An Iranian graphic novelist updates a classic WWII guide for migrants

When my mother picked up a weathered copy of George Mikes’ 1946 classic novel How to be an Alien from a used bookstore in Chicago, she was unimpressed. It was the late ‘80s, and my family had just immigrated to the United States from the Soviet Union. Mikes’ satirically illustrated guide for Eastern European refugees adjusting to life in the West seemed a fitting read: “I have been an alien all my life. Only during the first 26 years of my life I was not aware of this plain fact. I was living in my own country, a country full of aliens, and I noticed nothing particular or irregular about myself; then I came to England, and you can imagine my painful surprise,” Mikes writes. “A criminal may improve and become a decent member of society. A foreigner cannot improve. Once a foreigner, always a foreigner.”

When my mother picked up a weathered copy of George Mikes’ 1946 classic novel How to be an Alien from a used bookstore in Chicago, she was unimpressed. It was the late ‘80s, and my family had just immigrated to the United States from the Soviet Union. Mikes’ satirically illustrated guide for Eastern European refugees adjusting to life in the West seemed a fitting read: “I have been an alien all my life. Only during the first 26 years of my life I was not aware of this plain fact. I was living in my own country, a country full of aliens, and I noticed nothing particular or irregular about myself; then I came to England, and you can imagine my painful surprise,” Mikes writes. “A criminal may improve and become a decent member of society. A foreigner cannot improve. Once a foreigner, always a foreigner.”

Mikes wrily illustrates the uncomfortable truths about the condition of being an outsider. But what was true for him, a post-war Hungarian immigrant to England, was only partially true for my mother and tens of thousands of Soviet immigrants who ventured West forty years later. She felt she could write her own, updated guide to being a refugee. Meanwhile, How to be an Alien was reprinted over 30 times, passing hands among new immigrants to America and the UK, who, like my mother, took its morsels of sardonic advice seriously.

Since then, the narrative of immigration to the West has changed. Hundreds of thousands of refugees from Northern Africa and the Middle East are flooding into Europe, setting out on treacherous voyages across the Mediterranean in the hopes of securing asylum in the EU. In 2014, over 170,000 immigrants arrived in Italy alone, and thousands perish along the way. Those who do make it into “Fortress Europe” are often subjected to harsh, discriminatory treatment.

