Mysteries of the deep-sea: soon to be endangered

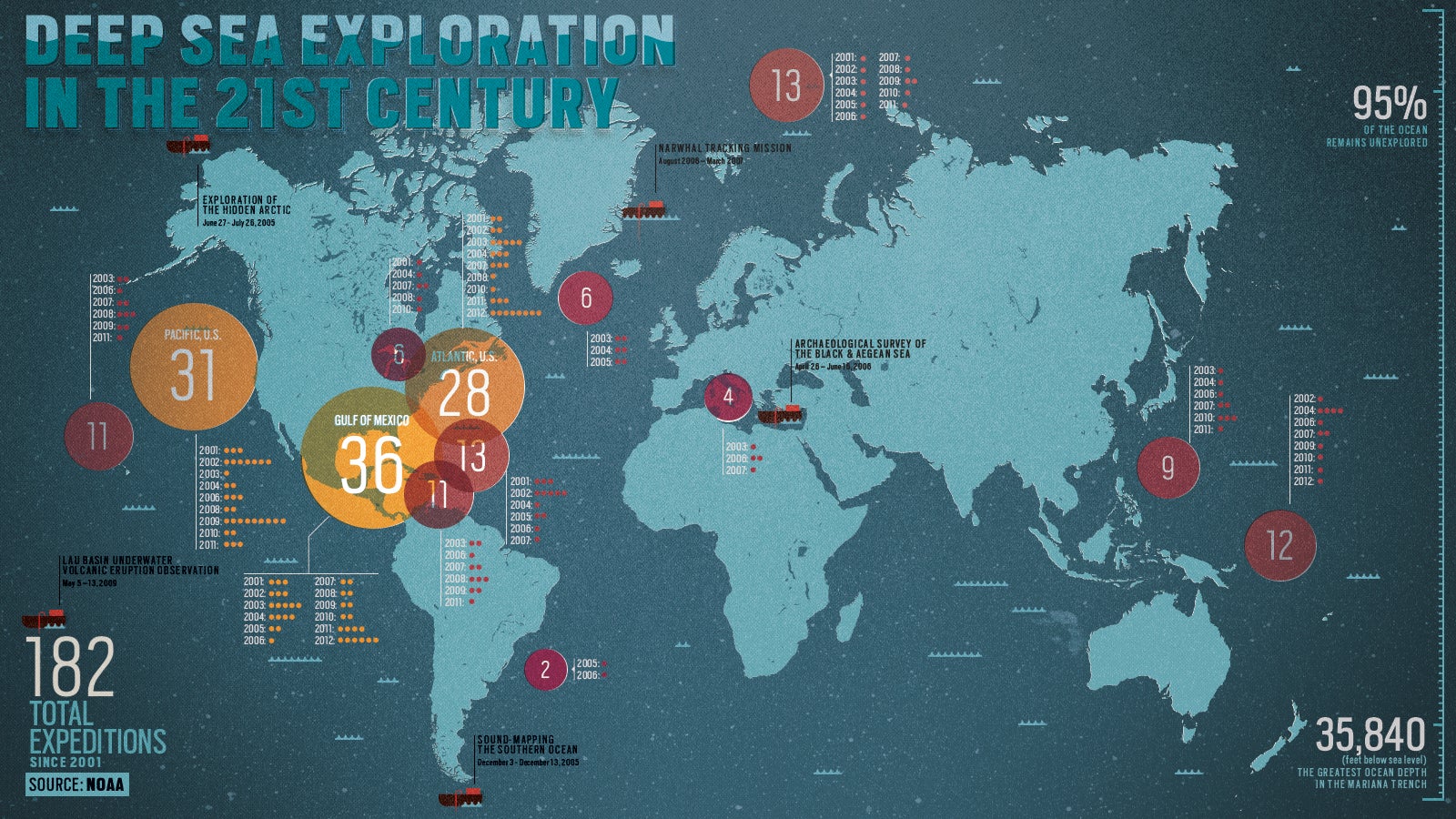

(To see the infographic enlarged, click here)

