Airbnb compared itself to Ellis Island, obviously really needs a history lesson

Lately Airbnb can’t seem to keep its foot out of its mouth. Right after releasing a much-derided, creepy ad that suggested the service helps you understand whether humankind is good by allowing you to sleep in people’s beds (that generated this fun spoof) the home-rental company has a new campaign comparing its homestay service for travelers to the treatment that immigrants endured coming to America via the iconic and notorious processing center at Ellis Island, in New York.

Lately Airbnb can’t seem to keep its foot out of its mouth. Right after releasing a much-derided, creepy ad that suggested the service helps you understand whether humankind is good by allowing you to sleep in people’s beds (that generated this fun spoof) the home-rental company has a new campaign comparing its homestay service for travelers to the treatment that immigrants endured coming to America via the iconic and notorious processing center at Ellis Island, in New York.

A piece of interactive advertising featured in the New York Times presents the history of Ellis Island—the entry point for 12 million immigrants who came to the United States between 1892 and 1931—through pictures, data and interviews with descendants of the migrants who passed through.

The ad—a rather long and inconsistent scroll-down feature—presents Ellis Island in glowing terms: “Over a span of roughly 70 years, Ellis Island grew from an anonymous outcropping in New York Bay to an iconic symbol of American multiculturalism. Equally important to its legacy is the culture of hospitality beyond its shores.”

But as The Observer first pointed out, the picture Airbnb paints of the reception immigrants passing through Ellis Island received may be a touch too rosy. A 1903 archival document from the facility describes the treatment of immigrants as less than hospitable. They were inspected and “aliens who do not appear normal are turned aside, with those who are palpably defective, and more thoroughly examined later.” They were then grouped and interrogated, then either deported, quarantined, or sent off to trains or relatives, with precautions taken to protect them from “the boarding house runners’ and other con men who lie in wait for them at the Battery.”

Those boarding houses, again, sound much more pleasant in Airbnb’s telling: “Coming through Ellis Island was not always easy,” the ad acknowledges. “Some newcomers were sent home, others spent months in quarantine.” But for those allowed to stay, the ad explains, “Private residences, both middle and lower class, offered immigrants simple shelter and sustenance for a reasonable price.” At these boarding houses, immigrants found “valuable support networks” and “a sense of community,” and benefited from America’s “emerging culture of hospitality.”

Community may well have formed, but it’s also true that many of those 19th-century immigrants would end up in squalid tenements in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, often without indoor plumbing or running water, and with rats spreading disease. Children were particularly susceptible to the epidemics of typhoid, cholera, tuberculosis, and pneumonia that swept the overcrowded apartment complexes.

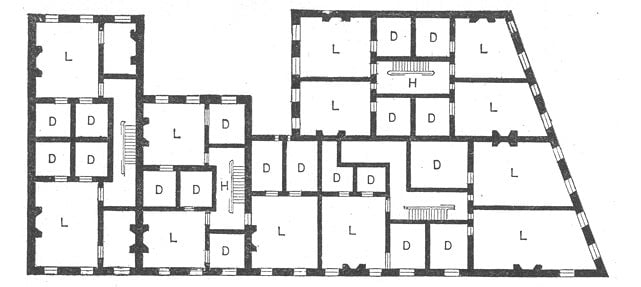

The social reformer, writer, and photographer Jacob A. Riis showed all this in brutal detail in his 1890 book, How The Other Half Lives. Riis described conditions that even the most hardy Airbnb customer would balk at: apartments divided up to house 12 families, with unventilated bedrooms just a few feet square.

Airbnb describes these close quarters as a bonding experience. “It was not uncommon for a sense of family to develop,” the ad asserts, quoting Megan Smolenyak, a genealogist: “’If you look at old census records you’ll see lots of immigrant families living together,’ Smolenyak says. ‘The whole family, plus anywhere from one to 10 other people, all crammed in the same house.'” (Quartz has emailed Airbnb for a comment, and will update this post with any response.)

Sure, Airbnb can sometimes be a little unpleasant. But it seems a bit unfair to compare it to what immigrants struggling ashore a century ago faced.