Black lives matter, lion lives matter, and they’re both in jeopardy for the same brutal reason

Whose lives matter?

Whose lives matter?

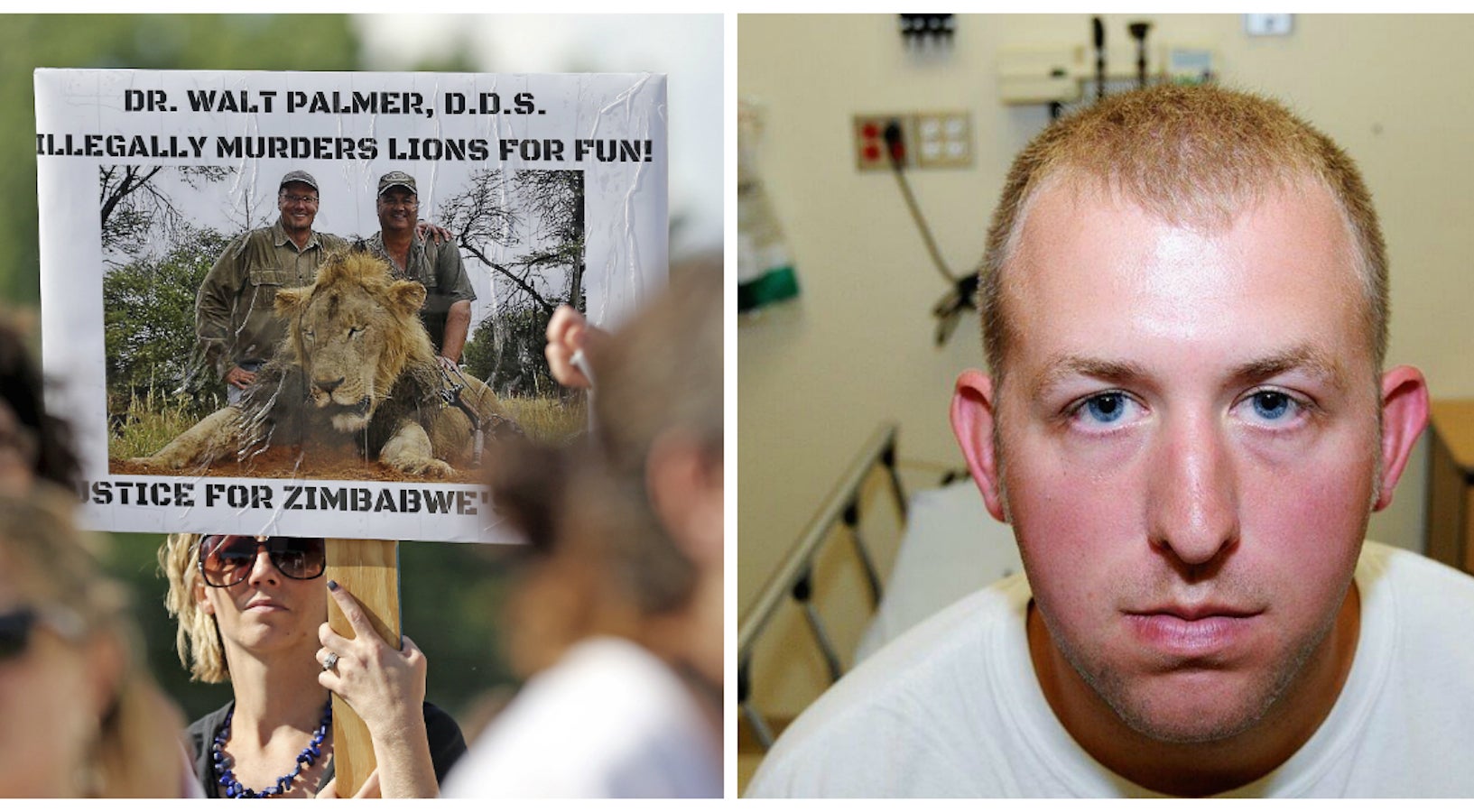

Over the last couple days, the answer to that has been unambiguous. Lion lives matter—and in particular, the life of Cecil the Lion. Cecil, a gentle, friendly (and ecologically threatened) creature, lived in Zimbabwe’s Hwange Natural Park, where he was a favorite with locals and tourists. On July 1, Cecil was killed by Walter James Palmer, a Minnesota dentist with a penchant for big game hunting. Palmer’s guides lured the lion out of the park, where hunting is illegal, so that Palmer could shoot Cecil with a crossbow. He then tracked the wounded lion for 40 hours before killing him with a rifle.

The striking brutality and callousness of the hunt has spurred a massive outpouring of grief and anger, from Jane Goodall to Minnesota children. Petitions demanding justice for Cecil has garnered hundreds of thousands of signatures. Jimmy Kimmel broke down in tears on his show. Palmer has been widely vilified (and doxxed) on social media.

