Why the great robot panic makes no sense

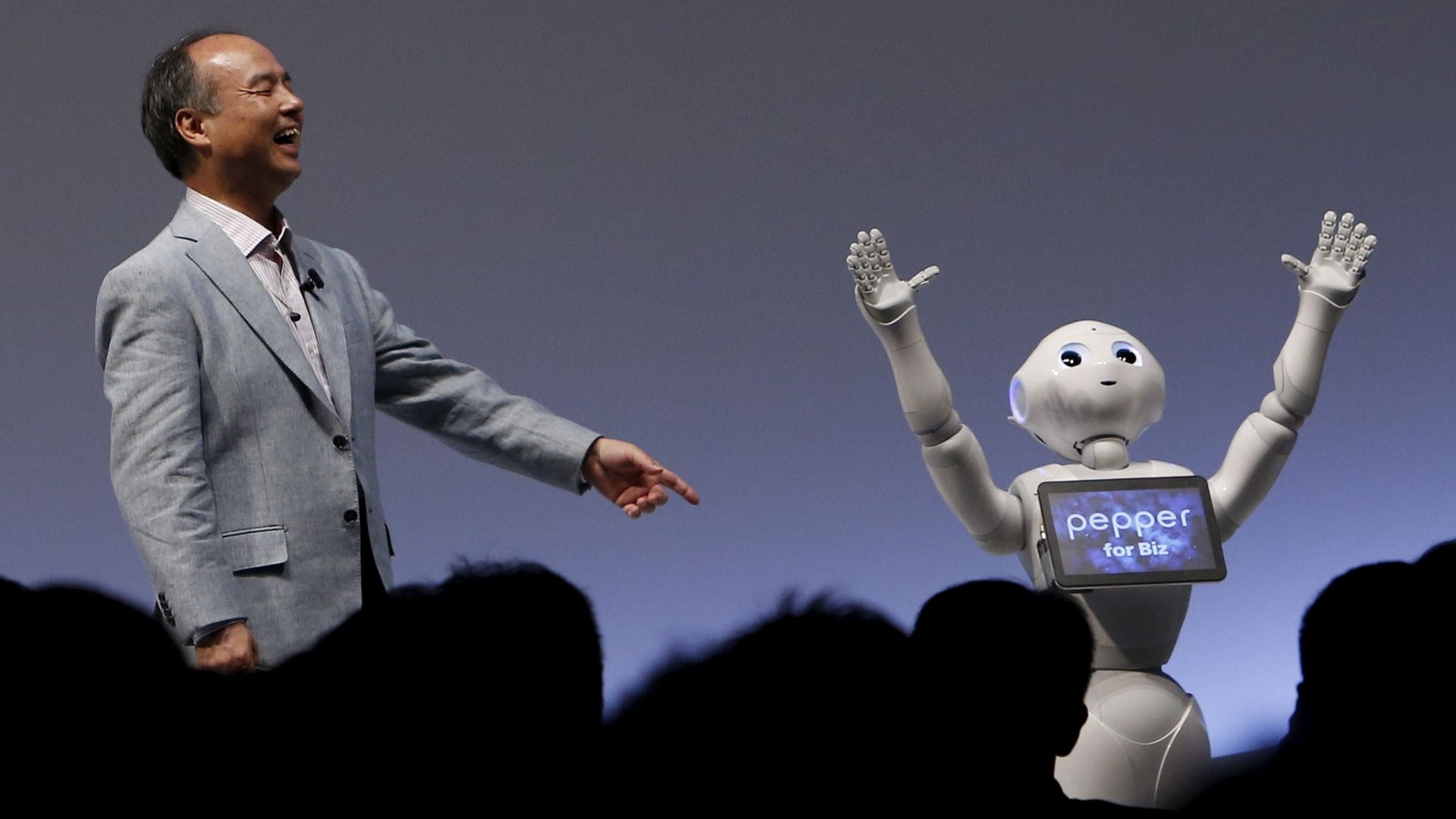

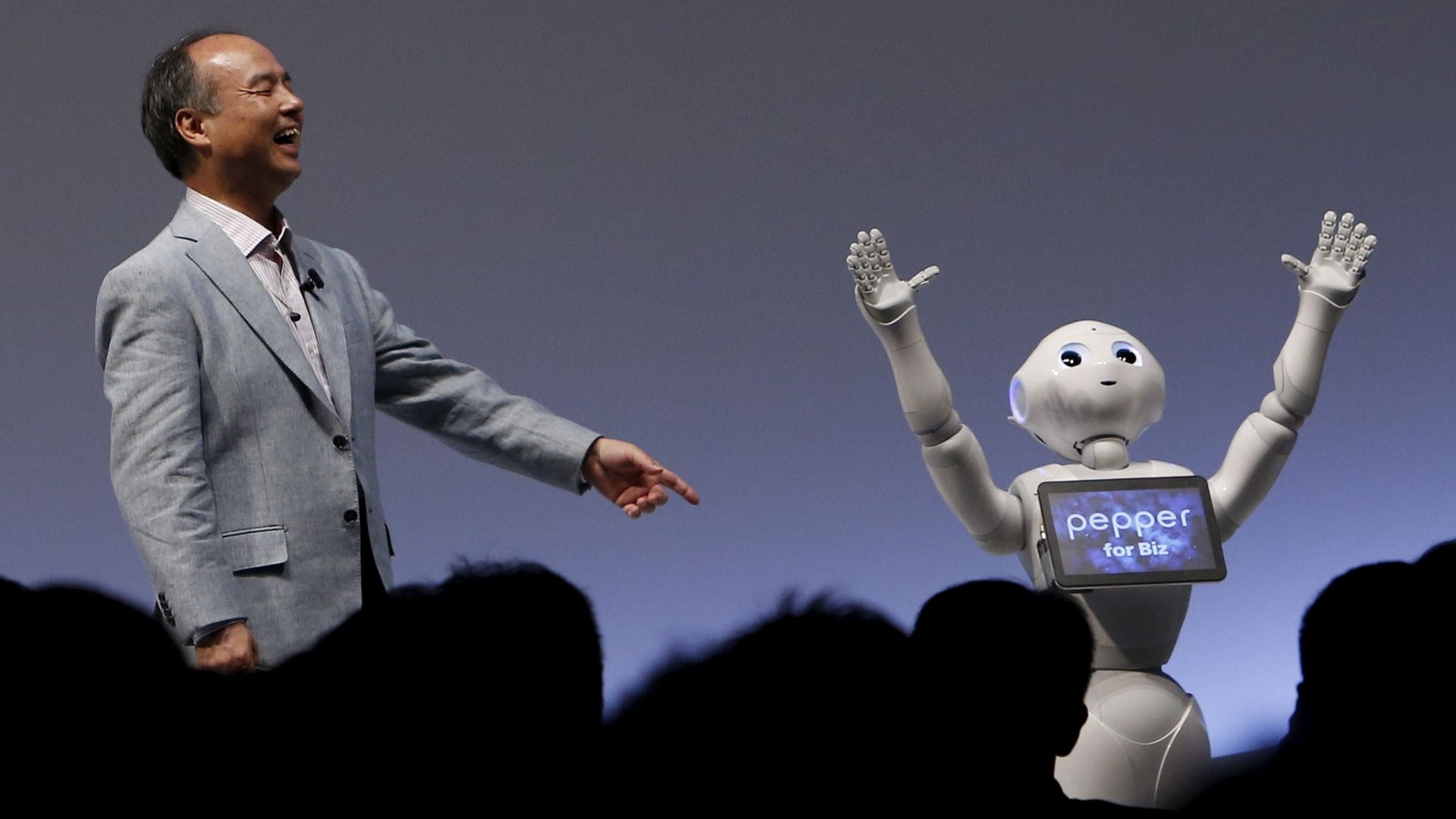

Robots are having a moment.

Robots are having a moment.

If we can, let’s lump together a few robotic things: Elon Musk, Bill Gates, and a bunch of other technology figures urged governments to keep scary artificial intelligence away from guns; Uber has been criticized in advance for potentially replacing drivers with robotic cars that have yet to be developed or manufactured; opponents of the US push for a $15 minimum hourly wage have stoked fears of automated kiosks taking McDonalds jobs.

Robots! They freak people out. And they really shouldn’t, because if anything, we need many more of them. This chart shows why:

It measures something economists call “total factor productivity.” TFP isn’t productivity in terms of “output per hour” but rather an economic measure of everything that goes into making something besides capital and human labor: technology, business processes and methods—basically, the force multiplier that makes the first two inputs produce more value together.

As you can see, during the post-World-War-II golden age of the US economy, TFP soared. Refrigeration, transistors, jet aircraft, plastics, the interstate highway system, more college-educated workers thanks to the GI bill; all of it made investment and work more productive. Americans worked less and earned more, and economic inequality was reduced.

But somewhere around 1974, TFP stopped growing at that wicked pace, and despite a 1990s boost attributed to internet and mobile communications, we’re still stagnant. Greatly stagnant, in some views. And ironically, we’re most afraid of robots when we most need them—and perhaps the 1960s science-fiction obsession with friendly robots now makes more sense.

As Matt Yglesias argues in his robopologia this week, automation is one of the few obvious ways out of this productivity trap. Most of the really advanced technology being built right now outside of that arena does have real benefits for people, but doesn’t solve the problem of generating more prosperity.

While people fear that robots will take their specific jobs—the Luddite argument—the reality is, we haven’t seen that happen recently. The big hit on US wages in recent years hasn’t been automation but instead cheap labor from China—and a lack of productivity enhancement that would make US workers productive enough to outwork their cheaper foreign counterparts.

But what happens when, say, automated cars put drivers out of business or kiosks mean less employment at McDonalds? There will have to be a major social transformation of some kind, where people in general work less and other kinds of services are valued more. It won’t be easy! But it could be fun: A world where human flourishing is increasingly separate from menial labor.

That change will probably be easier than the other option: If TFP growth keeps lagging, it will become increasingly difficult to generate the economic output to support things like the US welfare state. Just look at this chart from the White House budget office, which shows what the deficit will look like in the future if productivity increases by 0.25 percentage points more than the forecast, or 0.25 percentage points less:

That kind of fiscal pressure on the government will be just one symptom of our sad, robotless future.