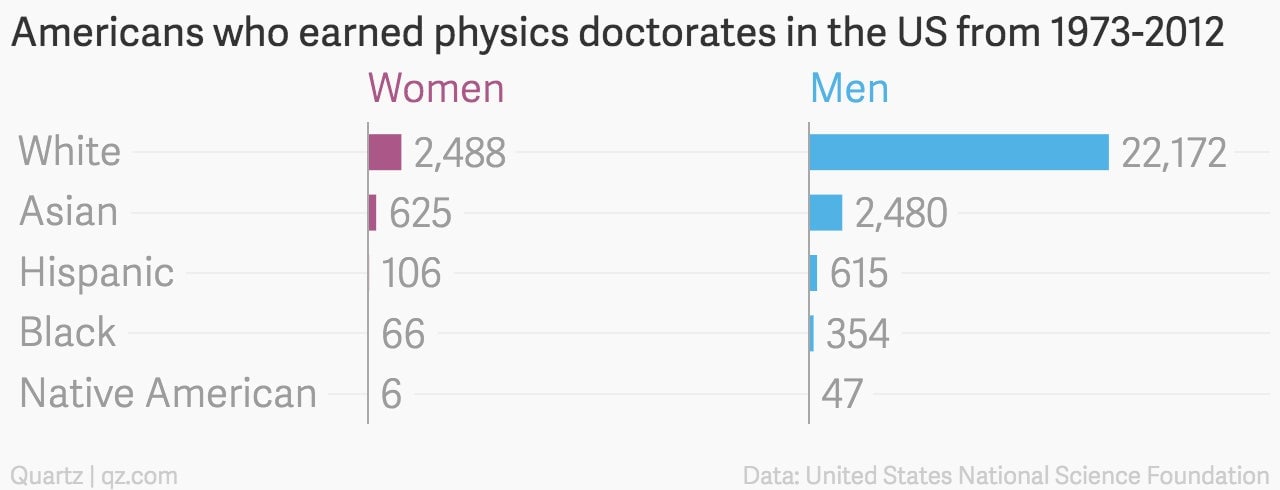

In 39 years, US physics doctorates went to 66 black women—and 22,000 white men

From 1973 until 2012, a total of 66 black American women earned physics doctorates—mostly PhD’s—in US colleges. During that same amount of time, 22,172 white men earned their doctorates.

From 1973 until 2012, a total of 66 black American women earned physics doctorates—mostly PhD’s—in US colleges. During that same amount of time, 22,172 white men earned their doctorates.

These totals only include US citizens or permanent residents who earned their doctorates in the US, not Americans who received a PhD from another country or international students in the US. The vast majority—97.9%—earned PhD’s, though a small number earned other kinds of doctorates, like education.

The double minority problem

There are a lot of reasons why the numbers are so low for women of color, particularly for black, Hispanic, and Native American women.

Girls are often pushed away from math and science at a young age, and people of color, especially black and Hispanic students, have fewer resources than white students to get into college in the first place, let alone excel in the sciences. Once they reach the college or doctorate level, these biases continue.

LaNell Williams graduated with a bachelors in physics from Wesleyan University in 2015, and will start a masters/PhD bridge program in the fall. As a physics student from a middle class Memphis background, Williams told Quartz it’s hard for her to fully relate to many of her peers. While upper class white women can’t understand her experience as a middle class black student, men of color can’t understand the sexism she faces.

“It was hard … to find study groups, it was hard for me to keep up with my work with the lack of preparation and also it was hard for me to find a community.”

Put even more simply: “It was hard, especially as a woman of color, to sit in my classes and not have anyone look like me.”

Power in numbers

That’s a sentiment Jami Valentine can relate to. Valentine remembers what it felt like studying for her PhD at Johns Hopkins University in the early 2000s. “Physics grad school is very daunting,” she tells Quartz. “I just didn’t want to feel so isolated.”

Valentine started looking up female African American physicists, and seeking them out at conventions. Eventually, she and another physicist started keeping an informal count through their website, African American Women in Physics. The website is designed to be a resource for women who are in grad school or getting their bachelors, a way to show that there are other black women in the US who have succeeded in physics, and that they can too.

By their count, updated on June 19, there are at least 83 African American women in the US with physics PhD’s. This includes at least one woman who earned her degree from Canada but works in an American university now (she wouldn’t be included in the an official government count) and 14 who received their doctorates after 2012. Each time a story runs mentioning the website, more women come forward, Valentine says.

