From potato farming to a $23 billion Chinese takeover target: Micron Technology and the history of tech in America

Tsinghua Unigroup’s planned $23 billion bid to purchase Micron Technology, made public last week, hasn’t been confirmed by either party. But the idea of Micron being taken over by a Chinese company has already raised so much concern on Capitol Hill, including from John McCain, that Micron executives are privately warning off their potential suitor.

Tsinghua Unigroup’s planned $23 billion bid to purchase Micron Technology, made public last week, hasn’t been confirmed by either party. But the idea of Micron being taken over by a Chinese company has already raised so much concern on Capitol Hill, including from John McCain, that Micron executives are privately warning off their potential suitor.

What is this little-celebrated national asset?

While Micron may not be a well-recognized name in an industry now dominated by Apple, Asian manufacturers, and app-based newbies like Uber, the Boise, Idaho company is one of America’s first, most successful tech startups. It is also one of the US’s last major manufacturers of dynamic random access memory chips, known as DRAM, after clinging to domestic chip-making as rivals folded and got bought out.

In many ways, the homegrown giant’s history mirrors the rise and fall in tech manufacturing in the United States. Micron’s modest origins and low-profile belie its global influence, and now even with a Tsinghau deal unlikely, Micron’s future looks uncertain.

To be fair, though, that’s just as true now of the company as it was when the firm began.

Micron’s potato-farming roots

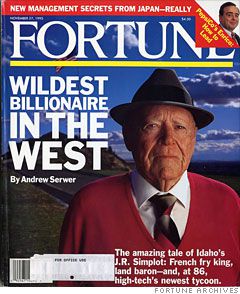

One Micron’s earliest financiers was J.R. Simplot, an Idaho potato farmer who earned his first riches by engineering a more cost-efficient hog-slop. Simplot later devised other ways to turn potatoes into cash—he was the first to dehydrate them, which got him a deal with the US military, and the first to freeze them, which got him a billion-dollar deal with Ray Kroc, founder of McDonalds.

But Simplot’s most important endeavor arguably came along when he met Joe and Ward Parkinson, twin brothers from southeast Idaho. The two were looking for someone to finance production for a 64K DRAM chip—a versatile chip that functions as the short-term memory for many electronics. Micron wasn’t the first company to make 64K DRAM chips, but they wanted to make a version that was the smallest on the market.

In 1980, Simplot gave them $1 million for a 40% stake in the company. Just 15 years later, it would be worth $4 billion, earning him the title “The wildest billionaire in the West.”

In its early days, Micron sold its 64K DRAM chips to some of the first companies to make and sell personal computer for masses, including the Commodore 64 home computer. Sales were strong enough to take the company public in June 1984.

But the semiconductor industry is notoriously cutthroat, and Micron’s memory chips quickly became a commodity component that was highly subject to price wars. Setting up a facility for producing DRAM is expensive—it costs cost $3 billion nowadays—with cyclical upgrades every 18 months costing anywhere from $100 million to $3 million.

Since DRAM powers nearly every PC and lots of other electronic devices, enterprising businessmen—or rather, technocrats—have viewed it as a potential goldmine. Their success, though, is closely tied to device sales. If they don’t meet expectations, chip makers suffer oversupply and further price drops.

“DRAM will never die because every electronic device needs DRAM,” says Avril Wu, Assistant Vice President of DRAMeXchange, a division of Trendforce, which researches the semiconductor industry. ”It requires a big investment, but you can make big money if you play the right moves.”

Micron executives were not immediately available for an interview for this article.

Battling Japan, then Korea

Right around the time of Micron’s 1984 IPO, Japanese rivals crippled the US electronics and manufacturing industry by offering cheaper versions of products once Made-in-America. Automobile makers, TV set vendors, and other sectors faced stiff competition from conglomerates from the East. During the the eighties, 11 of the US-based DRAM makers ceased producing DRAM domestically, including Intel, which was the first firm to bring DRAM chips to market.

But Micron held out. In 1985, it became the first company to file a complaint with the International Trade Commission accusing Toshiba, Fujitsu, Hitachi, and three other firms of dumping—the practice of pricing goods deliberately below cost in order to bankrupt competitors. Four years later, with a little help from the government, Micron was alive and well, with 900 employees. “For this little Podunk company to go toe to toe with the Japanese in an area that the Japanese dominate is a pretty remarkable story,” one analyst told the New York Times in 1989.

