms called the first lady and her daughters “gorillas,” agree that the first lady is the one Black woman in America who has won the hair wars. And beyond the question of hair, who would have imagined a beautiful brown-skinned, identifiably Black woman as the nation’s first lady? OK, the revolution just got televised.

Yet the controversy continues generation after generation. The cultural tumult is inspired, I feel, by the questions that continually haunt Black people. Questions that years of activism, protest, and progress have failed to answer in ways we can uniformly accept: Who are we? What makes us “authentic” Black people? What is our standard of beauty, and where are the roots of that beauty to be found? We can’t agree on the answers, and we both accept and reject the conclusions forced on us by the larger White society. These questions spring from our position as both central to American culture and perennially marginalized by it.

And there are the other questions that hair leads to as well, about femininity, questions that haunt women of all shades, hues, and races. Why do we have to live under the tyranny of a global doctrine that posits femininity in the length and straightness of a woman’s hair? Especially when real beauty, the kind that can light up a room literally and figuratively, radiates from within? Black women, like women all over the world, live imprisoned by a cultural belief system about beauty and hair whose time should have passed.

Today my natural is full of gray hairs, and I love it and my face more than ever, as the battle about Black hair rages on. I often wonder if, with my college degree, my status as a published author and educator who has worn natural hair for over forty years, I am too dismissive and critical of the reasons why so many Black women care so deeply about the state of their hair. I care about my hair too and have frankly chosen the natural as a form of adornment and statement.

But as I said, if you are a Black woman, hair is serious business. My hairphobic sisters have gotten the same message that I received relentlessly as a young girl: my natural hair is bad and it could exact a potentially high price if I choose to expose it and exult in it. I have just always been willing to pay the price. But my sisters know that with straight hair they are acceptable in the corporate world. They see high-profile celebrities like Beyoncé disguise her natural hair with a head full of synthetic hair and rule the world. They have lost jobs because they chose to wear braids. They know that many Black men prefer long, straight hair, and they don’t care what Black women do to get it.

Yet I am deeply conflicted as I assess the young Black girl making minimum wage at McDonald’s, sporting a weave that could easily cost thousands of dollars a year to maintain, money that, yes, I dare to say, she could use to go to college. Certainly a college degree would have a more positive long-term impact on her career goals than a weave. I am conflicted as well by the sight of a Black female professional wearing a wig whose locks reach the middle of her back. All of this is squishy, squirmy, and very difficult to write and speak out loud, for I am violating the racial rules about not airing dirty linen in public and the rule that says sisterhood trumps truths that may be hard to handle. I feel narrow minded and judgmental, when all I really want is a world where Black women are healthy and have healthy hair that does not put them in the poorhouse, cause health problems, or reinforce the idea that they have to look White to be valued. And this does not mean that I want a world of Black women who have hair that only looks like mine.

Yet who I am to judge? Who am I to assume that women who invest hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars in synthetic hair don’t or can’t have as much racial pride as I do? Maybe they know something I don’t, that what’s on your head is not necessarily a barometer of what is in your mind. I know that Black women make these hair choices for reasons beyond reflexive conformity to White beauty standards, reasons such as convenience and the practical need to “fit in” to a prevailing White standard of beauty for the sake of their careers. I know that Black women are damned no matter what we do to our hair. And we are damned, ironically and most cruelly, by our own people, who are not often the ones who hire and fire, but are the ones who accept us into or push us out of the tribe. But I know too how deeply the wounds of racism and self-hatred have burrowed into the souls of Black men and women. I still hear too many Black women, and Black girls of all ages, talk obsessively among themselves, on the internet, in social media, and face-to-face, about their desire for “good hair” and how much they fear having “bad hair.” I am still waiting for that conversation to cease. I have been waiting all my life.