There are many benefits to being part of a community who expects you to succeed. Luz Martinez-Miranda is the president of the National Society of Hispanic Physicists, another underrepresented group in STEM. Martinez-Miranda, who grew up in Puerto Rico but earned her doctorate from MIT, says she actually felt more supported than some of her Hispanic Americans peers who grew up as minorities in their communities. “There was more support for my decision to do physics back home than in the United States,” she tells Quartz.

That’s because in Puerto Rico, the majority of people are Hispanic, and there are Hispanics visible in every profession, she noted. This means she did not have to deal with the all of preconceived notions and stereotypes prevalent in the US. Now she encourages Hispanic women to work with her during the summer, both so they can learn and become comfortable with physics, and so they can see that success is possible.

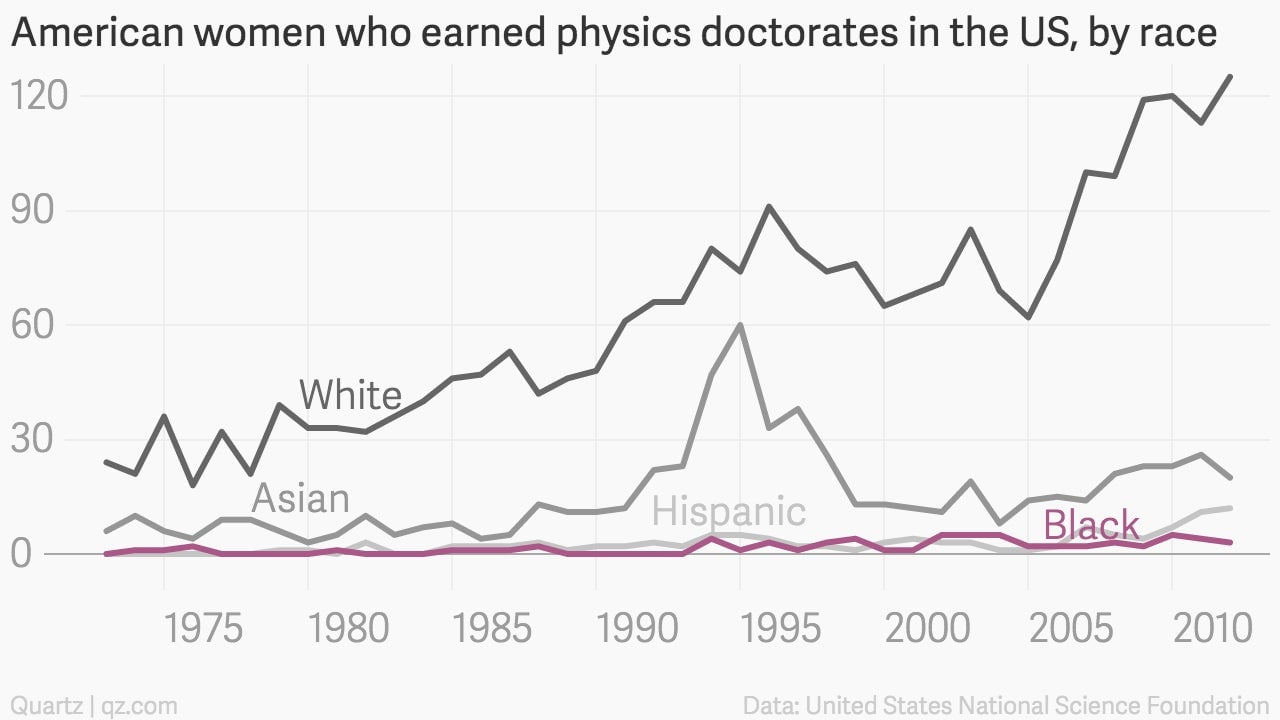

The good news is that while the number of black women with physics doctorates has remained largely stagnant over the last two decades, it has increased marginally since the 1990s—it is no longer common to see a year with 0 black women earning physics doctorates, for example.

Plus, there are now highly successful African American physicists to look up to, something that is already creating positive ripple effects for young women of color, Valentine says. As an example, Valentine points to Jedidah Isler, an astrophysicist whose recent Ted Talk has already been viewed more than 36,000 on YouTube.