What the hell has happened to the price of ground beef?

As Americans get ready to fire up the grill for the Fourth of July weekend, they might hop in their SUVs, park at the nearest big box store, roll a massive shopping cart through a wide aisle towards the meat case, compare the prices of packaged beef on display, and in the vein of Clara Peller, exclaim, “Where’s the cheap beef?”

As Americans get ready to fire up the grill for the Fourth of July weekend, they might hop in their SUVs, park at the nearest big box store, roll a massive shopping cart through a wide aisle towards the meat case, compare the prices of packaged beef on display, and in the vein of Clara Peller, exclaim, “Where’s the cheap beef?”

Ground beef prices have been soaring for five years. Droughts have wracked Texas, California and other cattle-producing plots of land. Prices began spiking in earnest in late-2012. In December 2012, the price of a pound of 100% ground beef was $3.08. It jumped 10.6% that month, and by May 2015, a pound cost $4.14, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“Hamburger is the new steak,” says David “Rev” Ciancio, director of marketing for New Jersey-based Schweid & Sons, which sells ground beef to Five Guys, Fatburger and other chains. “Steak is the new Mazeratti.”

What the hell happened? And why is no relief in sight?

Even the droughts are bigger in Texas

To begin at the beginning: In October 2010, the rain stopped in Texas. No rain meant less grass for grazing cattle meant ranchers fed herds with hay and other expensive feed.

As the drought wore on, Alan Newport, the editor of industry trade magazine Beef Producer, sat in Oklahoma and watched trucks loaded with hay headed south on I-35 to parched Texas ranches and cattle loaded onto potbelly trailers headed north, bound for grazing land in still-verdant North Dakota.

“That’s an expensive way to try to get through a drought,” he says.

Dry conditions doubled hay prices during the drought, further straining ranchers, who were forced to cull their herds – that is, send heifers to the chopping block rather than breed them – and sold others out-of-state.

While prices soared, supply was actually shrinking. By January 2014, the USDA announced that the nation’s cattle herd had shrank to 87.7 million head, the lowest figure since 1951.

In May, Texas’s unending drought ended. Drenching rain in Texas–following a wet winter and early spring–left just 15% of the state still experiencing moderate to severe drought conditions, the lowest percentage since the drought began, according to the US Drought Monitor. Reservoirs filled up, farmland was quenched and Texas rivers rose.

But even with the drought over in Texas, high beef prices are likely to endure for at least another year, industry observers say, and likely more.

Rebuilding the herd will be a years-long process, Newport says. It’s a matter of arithmetic. Angus cows have a gestation period of 283 days, compared to sows (114 days) and hens (21 days). A cow can birth one or two calves a year, far less than sows (20 piglets) and chicken (200 to 300 chicks). In the short term, ground beef prices may actually get worse, as ranchers hold back heifers for birthing.

Meanwhile, California–the fourth largest producer of cattle with 5.2 million head–remains parched. Grass is in such short supply that ranchers in the state’s Point Reyes National Seashore are lobbying park officials to fence in tule elk to keep them from competing for grazing land.

And while Texas celebrates its good fortune, it might recall January 2010. That month, a year-and-a-half-long drought–the worst in 50 years – finally ended.

“The back of the drought is broken,” the state’s climatologist told the New York Times.

Nine months later the next dry spell began.

Hamburger is the new steak. (And that’s bad.)

Drought is the primary cause of ground beef price spikes, but the hamburger has also been a victim of its own success.

How popular are burgers? Travel to the New Jersey wetlands. There, in the shadow of the Meadowlands, tractor-trailers queue up every morning, waiting to dock with one of Schweid & Sons’ three delivery bays. Some are dropping off combos–massive cardboard bins that can hold 2,000 pounds of muscle. Other trucks are picking up finished product: ground beef knitted into loaves, injected into bags and carved into patties. If you ate at a Five Guys, FatBurger, Fuddruckers or Cheesecake Factory east of the Mississippi this year, your burger morphed from muscle into “meat spaghetti” in the company’s massive refrigerated facility.

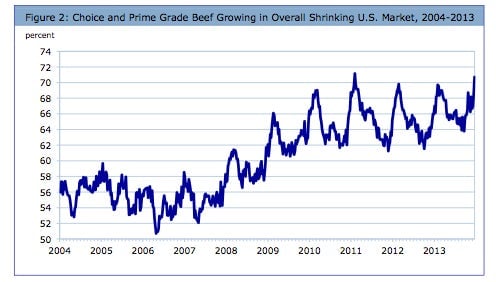

Schweid & Sons is riding the wave of national interest in gourmet hamburgers–part of a tectonic shift in America’s beef consumption that has seen beef in general–and steak in particular – fall from favor as prices rise, budgets shrink and health concerns predominate. Those that are still eating red meat are increasingly eating burgers. But hamburger’s victory may be a Pyrrhic one: the demise of high-margin steak is bad news for ground beef prices, industry analysts say.

