The death of Aaron Swartz is the failure of brinksmanship—and prosecution of real computer crimes

Reality is what refuses to go away when you stop believing in it.

Reality is what refuses to go away when you stop believing in it.

The reality—the ground truth—is that Aaron Swartz is dead.

Now what?

Brinksmanship is a terrible game, that all too many systems evolve towards. The suicide of Aaron Swartz is an awful outcome, an unfair outcome, a radically out of proportion outcome. As in all negotiations to the brink, it represents a scenario in which all parties lose.

Aaron Swartz lost. He paid with his life. This is no victory for US Attorney Carmen Ortiz, or Steve Heymann, or JSTOR, or MIT, or the United States government, or society in general. In brinksmanship, everybody loses.

Suicide is a horrendous act and an even worse threat. But let us not pretend that a set of charges covering the majority of Aaron’s productive years is not also fundamentally noxious, with ultimately a deeply similar outcome. Carmen Ortiz and, presumably, Steve Heymann are almost certainly telling the truth when they say that they had no intention of demanding 30 years of imprisonment from Aaron. This did not stop them from in fact, demanding 30 years of imprisonment from Aaron.

Brinksmanship. It’s just negotiation. Nothing personal.

Let’s return to ground truth. MIT was a mostly open network, and the content “stolen” by Aaron was itself mostly open. You can make whatever legalistic argument you like; the reality is there simply wasn’t much offense taken to Aaron’s actions. He wasn’t stealing credit card numbers, he wasn’t reading personal or professional emails, he wasn’t extracting design documents or military secrets. These were academic papers he was “liberating.”

What he was, was easy to find.

