It looks like Bank of Japan is boarding the Abenomics train at last

Reuters reports that the Bank of Japan shook hands with prime minister Shinzo Abe’s government on a point of dispute today: inflation targeting.

Reuters reports that the Bank of Japan shook hands with prime minister Shinzo Abe’s government on a point of dispute today: inflation targeting.

Yep—after punting on the issue in their meeting last December, the central bank is backing down and agreed today to a 2% inflation target as a policy goal for monetary loosening, up from the current 1%. The bank will formalize this plan in its two-day meeting next week, which ends Tuesday.

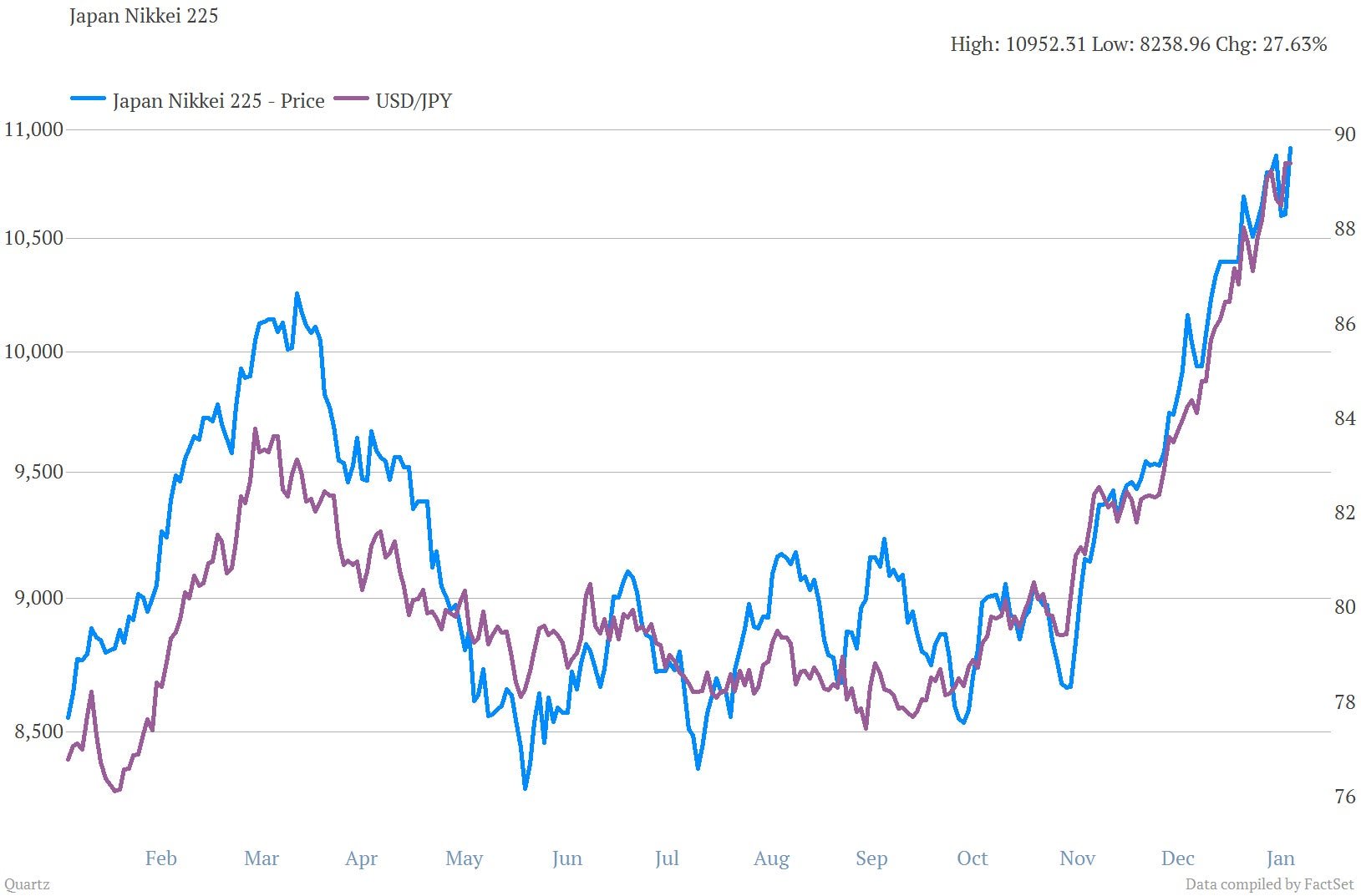

This is a big deal. It’s good for Abe’s push to move the economy into inflationary territory, which is critical to stimulating household and business spending. Plus, the markets love it: Nikkei 225 leapt 2.8% today. Meanwhile, the yen has been hovering around the symbolic 90-to-the-dollar mark, which Abe has been shooting for in his bid to improve the competitiveness of Japanese exports.

But it’s also noteworthy because politicians are one kind of borrower with whom bankers are never supposed to shake hands. This synch-up of the government and the central bank is controversial because, as we touched on recently, central bank independence is a check against profligate government spending made possible by “monetizing government debt.” Lifting this curb could, in theory, allow a government to spend itself into bankruptcy. In this case, Japan issues its own currency and its own debt—and has the third-largest economy in the world—making a solvency crisis, at this point, theoretical.

Theoretical for now. Abe’s scorched-earth approach to both fiscal and monetary stimulus will soon drive Japan’s government gross debt beyond 240% of GDP, by some estimates. At some point, of course, theory has to give way to the reality of having to pay all that back—and at market-set interest rates. And unfortunately for Japan, there are many things that could trigger that.

The bigger deal still, though, will be whether the BoJ announces open-ended purchasing of government and other debt on Tuesday. In its perpetual inflation-phobia, the bank has so far declined to do that—a stance that is thought to have dampened the effectiveness of a monetary policy that has otherwise been wantonly loose, as investors and businesses fear a sudden reversal in policy that could send interest rates up.

Despite the dangers of Abe-BoJ cooperation, Japan desperately needs to escape the deflationary spiral it’s been in for most of the last two decades. BoJ’s move today is a crucial step in making that happen, and a commitment to open-asset purchases will put the money where the BoJ’s 2% target-mouth is.

That means that the upshot of the growing government-BoJ cuddliness is that, increasingly, fiscal prudence and a focus on structural economic reform (e.g. privatization) will fall to Abe alone to prioritize.