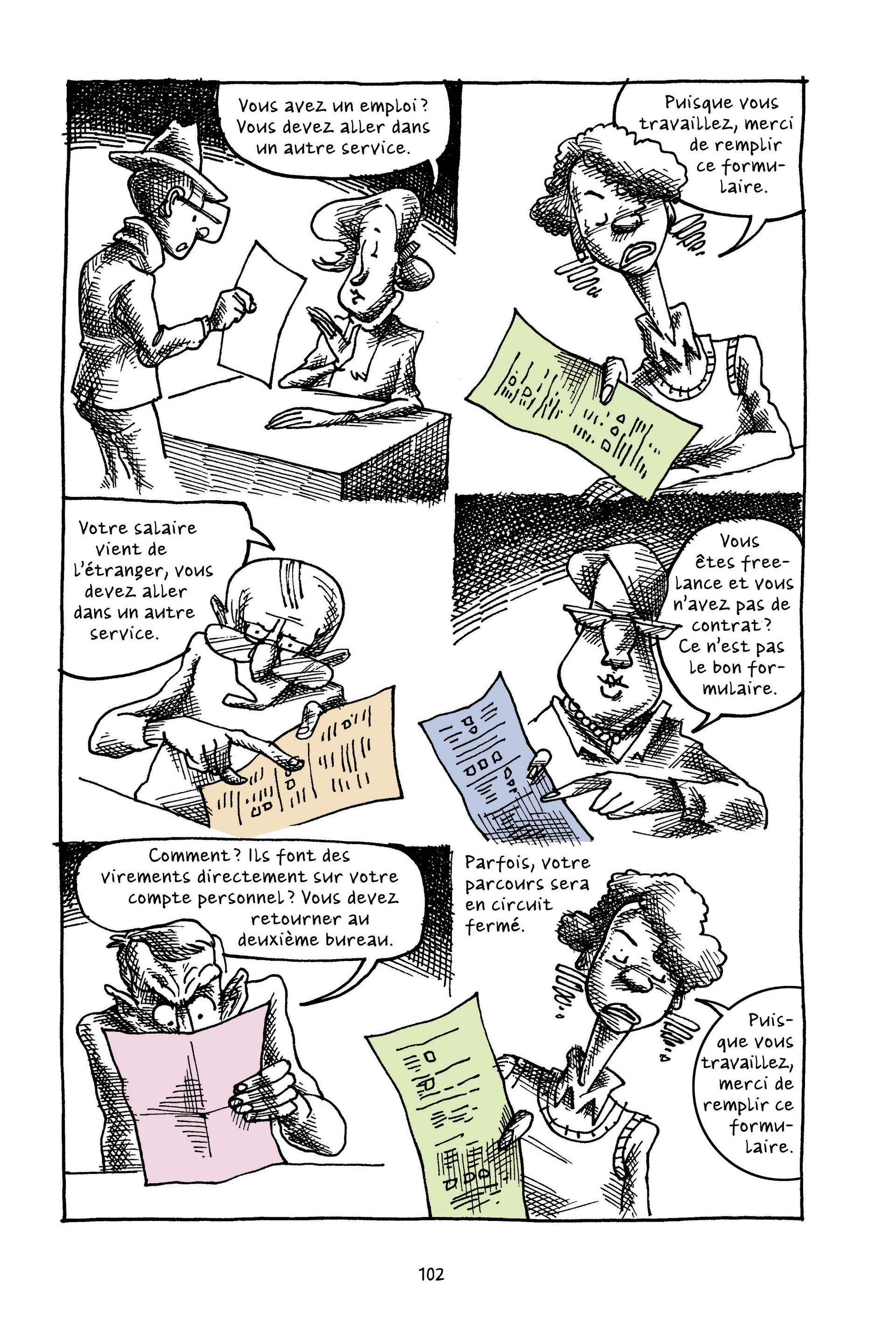

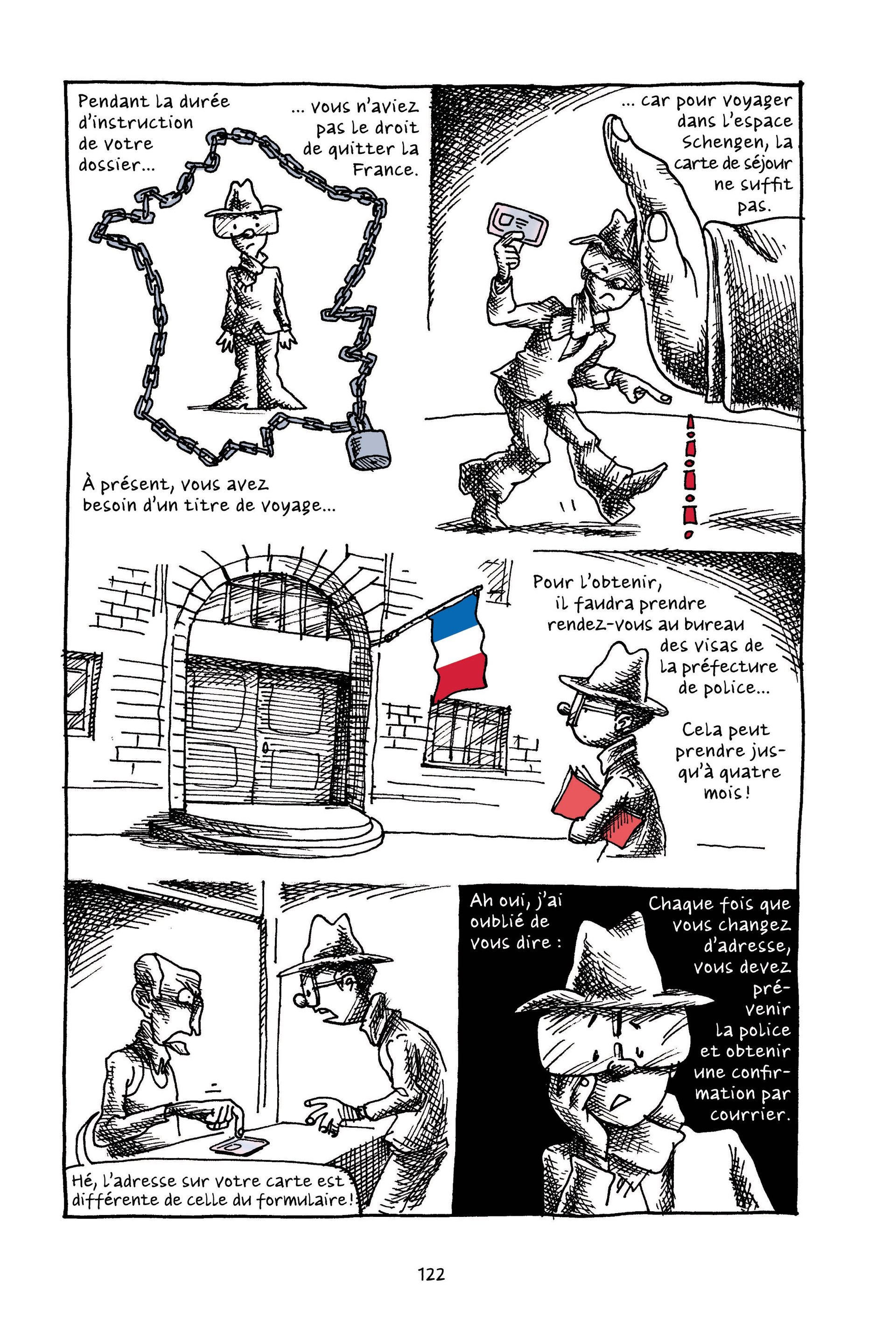

Mikes’ guide, from half a century ago, hardly applies. So Iranian graphic novelist Mana Neyestani wrote a new one, Petit manuel to parfait réfugié politique (“A short guide to being the perfect political refugee,” Cà et Là Editions, 2015), about his experience applying for political asylum in France, a world apart from his former life in Iran—“much less violent, but just as Kafkaesque,” he writes. In 2006, Neyestani was imprisoned in Iran for one of his cartoons, an experience he captures in his first graphic novel, An Iranian Metamorphosis (Uncivilized Books). Six years later, he won his petition to reside in France as a political refugee, but it wasn’t easy.