Japan’s fast rise quickly stagnated, as chip exports led to a trade surplus that bloated the value of the yen. In their place came the Korean conglomerates, who largely did to Japan’s chipmakers what Japan did to the US—use government subsidies and cash from other parts of the company to flood the chip market and drive prices down. Ironically, Micron was partially responsible for the rise of market leader —it was one of the first chip makers to license its patents to Korean giant Samsung. A few years later, Micron accused Samsung of price-dumping.

Surviving boom and bust

Boom and bust cycles in the DRAM industry continued throughout the nineties. Korean firms consolidated, and Japanese players dropped out. The Taiwanese made a brief appearance.

Micron became the club of last-men-standing, buying up firms that couldn’t survive during the down periods.. It purchased the DRAM division of Texas Instruments for $800 million in 1998, and later bought Japan’s Elpida in 2012 for $2 billion, rescuing it from bankruptcy. The latter acquisition was particularly well-timed—Elpida was a supplier to Apple, a stable electronics vendor if there ever was one. Around the time of the purchase, Micron received a $250 million payment from an unnamed entity, rumored to be the Cupertino-based hardware firm.

Micron’s longevity can be partially attributed to savvy acquisitions like these. It purchased nine companies between 1998 and 2013.

“Micron was a very different company. Usually when companies are optimistic, they spend a lot of money to invest in capacity expansion,” says Avril Wu. “But Micron never really did that. If they ever increased capacity, it was because they took the opportunity to buy other companies, rather than spending a lot of money to build a new [production facility].”

Throughout its 37-year history, Micron quietly evolved into a global juggernaut.

Though not as well known as Qualcomm or Intel, the company has offices in 13 countries and employs over 30,000 people, 5,000 of which remain in Idaho. In addition to Boise, the company has manufacturing operations in Utah, Virginia, and abroad. The company is easily the largest in the state, with a current market cap at $22 billion—electricity company Idacorp is at about $2 billion. It’s single-handedly representing the United States in an industry now dominated by Korea, after years of fragmentation across East Asia.

Even today, Micron’s financial and stock performance remain heavily tied to demand for DRAM, and particularly PC sales.

In October 2011, the company was trading below $5 a share, but thanks to smartphone sales and the Elpida deal, it hit a ten-year high of $35.95 in November 2014. Nine months later, Micron’s stock has fallen by 49%, after revenue and earnings disappointed. Even if the Tsinghua deal goes nowhere, Micron, the perennial acquisition hunter, is now seen as an acquisition target itself.

China’s tech ambitions

Tsinghua Unigroup’s bid for Micron, should it materialize, would undoubtedly face scrutiny from US regulators. Many analysts believe it is unlikely to be approved.

But the very discussion of a deal signals a new geopolitical era for US technology firms. The eighties and nineties saw Asian conglomerates squeeze out American manufacturers with lower-priced commodity goods, putting blue and white collar employees out of work.

Now, America’s remaining tech firms are wrestling with a new problem—how to access the massive Chinese market without losing control of their own intellectual property. China consumed about 20% of the world’s total DRAM output in 2014, and is expected to consume about 40% by the end of 2015. Companies like Micron can’t afford to be shut out of the market.

But the Chinese government is eager to boost its own domestic tech sector, and its strategy for doing so appears to be coercing foreign companies to share their intellectual property, or taking over. Companies like Intel and Qualcomm have formed investment deals with government backed entities, which serve no strategic advantage other than appeasing authorities. It’s not clear if these deals will ensure continued access to the market, or are the beginning of a gradual neutering.

Judging by recent comments from CEO Mark Durcan, Micron remains committed to its home state.

“This company will be headquartered in Boise for a long, long time,” Adams told the Idaho Chamber of Commerce last December. “Eighty percent of our research and development is here in Boise. Our employee base over the last few years has grown by over 20 percent. We will continue to invest, and we have to invest in new things beyond just what we are known for.”

If, against the odds, a takeover by Tsinghau does actually happen, the two firms would have at least one thing in common—farming roots. Tsinghua Unigroup chairman Zhao Weiguo was once a sheepherder.