How Cuba is using capitalism to save socialism

This is the second in a series of four dispatches this week on the US-Cuba opening. Read the first here.

This is the second in a series of four dispatches this week on the US-Cuba opening. Read the first here.

HAVANA, CUBA—If you are fantasizing about your first trip to Cuba, that fantasy presumably includes cruising down the Malecón, Havana’s seaside promenade, in an open-topped 1957 Chevrolet Bel-Air, with the tropical light playing over the decrepit buildings and the warm sea breeze tickling your scalp. Cigars are probably involved, and rum.

The rum and cigars are produced by state-managed Cuban enterprises. But who is maintaining the classic cars? In many cases, not the Cuban government, but self-employed entrepreneurs.

Allowing limited private enterprise within its socialist economy was how Cuba weathered the collapse of the Soviet Union while still under the US embargo. And now that Cuba-US relations are warming, that nascent private sector is proving a surprisingly fertile common ground for the two governments—albeit for rather different motives.

For Havana, liberalization holds the promise of an economy strong enough to protect the foundation of Cuban socialism—state-run health care, education, and social security programs. In Washington, US policymakers see looser rules around US travel and trade as a way to boost an independent Cuban middle-class isolated by the 50-year embargo.

Selling the Cuban experience

Two of the poster girls of Cuban entrepreneurship are Nidialys Acosta Cabrera and her pristine pink-and-white Bel-Air, Lola.

While there are a lot of old Chevys in Cuba, many are in far less than mint condition—rough paint jobs, doors that won’t close or won’t open, the occasional missing steering wheel replaced with a tightened monkey wrench. With sales of new cars heavily restricted until 2011, Cubans kept the old ones ticking, often replacing the old American engines with new ones purchased in Europe and Asia and jury-rigging whatever else needed to be fixed.

Acosta and her husband, José Alvarez, run a company called Nostalgicar, and as its name suggests, it specializes in the classic cars of Cuba. The couple owns four cars: Lola, José’s baby-blue version named Nadine, and two others that are still being fixed up. But they have restored 18 cars for other owners, who have joined them in an loose coalition to rent the cars to tourists seeking the classic Havana experience. (Cuban regulations require separate approval for individuals to form a cooperative company, and so far Nostalgicar has not been granted it.)

Acosta and Alvarez are part of the private sector that the Cuban government has nurtured since 2011 as it gradually liberalizes its economy. Both were engineers at state-owned enterprises before starting the company, and Acosta says she is grateful to the government for the chance to run a business she’s passionate about.

Some of the challenges Nostalgicar’s founders faced would be familiar to entrepreneurs anywhere. To raise their initial capital, they bought Lola from owners who had left her in their yard for a year, and inherited Nadine from an uncle.

But some were specific to Cuba. For example, commercial advertising is strictly regulated and rare, which is a refreshing experience for a foreign visitor but made it difficult for Nostalgicar to get the word out. The company has to host its website in Canada, in order to reach international tourists. And getting the parts needed to restore the cars is a perennial challenge, thanks to the US embargo. The paint for a 1959 Impala is available in the US, but it’s blocked; other parts are available through middlemen in Miami, but red tape and duties dramatically increase the cost.

The end of the embargo will lower these obstacles. It will also bring a flood of modern cars on to the streets, and more buyers looking to snap up vintage classics. Many would-be tourists fear it will spell the end of the “old Cuba” and the loss of that vintage-car fantasy. But Acosta says all this will ultimately benefit her business.

“Many people in Cuba are looking forward to having new cars. We have had these old cars for many decades, and it is very difficult to fix them and find new parts,” she says. “When the market starts opening up and more new cars start coming, of course we will find fewer [classic] cars in the streets. [But] in my case, my husband, this is a business he loves, and we have in mind to keep buying old cars, but they will be beautiful.”

Capitalism with Cuban characteristics

Fidel Castro opened the economy to private enterprise just a crack after the collapse of the Soviet Union took away Cuba’s economic crutch. The paladares, small private restaurants that dot Cuba and offer better food than most state-run spots, were the most visible result.