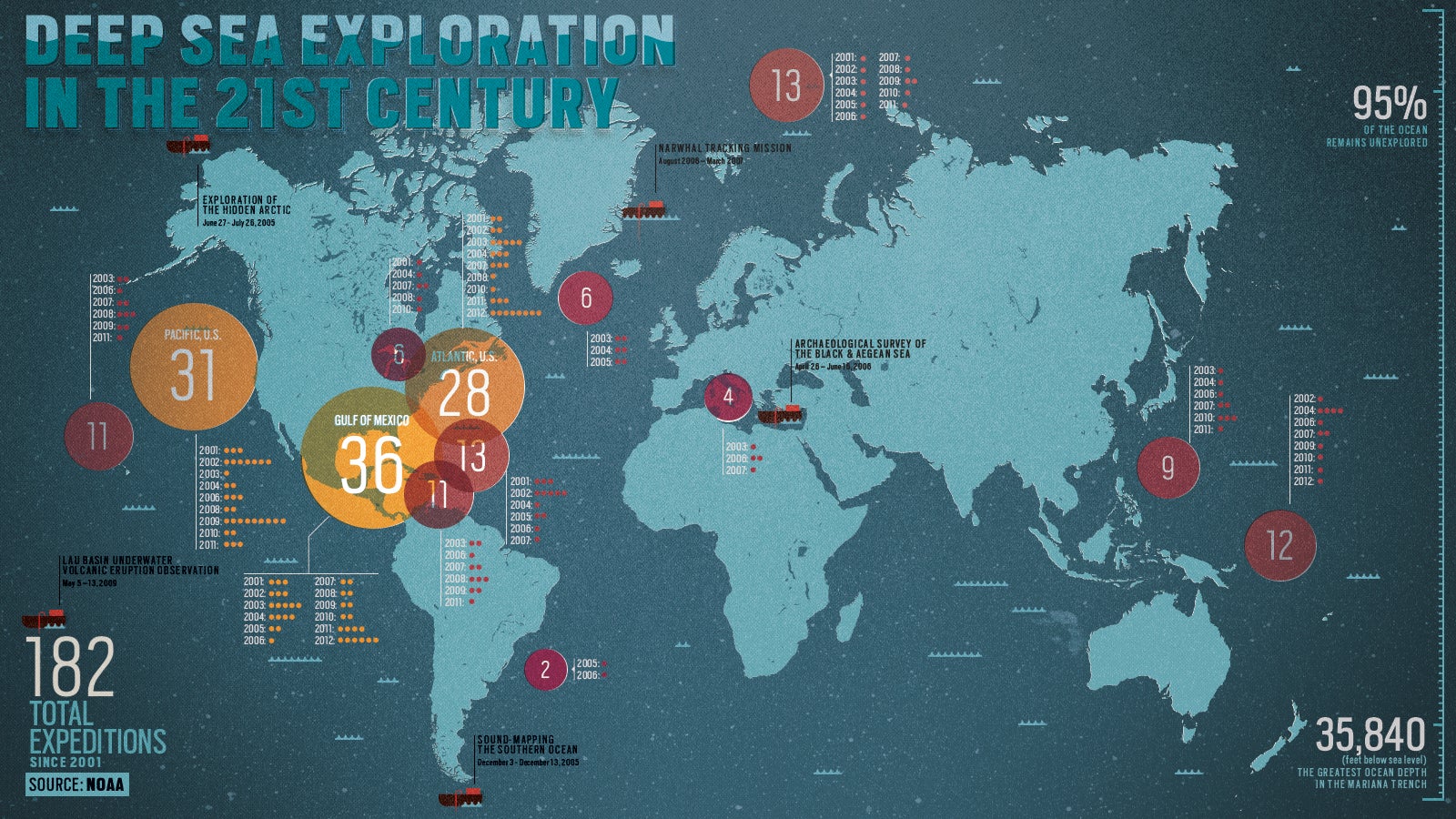

(To see the infographic enlarged, click here)

Over the past year, scientists and researchers have made valuable strides toward corralling deep-water treasures. Innovation and technological advancements have increased the ability to explore foreign, formerly dark parts of the oceans, and appropriately begin to chart those depths.

Last July, patience paid off for a team of scientists. After centuries of stories and physical evidence of its existence (and 10 years of attempted documentation for at least one team member involved), a giant squid was captured on film thousands of feet below the surface in the North Pacific Ocean. The discovery benefitted from two feats of new technology: a small, silent submersible vehicle invisible to squid and a bioluminescent lure. This lure, developed to mimic the bioluminescence of a jellyfish, effectively tricked the elusive predator to get within range of the camera.

Scientists, for the most part, have only been able to study dead specimens of giant squid after they appear floating on the surface or upon shores. The new vessel and lure, however, open up the possibility to study them in situ, which will be particularly valuable in learning about their reproductive cycle and migration path. (Discovery Channel will air footage of the giant squid, possibly the first of the creature in its natural habitat, at the end of January.)

In line with more traditional treasures – those leading to great sums of wealth – deep-sea mining (DSM) is at the center of debate among oceanographers, engineers, and conservationists. As innovations have allowed for DSM to be economically viable enough to extract minerals from hydrothermal vents and other deep-sea depositories, mining companies and countries’ energy arms (like India’s National Institute of Ocean Technology) are racing to lead this discovery. Though deep-sea mining could very well open up a new frontier of energy and minerals in a sustainable way, many scientists are cautious about what DSM could mean to the oceanic ecosystem.

The Papua New Guinean government, in an attempt to lure foreign investors and pump capital into its tiny, stagnant economy, agreed for Nautilus Minerals Inc., a Canadian mining company and the first in the world to explore polymetallic seafloor massive sulphide deposits, to begin mining off its coast in the Bismarck Sea. The mining was met with great resistance from environmentalists and the local fishermen, claiming that the drilling will disrupt the local ecosystem and pose oil-spill threats. This resistance, combined with a turbulent transition in the Papua New Guinean Parliament, has stalled the expedition for now. While the technology to extract valuable minerals – copper in this case – is shovel-ready, there are many legal, environmental, and economic hurdles standing in the way for DSM operations in the South Pacific and beyond.

Whether it be rare sea creatures or evolving deep-sea ecosystems, one researcher is attempting to paint the entire picture. Oceanographer John Delaney is looking to build a mapping system using high-definition cameras and sensors that captures the entire ocean and all of its activity and movement (VIDEO: Full TED Talk Presentation). With the growing trend that big data can explain, and help predict, natural events, Delaney’s cabled network will capture interactive processes to better elucidate treasures like giant squid and minerals, as well as most treasured of them all: the unknown.

This article is written on behalf of Cadillac and not by the Quartz editorial staff.