Beef and veal consumption have been in decline for the past 30 years.

But ground beef continues to gain market share.

In his gastro-history The Hamburger, food critic Josh Ozersky traced the burger’s rise to respectability to the “Haute Burger Skirmish of 2003,” when French chef Daniel Boulud and steakhouse chain Old Homestead jockeyed to offer ever more extravagant hamburgers – foie-gras- and short-rib-stuffed burgers, Kobe beef burgers, burgers topped with shaved Périgord truffles.

“These dishes,” he wrote in the 2008 book, “could be considered an anomaly but for the way they were immediately, and successfully, emulated by a dozen other New York restaurants.”

Hamburgers gained momentum during the Great Recession, as expense accounts shrank and diners began chucking $50 steaks for $20 burgers. Better-burger chains like Five Guys and Shake Shack have also driven ground beef mania.

“When the economy slows down, my dad used to say that it’s great for the burger business,” says Jamie Schweid, executive vice president at his family’s company. “It’s the only affordable beef product–thankfully–out there.”

And yet Schweid & Sons is not celebrating steak’s demise. Steak has the highest margins of all meat on a cow, and it acts like a fullback, laying down blocks for burgers–when it is out front and demand is high, ground beef is the beneficiary. When steak doesn’t keep pace–between March 2010 and March 2015, ground beef prices were up 87.5%, compared to 45% for steak–it’s not good.

“You don’t raise animals for ground beef,” Schweid says. “We want middle meats to be in demand.”

For the last 20 years, cattle have been bred and fed as if steak, rather than ground beef, is surging. The average time on feed for a 750-pound steer was 175 in 2014, up from 151 days in 1995, according to Professional Cattle Consultants. As soy and corn prices surge, so too has the cost of fattening those cattle.

Is there another way? Perhaps. In a Jan. 2014 paper entitled “Ground Beef Nation,” Don Close, a vice president at Rabobank, argued that the current steak-as-fullback model should be shaken up. He argued that cattle with the least genetic potential to pack on pounds – roughly a third to a half of the herd – ought to be kept grazing longer to save on feed and then harvested at lower weights, yielding more ground beef for less money.

Nevil Speer, an industry consultant and former professor of animal science at Western Kentucky University, disagrees. Ground beef is still just too cheap, he says, and while it represents nearly 60% of total beef volume sold, it represents just 20% of revenue.

Some middle meats are making their way into hamburgers now too. Rounds–hind leg muscles traditionally used for low-quality steaks–have fallen out of favor and are now being tossed into the grinder, Newport says. Brisket too has become a popular muscle for more up-market burger blends. (Brisket prices more than tripled between 2008 and 2014).

But even selling higher-margin burgers–Schweid & Sons has 1,100 different ground beef blends – the company isn’t able to pass along all price increases to customers. When the price of ground beef spikes, and the company starts negotiating with its customers to meet in the middle.

“At those times,” Schweid says, “we have to eat margin as well.”

But another reason burger chains are in the red is that ground beef is no longer in the pink.

The revenge of “pink slime”

In March 2012, 1.2 million head of cattle vanished.

The equivalent of about one percent of the nation’s herd was obliterated not by drought or disease but an icky feeling, a collective national shudder at a product the meat industry calls finely textured beef–affectionately known as “pink slime.”

To recap: in March 2012, the US Department of Agriculture announced that it would begin buying finely textured beef (FTB) for school lunches. The filler had been a cheap and popular component of fast-food chain hamburgers nearly two decades. But food writers dug up a critical 2009 New York Times story highlighting the controversial production methods, ABC News followed with an 11-part series about the producer, and social media networks exploded with photographs–some of them misleading–of “pink slime.” Within weeks, McDonald’s, Burger King and Taco Bell declared the stuff verboten.

At the time, Beef Products Inc., a previously obscure, Dakota Dunes, South Dakota-based processor, and Cargill, the Minnesota-based commodity and food processing multinational and the nation’s largest privately owned corporation, together produced most of the country’s finely textured beef. BPI quickly closed three of its four plants, and the two companies’ combined production had dropped 80%, estimates Mike Martin, Cargill’s director of communications. As drought wracked large swaths of cattle country, more than 600 million pounds of ground beef disappeared from the market.