But Fidel’s brother Raúl, who took over in 2006, knew more had to be done. Production remained low despite aid from Venezuela, and Cuba’s youth—well-educated by the Cuban system but with few opportunities—were leaving the island in what one American researcher called “alarmingly high proportions.” In an early speech on the economy, Raúl Castro told Cubans that “to have more, we have to begin by producing more, with a sense of rationality and efficiency.”

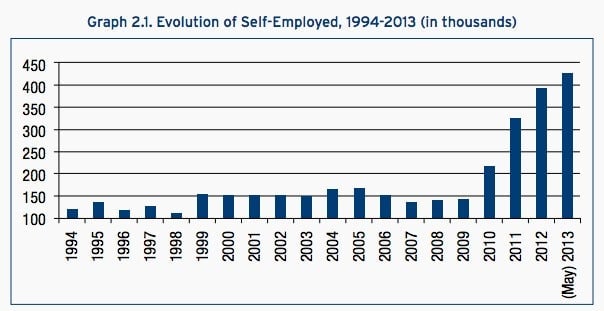

It started simply: Farmers could lease state land, citizens could purchase consumer goods like electrical appliances and mobile phones, street vendors were allowed to sell food, and some state workplace cafeterias were closed. By 2011, when it announced a series of liberalization measures, the government said 500,000 Cubans would lose government salaries in order to fill new small businesses.

These cuentapropistas, or self-employed people, can obtain licenses from a list of jobs, reported to have reached 201 occupations. They include “Buyer and Seller of Records (LPs, 45’s, CDs),” “Disposable Lighter Repair and Refill,” and “Taxi Driver.” But the size of these operations is strictly limited, including by tax rates as high as 50% on profits, and financing can be difficult to obtain.

In 2013, the Brookings Institutions’s Richard Feinberg estimated that there were more than 1 million official cuentapropistas and as many as another million doing it unofficially alongside a government job. By that estimate, as much as 40% of Cuba’s 5 million-person workforce is in the private sector. The Cuban government’s official goal was for 35% of workers to fit in that category by this year.

A push from the US

At a tobacco farm in Pinar del Rio, about two hours outside Havana, Abel Hernández Paez welcomed me into a sweltering barn thick with the smell of drying tobacco; his workers scrambled high in the rafters to adjust poles loaded with leaves. Paez told me that me that before D.17—as Cubans refer to the December, 17 2014 joint announcement of closer US-Cuba ties by Raúl Castro and US president Barack Obama—he might see an American every few months. Now, he sees 20 a week, and has installed a refreshment stand where he can teach visitors about how cigars are made.

That increase is thanks to the Obama administration, which relaxed the travel restrictions to Cuba in January. The goal was, in part, to bolster the growth of Cuba’s private sector, and the middle class it is nurturing, by providing new customers and allowing more investment from the US. Feinberg and others have made this a key justification for ending the embargo: If the Cuban government’s attempt at liberalization isn’t supported with foreign capital, it may falter, as previous attempts have.

Paez’s farm sells 80% of its production at fixed prices to Cuba’s state-owned cigar company, which markets Cohibas and other famous brands abroad, in a partnership with the UK’s Imperial Tobacco. But it can keep the remaining 20%. Working with a different farm that grows the leaves used as the outer wrapper for cigars, as well as with cigar rollers working on their own time, Paez and his workers can produce their own cigars for sale to tourists, supplementing their government salaries.

“Cuban entrepreneurs are very excited about this new policy opening from the US side,” Alana Tummino, who runs the Cuba working group at the Americas Society/Council for the Americas, told Quartz. “There is going to be more space to interact directly with this private sector in Cuba, importing and exporting with them that was not allowed before. But the proof will be in the pudding.”

Though the US and Cuba both favor this opening up of private business, there’s an obvious tension between their longer-term goals. The US hopes its opening will spur democratic reform, while the Cuban government plainly wants to update its economic model while protecting its current political system. As bigger stakes come into play, clashes could occur. But for now, both partners have chosen pragmatism over ideology—or, as Raul Castro put it on D.17, “we must learn the art of coexisting with our differences in a civilized manner.”