China has a growing “lost generation” of migrant children

Four-year-old Zou Ziyi sat quietly in a shabby classroom while the Walt Disney movie Frozen played on a television set. When the movie ended and the familiar theme song “Let It Go” began, Ziyi looked around at the other kids and seemed to want to say something.

Four-year-old Zou Ziyi sat quietly in a shabby classroom while the Walt Disney movie Frozen played on a television set. When the movie ended and the familiar theme song “Let It Go” began, Ziyi looked around at the other kids and seemed to want to say something.

But he didn’t. He speaks very little, and almost never forms complete sentences, the adults around him say.

“He has been wearing the same suit for a week,” said Wu Xinqin, a housewife who works part-time in a childcare center in Guangzhou. Ziyi’s father, a motorcycle taxi driver who works until midnight every night, has little time for him, and his mother left the family last year. His grandfather Mr. Zou, a 55-year-old migrant worker from Hubei province, takes Ziyi home from childcare.

Ziyi is the child of one of the 20 million-plus migrant workers in Guangdong province, China’s manufacturing heartland. Compared to many left-behind children back in his parent’s hometown of Jingmen, in the Hubei province, he is lucky in some ways—he lives with his father and grandfather.

But like many millions of other migrant children, Ziyi’s life is far from easy. He spends most of the day in a charity childcare center, because the adults in his family have to work 10 hours a day and can’t afford anywhere else.

He is getting no real education from either family or school, and little affection or social interaction. He spends his time alone, watching movies and looking at picture books. Over the course of a week at the childcare center, reporters saw Ziyi say only a few words—“elephant,” “I want that,” and “no.”

A generation sacrificed for growth

For the past several decades, hundreds of millions of Chinese migrant workers have left their rural hometowns and flocked to the big cities, where they can usually find a better-paying job in manufacturing than in farming back home. This migration has been key to China’s economic boom—manufacturing consistently made up about one-third of the nation’s GDP even as the economy grew by 10% a year or more over the past decade.

But the offspring of these workers have had it rough. Some of these kids are in danger of becoming a lost generation in China, one that has been sacrificed to the country’s dramatic economic growth.

Because of the high costs of urban life, many migrant workers leave their children back home—or send them there—to be taken care of by extended family. The plight of China’s “left-behind” kids, as these approximately 60 million children are known, gained national attention after four were fatally poisoned in June in the rural southwest. Officials have promised reform. “Such a tragedy cannot be allowed to happen again,” premier Li Keqiang pledged, and ordered government ministries to step up their supervision of rural kids.

But nearly as many displaced children are growing up in China’s urban centers, where they receive little attention from the government or society. Tens of millions of migrant workers have brought their kids with them to their jobs, and keep them in cities while they work.