The price impact wasn’t immediate–ground beef hovered around $3 a pound for most of 2012. But with a national herd of 89.8 million head of cattle, the equivalent of 1.2 million cows disappearing is significant.

“A one percent shift either way can make a huge difference in price for any given commodity,” Newport says.

Anti-pink slime crusaders marched under two banners:

- Industrial processes have hijacked our food system, and,

- this stuff is gross.

The process is certainly industrial. In the 1990s, Cargill and Beef Products Inc. separately developed and patented technology to convert carcass scraps into lean meat, rather than relegating it to cooking oil and pet food. With Cargill’s method, beef trim is placed in stainless steel tanks and warmed to 100 degrees, then moved to centrifuges, where the tallow separates into small pellets. BPI then treats the product with ammonia to kill E. coli and salmonella, which are more common in finely textured beef than higher grades of meat.*

(Bettina Elias Siegel has moved on to other pastures: she declined to be interviewed for this story. Her website continues to tout her victory over FTB.)

Gross or not, the process lets Cargill harvest an extra 25 pounds of lean meat from each cow. The industry has tried to channel the nose-to-tail, whole animal movement: if you care about the environment, you should support squeezing every ounce of protein from this land-intensive ruminant as possible.

High ground beef prices are forcing pink slime back onto dinner plates, says Mary Chapman, a senior director at Technomic, a Chicago-based consulting firm focused on the foodservice industry.

“[They’re using] the lowest cost beef products,” she says. “They’re using everything that they can.”

Martin says Cargill is at 60% production capacity, up from 20% after the media storm. Beef Products Inc. has reopened a collection facility but is still under 50% capacity.

But the media furor has both companies wary of crowing about a comeback. Cargill says it has more than 400 customers buying finely textured beef, but the company won’t disclose their names except to say that most FTB is headed for processed foods like canned chili and frozen TV dinners, rather than fresh beef, as it did before. (If you want to put Martin at ease and get him talking, it helps to put “pink slime” in towering air quotes once and call it “FTB” from thereon out.)

Beef Products Inc., meanwhile, is locked in a $1.2 billion defamation lawsuit against ABC News, with the suit currently in fact discovery. The North Dakota company has also hired Edelman, the global public relations giant, to handle its media relations.

The invisible hand can’t stop feeding us burgers

When prices go up, demand goes down. It’s a central tenet of capitalism. Even time-honored American pastimes like driving are subject to this logic: when gas goes up, driving goes down.

And yet as ground beef prices reach new heights, Americans are eating more hamburgers than ever before. Why?

Part of the story: consumers don’t realize that prices are high. Just 47% of American consumers are even aware that beef has gotten more expensive, according to a recent poll by Beef & Pork Consumer Trend Report. Less than a quarter of consumers have changed their consumption habits at all.

The misperception partly stems from retail prices: grocery stores and burger chains are wary of passing along too much of the price increase to consumers. But unlike gas prices, which are broadcast in big black letters at every gas station, diners don’t see how the burger is made–or how much it costs. McDonald’s double-cheeseburger still costs a dollar. Andrew Zurica, who owns the burger truck Hard Times Sundaes in Brooklyn, has increased his prices from $4.50 for a burger without cheese to $5 with or without cheese, a change few customers have noticed.

“I’ve been watching the price waiting for it to go down,” he says. “I haven’t called anybody to break chops. You have to take it on the chin.”

Chains are pushing alternatives: chicken sales grew three percent to $5.4 billion in the first quarter of 2015, compared to a one percent increase to $7.9 billion for burgers, according to the market research firm NPD Group.

But beef is still on the menu. Despite being hammered by high beef prices, chains are under pressure to unveil new offerings and keep up with competitors, says Emily Balsamo, a research analyst at Euromonitor International. Among new dishes she has tracked: the “Mega Meat Stacks” sandwich at Arby’s, a bun-less “Thinburger” at Fatburger (a knockoff of KFC’s Double Down sandwich), and a chicken-fried steak platter at Church’s Chicken.

That war of attrition has been a drag on McDonald’s and other chains.

“It’s bad,” Balsamo says. “They’re calling it the ‘lost year’ if you listen to these earnings calls.”

Chew on.

We welcome your comments at [email protected].

*Correction: This article originally stated that both BPI and Cargill use ammonia to create lean mean from carcass scraps. Cargill does not use ammonia. The sentence has been corrected.