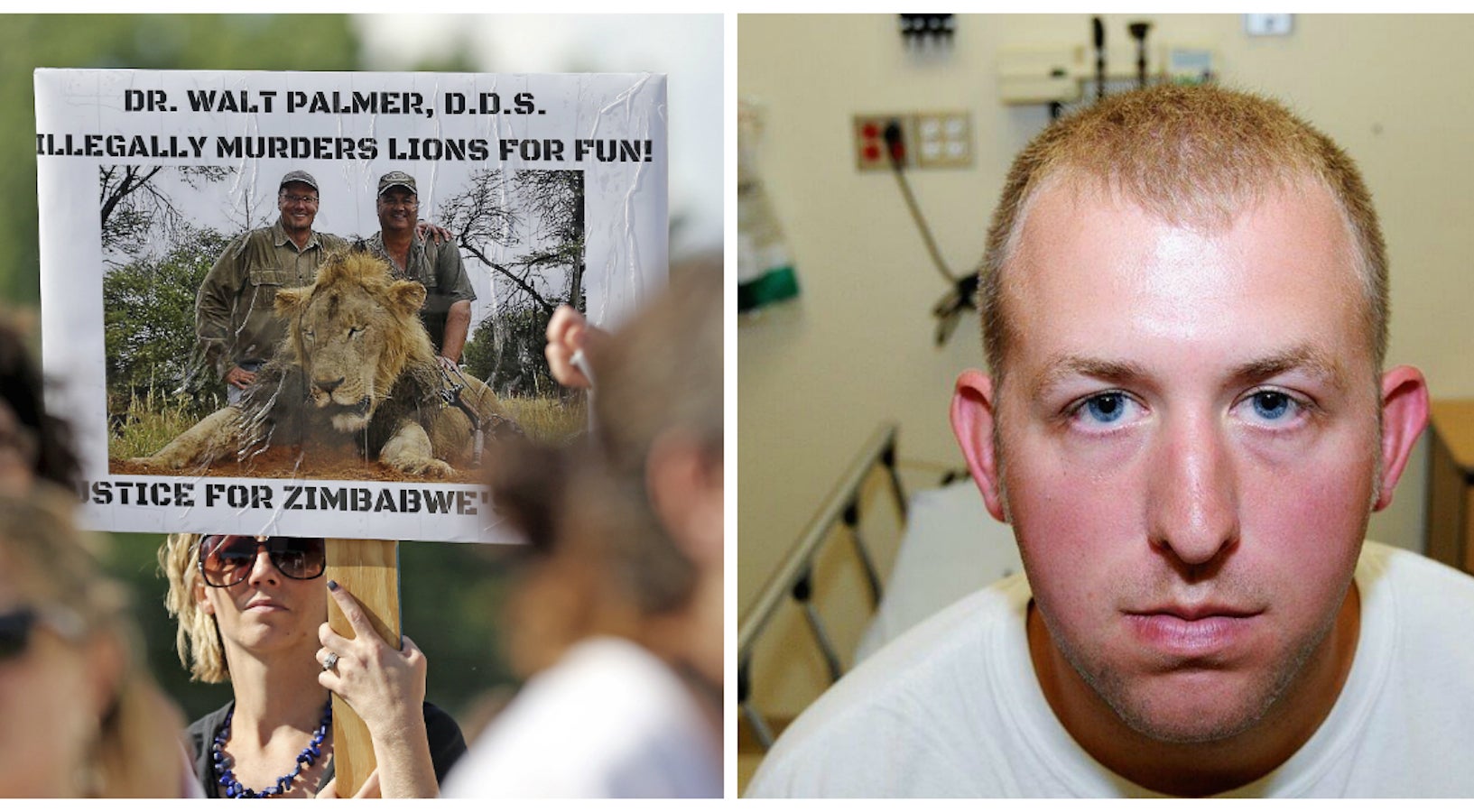

But even as the world mourns the death of a charismatic feline, many black Americans have expressed frustration. The US, they’ve pointed out, seems to care more about a lion being killed thousands of miles away than it does about men and women of color dying much closer to home.

“Staggering racial inequalities in cities + accompanying disparities; centuries of racism + decades of segregation; POC dying in custody, racialized police bruality … But Americans participating in big game hunting is what we single out as a national embarrassment,” Zoé Samudzi, a researcher, activist and project assistant at the University of California at San Francisco wrote with bitter eloquence on Twitter. “Supporting black folks is a less popular cause than those innocent vulnerable animals, we fucking get it.”

Samudzi and her fellow activists’ anger is understandable; Jimmy Kimmell didn’t weep for Sandra Bland. At the same time, though, it’s worth pointing out that the cultural and socio-economic circumstances which allow for the killing of black people in the United States are linked in many ways to those which allow for the killing of lions in Zimbabwe.

Palmer reportedly paid upwards of $50,000 for his lion-killing package. That’s just about the median household income in the USA.

Palmer is rich by comparison to his average fellow Americans—and even richer by Zimbabwean standards, where GDP per capita is less than $1,000. Cecil’s death was therefore enabled by a massive concentration of wealth. Income inequality has been increasing in the US for decades; in 2013 it was higher than it had been since 1928.

Currently, the top 1% of Americans earn about 25% of income in the United States; the bottom 90% share just less than 50%. Similarly, the top 1% globally hold almost half the wealth in the world, while the bottom 50% have less than 1%.

