The father of the American shopping mall hated what he created

The shopping mall is dead. The shopping mall is alive. The shopping mall is reborn.

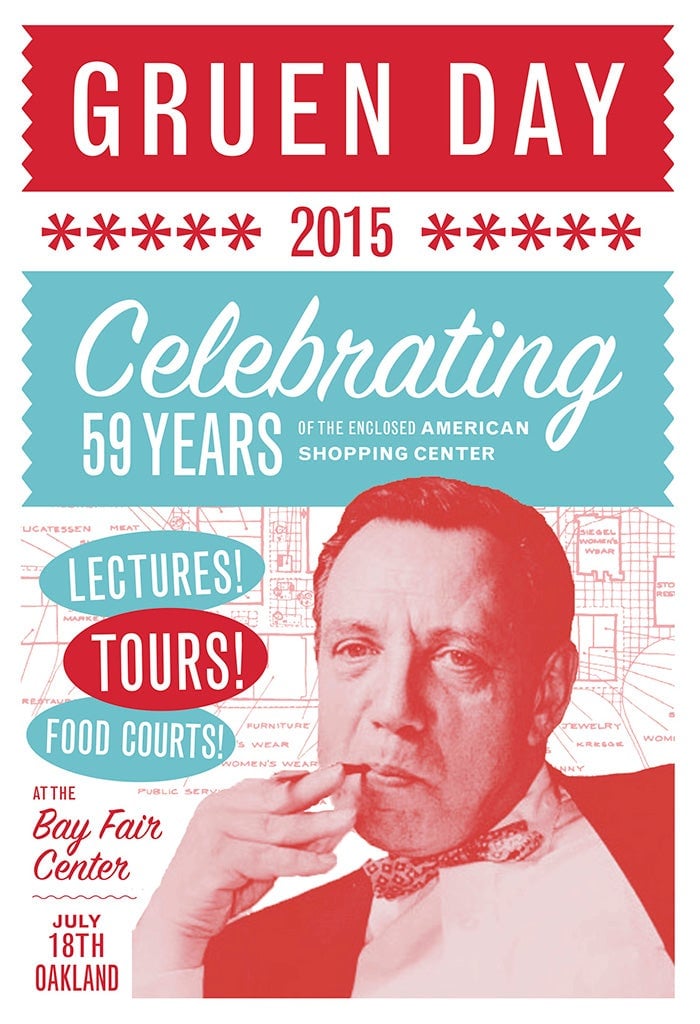

As sociologists and urban planners debate the relevance of these classic American brick-and-mortar shopping spaces in the era of e-commerce and Amazon Prime Day, a group of architecture enthusiasts will gather this weekend to celebrate the birthday of Victor Gruen, the man known as ”father of the modern shopping mall,” and the first annual Gruen Day.

In the invitation to the event, on July 18 at the Bay Area Fair Center mall in a suburb of San Francisco, California, organizers Tim Hwang and Avery Trufelman of the Bay Area Infrastructure Observatory challenged the notion that malls were a bad idea from the beginning. “While it’s easy nowadays to dismiss enclosed shopping centers as boring eyesores, Gruen Day celebrates the important role they were originally intended to play in civic life,” they explain.

Gruen’s original vision

Hwang and Trufelman point to Gruen’s role in creating what sociologists call a”third place”—safe, neutral public spaces outside of one’s home or work that, in Gruen’s words, “provide the needed place and opportunity for participation in modern community life that the ancient Greek Agora, the Medieval Market Place and our own Town Squares provided in the past.”

While online shopping has usurped the primacy of the suburban shopping center as the venue for commerce in the US, in Asia and many pockets around the globe, these climate-controlled mega structures still remain thriving hubs for commercial and cultural activities.

An idea backfires

Today shopping malls are seen as culprits in the rise of American car culture and the decline of walkable downtowns. But the inspiration for the shopping mall is in fact the town center of Vienna. Gruen, an Austrian Jewish architect born Viktor David Grünbaum, immigrated to New York with $8 in his pocket, and when he designed the first enclosed shopping centers in the mid-1950s, he envisioned a communal gathering like the one he knew back home, with a lively mix of commerce, art and entertainment.

Gruen’s first grand shopping complex, the 800,000-square-foot (74,000-square-meter) Southdale Center in Edina, Minnesota, had fountains, an aviary, and even a large art installation by the prominent mid-century artist Harry Bertoia. A socialist who hated cars (“Their threat to human life and health is just as great as the exposed sewer,” he once said), Gruen designed the development with long promenades and parking lots purposely built far away to encourage walking. In drawing Southdale’s original plan, Gruen imagined a medical center, schools and residences, not just a parade of glitzy stores.

When it opened in 1956, Southdale was seen as the most exciting idea in urban development.

Since then over 1,200 shopping centers have sprouted up across the US. But Gruen never imagined that these mega-structures he had envisioned as town plazas would contribute to the suburban sprawl that he despised, and to the demise of the urban high street.

“I am often called the father of the shopping mall,” he once said, reflecting on his career two years before his death in 1978. “I would like to take this opportunity to disclaim paternity once and for all. I refuse to pay alimony to those bastard developments. They destroyed our cities.”

Dead malls, reincarnated

But almost 60 years since his Southdale opened, Gruen’s vision for America might actually become a reality. In a movement that begun in 2000, hundreds of “dead malls” or “greyfield shopping centers” (pdf) across the US have been transformed into mixed-use neighborhood spaces, much as Gruen had hoped.

In Hickory Hollow Mall in Nashville, Tennessee, the former site of a JC Penney is now a library and the Dillard’s department store is now a satellite campus for Nashville State Community College. Nearby, the Vanderbilt University Medical Center took over the entire second level of the 100 Oaks Mall. The city hall in Voorhees, New Jersey relocated to the sleepy Echelon Mall and in Arizona, a once vacant Fiesta Mall Macy’s, is being converted to office spaces.

Gruen’s vision is perhaps embodied most completely in the skeleton of the City Center Mall in Columbus, Ohio. As the Atlantic reports, the space that closed down in 2009 has been converted into the Columbus Commons, a seven-acre park in the heart of downtown with a performance space, cafes, bocce courts, lush gardens, a life-size chess set and new residential buildings and retail shops.

For more on Gruen’s legacy, check out this illuminating podcast, produced by Trufelman.