Studies confirm earthquakes in the midwestern US are caused by the fracking boom

The surge in earthquakes shaking Oklahoma, Texas, and other parts of the nation’s mid-section are likely caused by million of gallons of toxic oil and gas wastewater being disposed of underground, two new studies have found.

The surge in earthquakes shaking Oklahoma, Texas, and other parts of the nation’s mid-section are likely caused by million of gallons of toxic oil and gas wastewater being disposed of underground, two new studies have found.

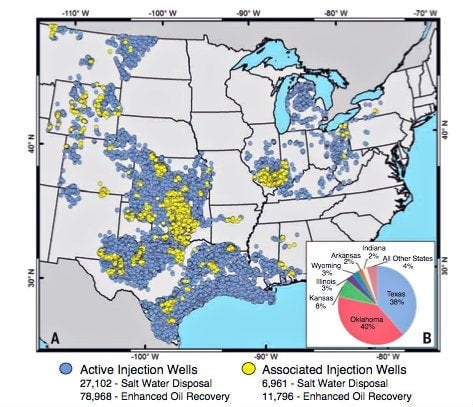

Scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder and the United States Geological Survey analyzed data from earthquakes and more than 106,000 active injection wells across the central and eastern part of the nation—the largest such study to date. They found that “the entire increase in the number of earthquakes in the US midcontinent is associated with injection wells,” according to Matthew Weingarten, a doctoral candidate at the university who led the study.

Weingarten and his colleagues also discovered that wells blasting the most wastewater into the ground, and at a faster rate—more than 300,000 barrels a month—were more likely to be linked to earthquakes. Their research was published Thursday in the journal Science.

Similarly, two geologists at Stanford University discovered that greater seismicity in certain counties in Oklahoma was often preceded by five to 10-fold increases in the volume of wastewater injected. Their findings were published Thursday in the journal Science Advances.

These two papers, the latest in a series of studies on the issue, add to the growing consensus among scientists that the spike in mid-US earthquakes is man-made—and the oil and gas industry is to blame. Conventional oil and gas production has always generated wastewater, but the boom in unconventional fracking, a method to extract previously elusive oil and gas reserves, has led to the production of much more water that needs to be injected below the surface, prompting disposal in seismic-prone areas.

In Oklahoma and Texas, oil production has nearly doubled and tripled, respectively, between 2009—the year when earthquake numbers started escalating—and 2014. For both states, natural gas production also significantly increased during this time.

Energy companies say there’s no proven link between earthquakes and the waste disposal procedures associated with fracked wells.

During the oil and gas production process, drillers produce two main types of wastewater. There’s “flowback,” chemical-laced water used to frack a well, which comes up mostly before production begins. Then there’s “produced water,” the naturally occurring water that flows up a well during production. Both types can end up down a disposal or enhanced oil recovery well.

Not all of this wastewater ends up being injected underground, however. Some states, such as Pennsylvania, might treat the waste and store it in tanks or open-air ponds, or recycle it for use at another drilling site, or use it for other purposes. But in Oklahoma and Texas, injection is a major form of disposal.

Earthquakes of magnitude three or below dominate the recent surge in seismicity. These quakes are barely felt, and rarely cause damage. But there have been a few noteworthy exceptions that scientists believe are likely tied to injection. In 2011, a magnitude-5.6 quake struck Prague, Oklahoma; the damage was mainly limited to cracks in some buildings, collapsed roofs, and items falling off walls. In 2012, a magnitude-4.8 earthquake hit Timpson, Texas, causing some chimneys to collapse and windows to break.

Man-made earthquakes are “controllable” to some extent, said George Choy, a scientist at the US Geological Survey. Since companies aren’t going to stop producing oil and gas soon, there should be a way to handle their wastewater in a safer way, said Choy, who was not involved in either of the new studies.

Oklahoma regulators are already taking action, he said. They’ve closed at least 50 wells and reduced the allowable volumes of injection liquid at more than 150 others. In Texas, regulators are currently investigating whether the activity of two companies has contributed to earthquakes near their operations.

A comprehensive look

The recent investigation by Colorado and US Geological Survey scientists is the first to take a comprehensive look at this issue. They compiled a massive database of publicly available information on the characteristics of all active injection wells in the middle and eastern parts of the country, such as location, monthly injection rate, and wellhead pressures as of December 2014.

Well data was then compared to earthquake data, including quake magnitude and location. This allowed researchers to sort the wells into two categories: those associated with earthquakes (usually within 10 miles of a recent earthquake) and those not associated.

Out of the more than 106,000 wells reviewed, roughly 27,000 fell into the “associated” category. For example, if an earthquake occurred in any area close to multiple wells, they would all be considered “associated.” Moreover, wells close to a single earthquake and wells close to multiple earthquakes would both fall into this category.

With this information at hand, Weingarten and his colleagues ran statistical analyzes searching for patterns between the associated and non-associated well groups in order to answer the simple, critical question: Do wells associated with earthquakes have distinct attributes?

In short, yes. Among all the factors reviewed, researchers found one statistically significant relationship between earthquakes and the amount of waste injected each month. Specifically, the wells with high injection rates are at least 1.5 times more likely to be near an earthquake than a lower-rate well.

One of the paper’s surprising findings has nothing to do with the wastewater disposal wells mentioned above. There’s a different—and more common—type of injection well used for a process called “enhanced oil recovery,” a technique that stimulates an aging production well. Earthquakes are generally triggered when faults move due to a buildup of pressure in the surround rock. At enhanced oil recovery wells, material is injected deep into the earth (adding pressure) and then later pumped back up (decreasing pressure) nearby. It’s hard to build up enough pressure to trigger an earthquake in this process, but not impossible. The study showed that enhanced oil recovery wells accounted for 60% of the earthquake-associated wells, more than previously thought.

A separate study by Stanford scientists more closely investigated six hot spots of seismic and injection activity in Oklahoma. They found that the three areas with the highest injection rates for wastewater disposal also had the most earthquakes. In a different area with high injections in enhanced oil recovery wells, a much smaller number of earthquakes occurred. The remaining two study areas had low levels of injection and fewer earthquakes.

After years of skepticism, in April, the Oklahoma Geological Survey said that the state’s staggering rise in earthquakes “is very likely” triggered by waste-related injecting wells. Before 2009, Oklahoma was struck by fewer than five earthquakes of magnitude 3.0 or higher a year. In 2014, that number jumped to more than 140 earthquakes in the same range of intensity. Last year, Oklahoma surpassed California as the most seismically active of the 48 contiguous states.

Mark Zoback, a Stanford University geophysics professor who co-authored the Oklahoma study, said his findings are “completely in sync with” the state Geological Survey’s announcement.

This post originally appeared at InsideClimate News.