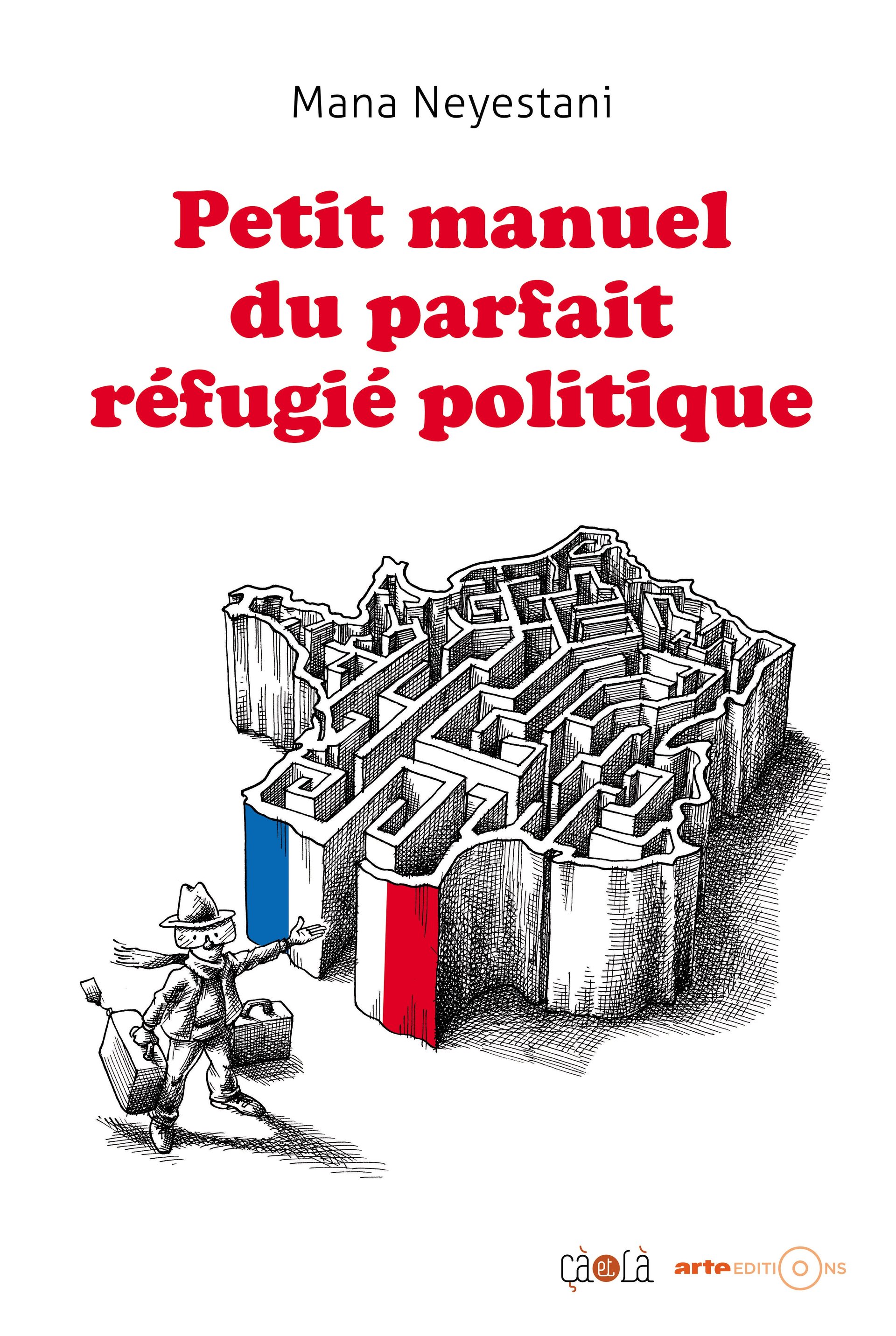

While Mikes’ guide is a cultural primer above all, Neyestani’s “manual” is written as an advice book for immigrants seeking asylum in the European Union. “Before beginning your efforts, know that you must respect the law. What does the law say? The law is a person seated behind a desk who holds your future in his hands,” he writes, illustrating the bureaucratic mountain refugees must navigate, often in a language they do not speak.

The Paris of tourists and catwalks is nowhere to be found in Neyestani’s petit manuel. “Paris is magnificent, Paris is romantic. It’s the city where you can take long walks past cafés, gazing amazedly upon cultural and historic attractions,” he writes. “But if you are a refugee, that does not concern you. You’ll walk down the somber alleys leading to the Office of Refugees.”

Seventy years ago, the main concern of the political refugees Mikes addresses in How to be an Alien was how to blend into western society after being granted asylum. His chapters include “How to be rude,” “How not to be clever,” and “The national passion” (queueing). “The verb to naturalise clearly proves what the British think of you. Before you are admitted to British citizenship you are not even considered a natural human being,” Mikes writes. “If you are tired of not being provided by nature, not being physically existing and being miraculous and conventional at the same time, apply for British citizenship. Roughly speaking, there are two possibilities: it will be granted to you, or not.“ He doesn’t bother going into what happens if the latter.

Today, however, the primary hurdle is getting asylum in the first place, at a time when the EU is visibly struggling to deal with all of the migrants flooding to its shores. Since 2008, 750,000 refugees have been granted asylum in the EU, according to Eurostat. That’s far too many for increasingly euroskeptic publics in the UK, France, and Spain, which is part of the reason why they make it so difficult for asylum seekers to navigate the system.

The often insurmountable obstacles of the European Union’s immigration scheme, and the disparities between member states, emerges from Neyestani’s sarcastic illustrations. He begins the novel with a simple goal: to receive a carte de séjour, an official residency card permitting him to live in France. In order to do so, he must jump through a mountain of hoops: find a fixed address in Paris, with no money to his name; apply to aid organizations for money; wait for hours to register with the authorities before being told he’s filled out the necessary forms wrong; charm immigration officers with just the right tone of voice, without forgetting any key dates in his narrative. One panel half-seriously illustrates how committing a petty crime can be an effective way of securing the high-quality fingerprints necessary for obtaining a permanent residence card. “I lived through all this in 2012,” Neyestani writes, acknowledging that he had it easier than most.

And once Neyestani does receive a coveted carte de séjour, he is introduced to the extent to which French authorities limit the movement of refugees and control their communities. He’s unable to leave France without a special travel document, which takes another two months to procure, and only lasts for two months, before he’ll have to wait five to six months to renew it again. “You will never be able to travel as freely as normal citizens of France, and you will always be surveilled by the police,” Neyestani writes. “The situation may appear similar to the police system in the country you fled. But don’t get me wrong, this time, it’s for your own security.”

“As you may have seen, knowing how to survive in waiting rooms is crucial for your application for asylum. If you have ever experienced solitary confinement, you will be ideally prepared,” Neyestani cautions. “That you were arrested or tortured is secondary, what truly matters is that you perfectly remember precise dates.” It is impossible to imagine similar advice coming from Mikes, and it says something about how the story of immigration has changed that his guide is more preoccupied with how to talk about the weather than how to legally immigrate to a country where there’s nothing else to to talk about but the weather. And besides, refugees landing on European shores are finding that the natives hardly want to talk to them at all.