For real maker culture, try a global gathering of radio hobbyists

The last weekend of June, more than 17,000 people from around the world gathered in Friedrichshafen, Germany, to tune into a seemingly outmoded technology: the radio.

The last weekend of June, more than 17,000 people from around the world gathered in Friedrichshafen, Germany, to tune into a seemingly outmoded technology: the radio.

With 198 exhibitors from 38 countries, Ham Radio 2015 was the 40th gathering of the world’s amateur radio operators in this vacation city on Lake Constance. Ham Radio Friedrichshafen is not the biggest amateur radio convention in the world, though: That honor belongs to Dayton, Ohio, whose Hamvention attracts more than 25,000 people annually. (The “ham” is an old jab at amateur radio operators that has stuck around for a century.)

Amateur radio fans (hams in American parlance, or Funker in German) come in many frequencies. The DXers have a passion for making contact around the world and collecting QSL postcards (QSL is telegraphic shorthand for “I have received your transmission”) as records of their achievements. People into QRP (telegraphic shorthand for “reduce power”) try to maximize their transmission distance with the minimum amount of power necessary.

Space is an obsession for some: You can contact the International Space Station or bounce signals off the moon. My knowledge of the amateur radio world comes from my father, a vintage audio collector, which is a whole other thing.

Radio fans were easy to spot in the city: Anybody with an antenna protruding from their backpack or with a shirt emblazoned with a five- or six-character call number was definitely one. (You could get a shirt custom-printed with your radio call number at the convention for just a few euros.) For members of the Deutschen Amateur-Radio Club, “DARC side of the moon” T-shirts also were popular.