African nations aren’t going to turn down money from wealthy tourists like Palmer, because, effectively, wealthy people like Palmer are the ones who have money.

The growth in income inequality, locally and globally, is closely linked to the African-American experience with the police state as well. Prison rates in the US—especially among black men—have skyrocketed since the ’80s, in line with increases in inequality. This 2004 study notes that if economic inequality remained at ’80s levels through the ’90s, prison rates would be lower by 10 to 20%.

Inequality may lead to more imprisonment because poorer people have greater incentives to commit crimes. But it can also lead to more imprisonment, and more policing, because those at the top feel increasingly distant from, and increasingly afraid of, those at the bottom. The police function as a system of social control.

In America, the fact that black people and other minorities are disproportionately poor makes it easier to ideologically justify inequality. The stereotypically non-white underclass can be pilloried as other, as criminal, and as deserving of regulation, segregation, and violence.

In every case, the point is that (disproportionately white) rich people are seen as having the right to do whatever they want with their wealth. And more, they feel justified in punishing anyone who, for a paranoid instant, they fear might want to take that wealth from them. Inequality enables, and is built on, violence.

Lion lives and black lives aren’t really in competition with each other. Rather, both are denigrated in favor of the lives, or even the whims, of wealthy, (often) white people. The powerful can use the world as their hunting grounds, metaphorically and literally. Everyone else is prey.

That’s the logic of privilege and the cruelty which movements like #BlackLivesMatter have been founded to challenge. But it’s not just black people who would benefit if that challenge is ultimately successful. If black lives mattered, Cecil the lion might not be dead either.