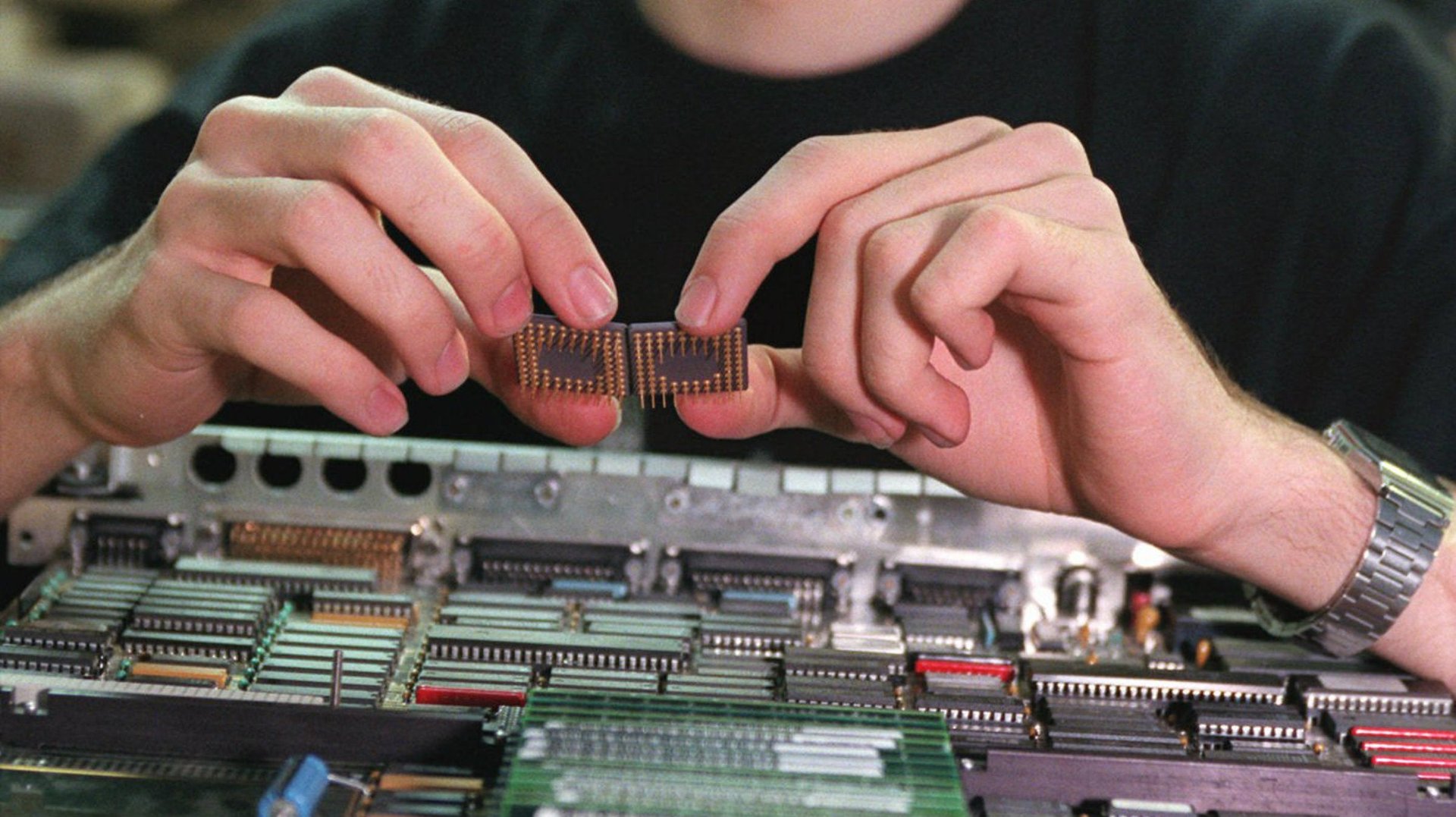

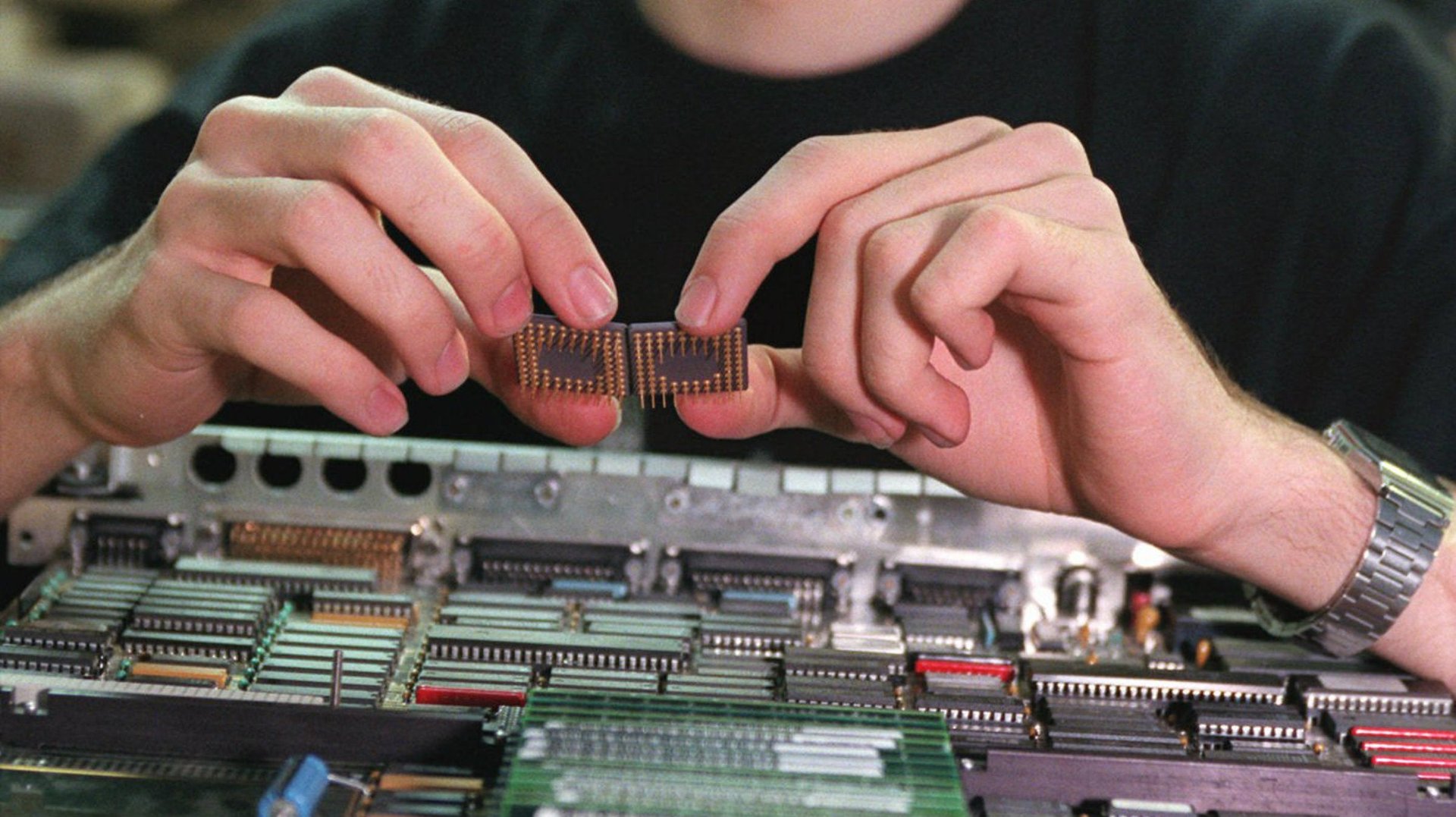

I have been saying, for some time now, that we have three problems in computer security. First, we can’t authenticate. Second, we can’t write secure code. Third, we can’t bust the bad guys. What we’ve experienced here, is a failure of the third category. Computer crime exists. Somebody caused a huge amount of damage—and made a lot of money—with a Java exploit, and is going to get away with it. That’s hard to accept. Some of our rage from this ground truth is sublimated by blaming Oracle. But some of it turns into pressure on prosecutors, to find somebody, anybody, who can be made an example of.

There are two arguments to be made now. Perhaps prosecution by example is immoral—people should only be punished for their own crimes. In that case, these crimes just weren’t offensive enough for the resources proposed (prison isn’t free for society). Or perhaps prosecution by example is how the system works, don’t be naïve—well then.

Aaron Swartz’s antics were absolutely annoying to somebody at MIT and somebody at JSTOR. (Apparently someone at PACER as well.) That’s not good, but that’s not enough. Nobody who we actually have significant consensus for prosecuting models himself after Aaron Swartz and thinks, “Man, if they go after him, they might go after me.”

The hard truth is that this should have gone away, quietly, ages ago. Aaron should have received a restraining order to avoid MIT, or perhaps some sort of fine. Instead, we have a death. There will be consequences to that—should or should not doesn’t exist here, it is simply a statement of fact. Reality is what refuses to go away, and this is the path by which brinksmanship is disincentivized.

My take on the situation is that we need a higher class of computer crime prosecution. We, the computer community in general, must engage at a higher level—both in terms of legislation that captures our mores (and funds actual investigations—those things ain’t free!), and operational support that can provide a critical check on who is or isn’t punished for their deeds. Aaron’s Law is an excellent start, and I support it strongly, but it excludes faux law rather than including reasoned policy. We can do more. I will do more.

The status quo is not sustainable, and has cost us a good friend. It’s so out of control, so desperate to find somebody—anybody!—to take the fall for unpunished computer crime, that it’s almost entirely become about the raw mechanics of being able to locate and arrest the individual instead of about their actual actions.

Aaron Swartz should be alive today. Carmen Ortiz and Steve Heymann should have been prosecuting somebody else. They certainly should not have been applying a 60x multiple between the amount of time they wanted, and the degree of threat they were issuing. The system, in all of its brinksmanship, has failed. It falls on us, all of us, to fix it.