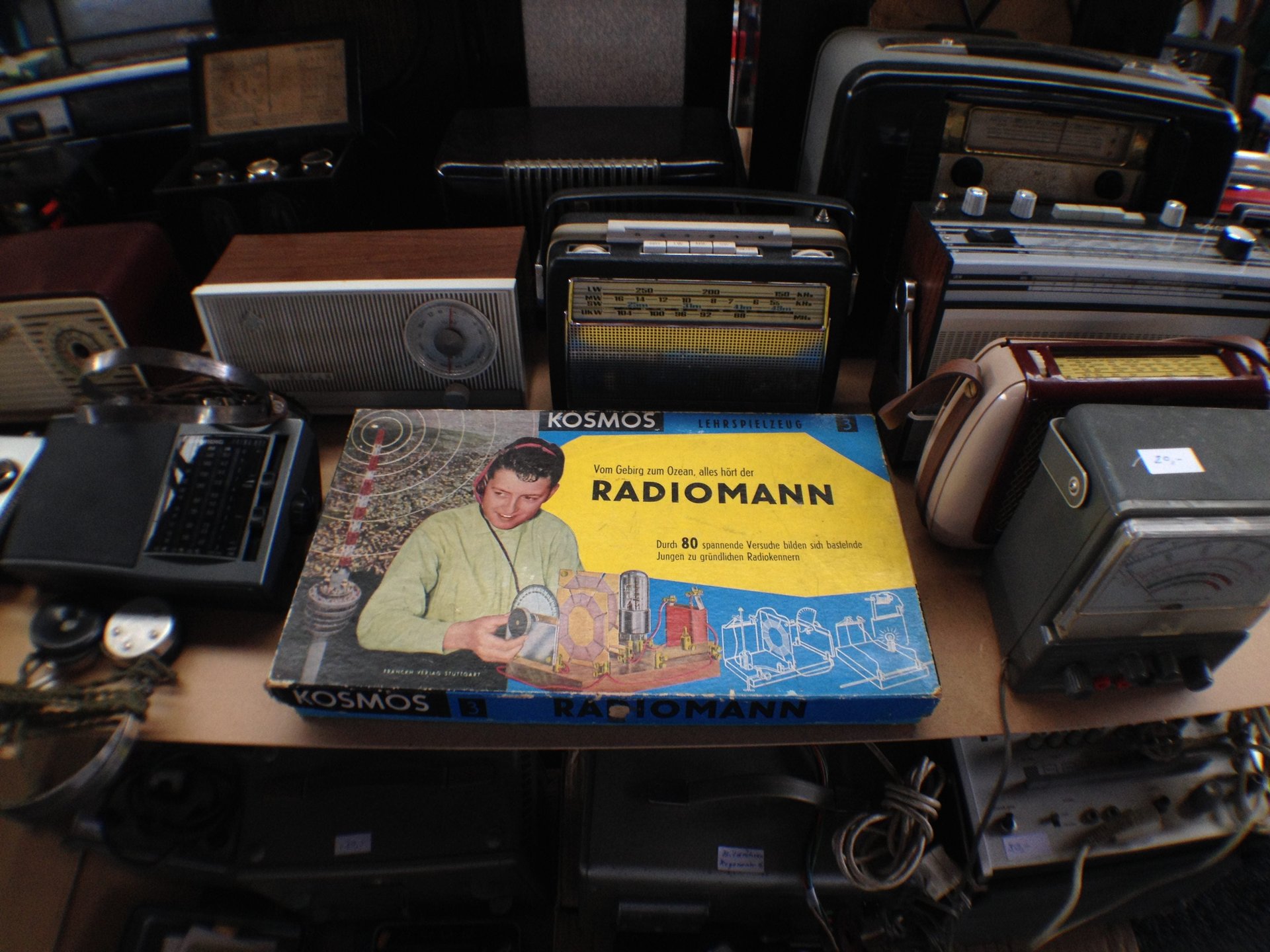

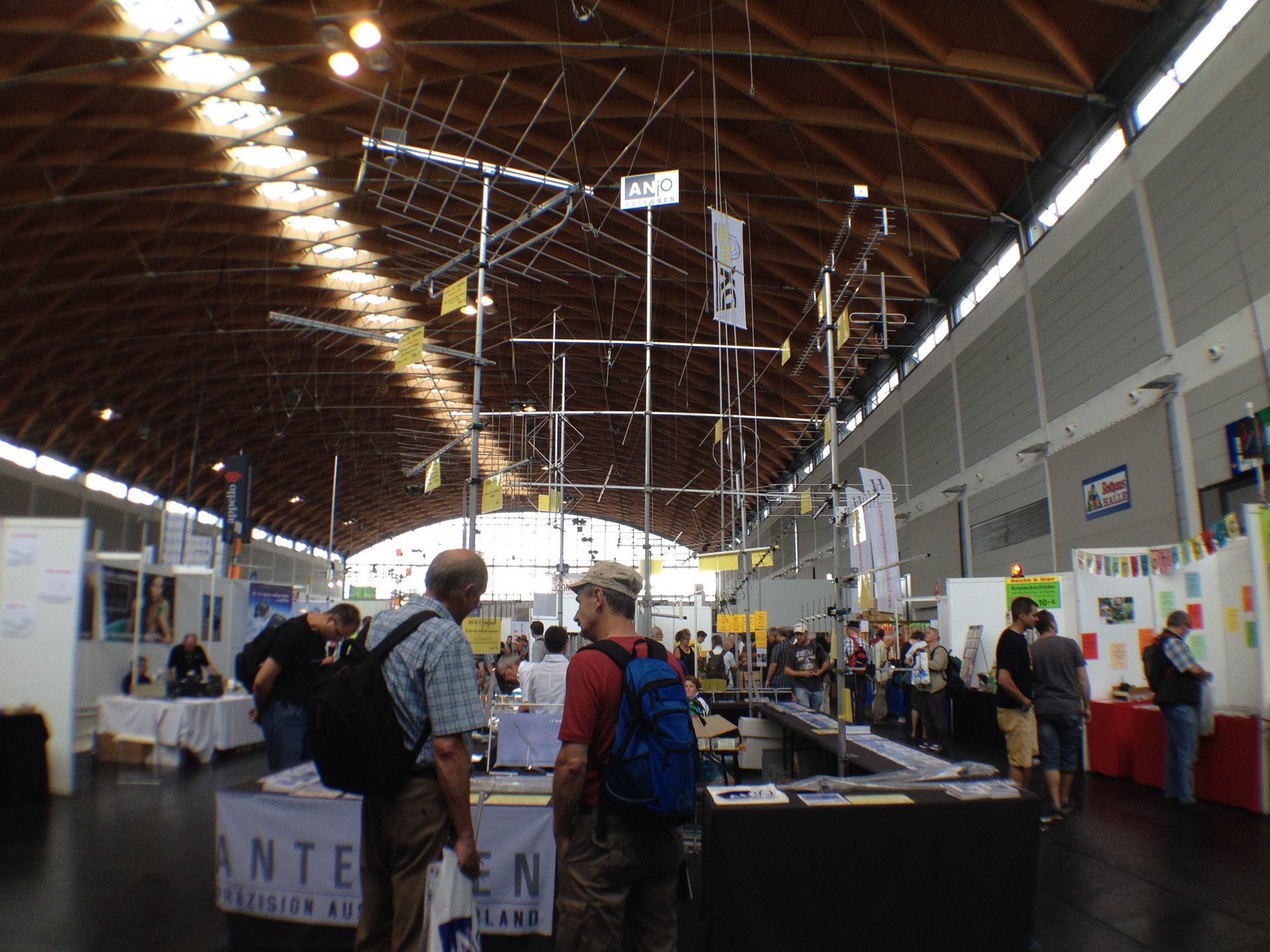

The main Ham Radio convention hall was full of companies selling antennae, receivers and gadgets, as well as booths for national amateur radio groups from Ireland to Israel to Japan. (Salut to the Italian organization, for the free prosecco and parmesan.) A technological flea market filled two more halls, where you could buy vintage receivers and transmitters, examine an original Enigma machine, and dig through boxes of parts, pieces and cables for fixing your own gear.

For the second year at the Friedrichshafen Ham Radio convention, a hall was dedicated to the DIY technology stylings of Maker World, where drones, 3D printers and arduino kits were the name of the game, with an obligatory steampunk booth. At first glance it seemed like modern technology infringing on a group that prefers devices of a certain age, but it was actually a perfect pairing.

Long before Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were building computers in their Silicon Valley garages, radio homebrewers were doing it for themselves in the 1930s and 1940s. A radio fan who found the match fitting told me, “It’s all about experimentation.”

If you follow the history of wireless communication and radio, you’ll see similar arcs with the digital revolution. The advent of transistor radios in the 1950s was like the release of the first iPod in 2001: For the first time, a radio receiver could fit in your pocket—tiny transistors amplified the sound rather than bulky, fragile vacuum tubes. Radios went from expensive living room furniture to ubiquitous accessories.

The hobby has real practical applications even in the digital age: I ended up eating dinner next to a group of Notfunk (emergency radio) volunteers. When disaster strikes and regular communication methods are interrupted, officials can call on members of the International Radio Amateur Union to help.

In the wake of the April 2015 earthquake in Nepal, Technische Hilfswerk, the German federal disaster service, sent a discovery team to determine what help was needed. Notfunk Deutschland volunteers made contact with three Nepalese radio operators and could share up-to-date information with the German federal government, and let the locals know that help was on the way.