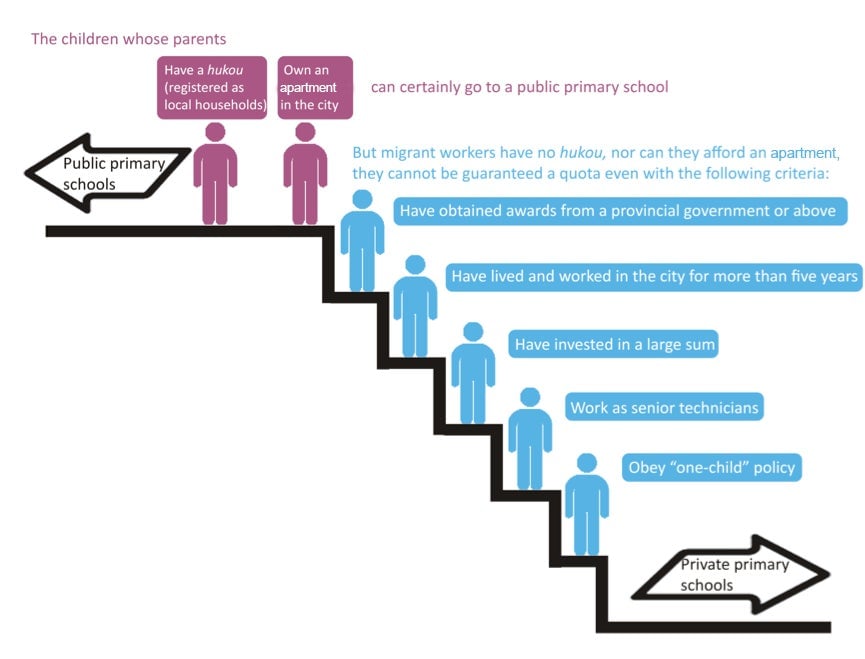

Sometimes called “mobile” or “migrant” children, these kids and their families lack a local community support network, and often they don’t qualify for government schools because of China’s hukou system, a household-registration system that determines the kind of welfare benefits citizens can get. Migrant children who inherit the so-called “rural hukou” from their parents don’t get the same rights as their new urban peers.

These children are forced to go to makeshift, expensive, non-government schools, which often lack adequate teaching, and can focus mainly on making profits. Disconnected from their original communities in rural areas, but without regular attention from a nearby parent, many of these kids are only slowly developing the socialization skills needed to one day become functioning adults.

In some cases, they’re getting a worse education than their parents did a generation ago in rural China.

The problem is huge, and getting worse

The number of migrant children is increasing. In 2010, one out of every four children in China’s urban areas was a migrant child, according to a survey by the United Nations Children’s Fund. In 2013, that proportion rose to one out of three—a total of 35.8 million kids.

Three manufacturing provinces—Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang—accommodate the most migrant children:

Busy parents, lonely kids

Since the one-child policy was introduced in the 1970s, Chinese kids have been mostly brought up by a collective effort—their parents, together with four grandparents, take turns looking after them. (Some call this the 4-2-1 family structure, for four grandparents, two parents, one child.) Ideally, when migrant workers head to cities and leave their children behind, the extended family that stays behind babysits. When kids migrate with their parents to big cities, that system falls apart.

Thanks to long working hours of 60 hours a week or more, migrant parents usually have little time to communicate with their children, even though their initial motive for bringing children with them is to have more interaction with their kids.

Ziyi’s father drives a motorcycle taxi at night. Mr. Zou, his grandfather, brings Ziyi to the childcare center before heading to work himself at about 8am, transporting construction materials by tricycle in a gritty market for 15 yuan (about $2.40) per delivery. He works more than 10 hours a day, six days a week. He does not send Ziyi to a kindergarten, he said, because the kindergartens are closed in early afternoon (and do not open on Saturdays), which would prevent him from working overtime for extra money.

When Mr. Zou is with Ziyi, they either watch TV or go for a walk around where they live, a collection of low-rise buildings and narrow alleyways called Shigang Village in the southern suburbs of Guangzhou. The family spends nearly 500 yuan ($80) per month on rent and utilities, for two 15-square-meter rooms with no hot water and a bathroom and kitchen they share with other families. But that doesn’t mean they have formed close friendships with anyone. “We rarely talk to the locals here,” Mr. Zou said.

On one side of the road is the jam-packed, shabby neighborhood where migrant workers live; on the opposite side are spacious, newly built apartments. Ziyi’s family’s landlord, who is a local resident in Guangzhou, lives in a newly built apartment just across the street, where units average 1 million yuan ($160,000).

Ziyi’s parents and grandfather moved to the area more than a decade ago. His mother left two years ago, and hasn’t been heard from since. Ziyi has never seen the zoo, although his grandfather knows the little boy is obsessed with animals. Mr. Zou doesn’t have time to bring him.

Instead, Ziyi spends most of his time at a childcare center in the village.

The two-floor center has a big classroom with books and a large television set on the ground floor, and a dining room and a kitchen. Next door is a railway ticket office where migrant workers queue up as early as 4am to get a ticket back home during the Chinese New Year. On any given morning, as many as 20 children will be dropped off at the center, where they spend most of the day singing karaoke and watching cartoons.

There is only one full-time minder to watch the children, aided by a handful of part-time volunteers. They teach the children some basic reading and writing, and also other things like music and nature, but not in a systematic way.

Here are a few moments in Ziyi’s day:

Socialization suffers

Language isn’t the only thing these kids have not learned sufficiently.

Six-year-old Song Yingying comes to the center regularly, and is much more lively and active than other girls, making her often stand out from the crowd.

Teachers say she also does not know the right place to use the toilet, because her busy parents have never taught her. She sometimes relieves herself in the center of a yard near the center.

Her mother, Ms. Lu, said in an interview that she came to Guangzhou in 2003 from Jiangxi province. She also has a son, Song Ruyi, who is four years older than Yingying.

Ruyi was born in Guangzhou and sent back to Jiangxi when he was three months old. He was brought up by his grandparents, who spoilt him so much, his mother said, that he became a very naughty boy. When he started primary school there, he fought with his classmates frequently, and Ms. Lu was forced to bring him to Guangzhou.

Children always want to grow up with their parents, Ms. Lu said she realized after Ruyi came to live with her, so she brought Yingying to live with her when she turned two. “People did not make much money in the past. Nowadays our income has gone up a bit. Sometimes if economy goes good, one month’s salary can cover the tuition fee for half a year,” she said.

But Lu and her husband work in a construction crew whose work schedule is irregular. Sometimes they are extremely busy for months, and have little time for the little ones. “In the evening when we come back late, the elder one is doing his assignment, and the younger one is just playing by herself,” she said.

Getting a good education is tough for migrant kids

Another reason that China risks raising a lost generation is because migrant children have limited access to decent schooling. In Guangzhou, primary schools are divided into two types: the better public ones and the largely unregulated private ones. The primary school system always favors local kids, and puts up huge hurdles for non-local parents:

There are 117 public primary schools and 24 public middle schools in Guangzhou’s Panyu district, according to Guangzhou Daily. Starting from this year, the number of non-local students taken by public primary schools cannot exceed 10% of all newcomers each year, according to the district’s education bureau.

Meanwhile, parents describe the area’s private primary schools as incompetent and corrupt. Mrs. Jiang, from Sichuan province, has a seven-year-old daughter at one that asks the pupils to do the final exam before the exam date, so that they know the questions beforehand and can artificially inflate their test scores, she told reporters.

Of the over 20 children who come to the childcare center, only two go to a public school, said Zhao Kaiqiong, the center’s only full-time child minder. Even though they are public, parents pay as much as $4,800—nearly their entire annual income—as an entry fee. Even that huge sum, which is paid to school administrators, isn’t enough—parents also need guanxi, or social connections, to get their kids into a government school.

A million migrant kids are not going to school at all

Zhao said she has worked with dozens of migrant children since the center was established nearly two years ago. “The government should relax the restrictions of access to public schools, making it more equal for local and non-local students,” she said.

She grew up as a left-behind child herself, and understands the sorrow of not being with your parents, so she is dedicated to her job as a babysitter for migrant children. There are few centers like this one, she said—she knows of only one other in Guangzhou.

If parents fail to get their kids into public schools, and they aren’t happy with the private ones, they have no choice but to send their children back to their original hometowns. But the kids aren’t happy about it.

Eight-year-old Shi Ge, from Henan province, was born in Guangzhou to migrant parents but sent back home. She stayed in Henan until the age of five and moved to Guangzhou to reunite with her parents. She shook her head back and forth when asked if she wanted to go back to Henan. “I am afraid of being sent to my aunt’s in Henan,” she said. There, she added, “nobody cares for me.”

Follow writer Coco Feng at @CocoF1026.

Additional reporting by Jane Li.