Every designer should know about this rentable font library

Free fonts are easy to find, whether through sites like Google Fonts or just the ones that come with your operating system. But these don’t always have the extended character sets or the nuanced kerning or the myriad of other details that go into higher priced fonts. Every dollar spent on carefully crafted type is a dollar well spent. Still, they can—justifiably—command prices in the hundreds.

Free fonts are easy to find, whether through sites like Google Fonts or just the ones that come with your operating system. But these don’t always have the extended character sets or the nuanced kerning or the myriad of other details that go into higher priced fonts. Every dollar spent on carefully crafted type is a dollar well spent. Still, they can—justifiably—command prices in the hundreds.

But do we want to collect and keep or just use? We may not quite be in a sharing economy yet, but we’re certainly in a “not owning” economy. With new streaming music and video apps popping up left and right and software-as-service coming to giants like Adobe’s Creative Cloud, it’s no surprise that having a collection of fonts collecting dust in your hard drive feels just as dated as flipping through a shelf of CDs. So when I saw Fontstand, a high-end, try-before-you-buy font service introduced on Twitter at the end of May, I enthusiastically clicked right in.

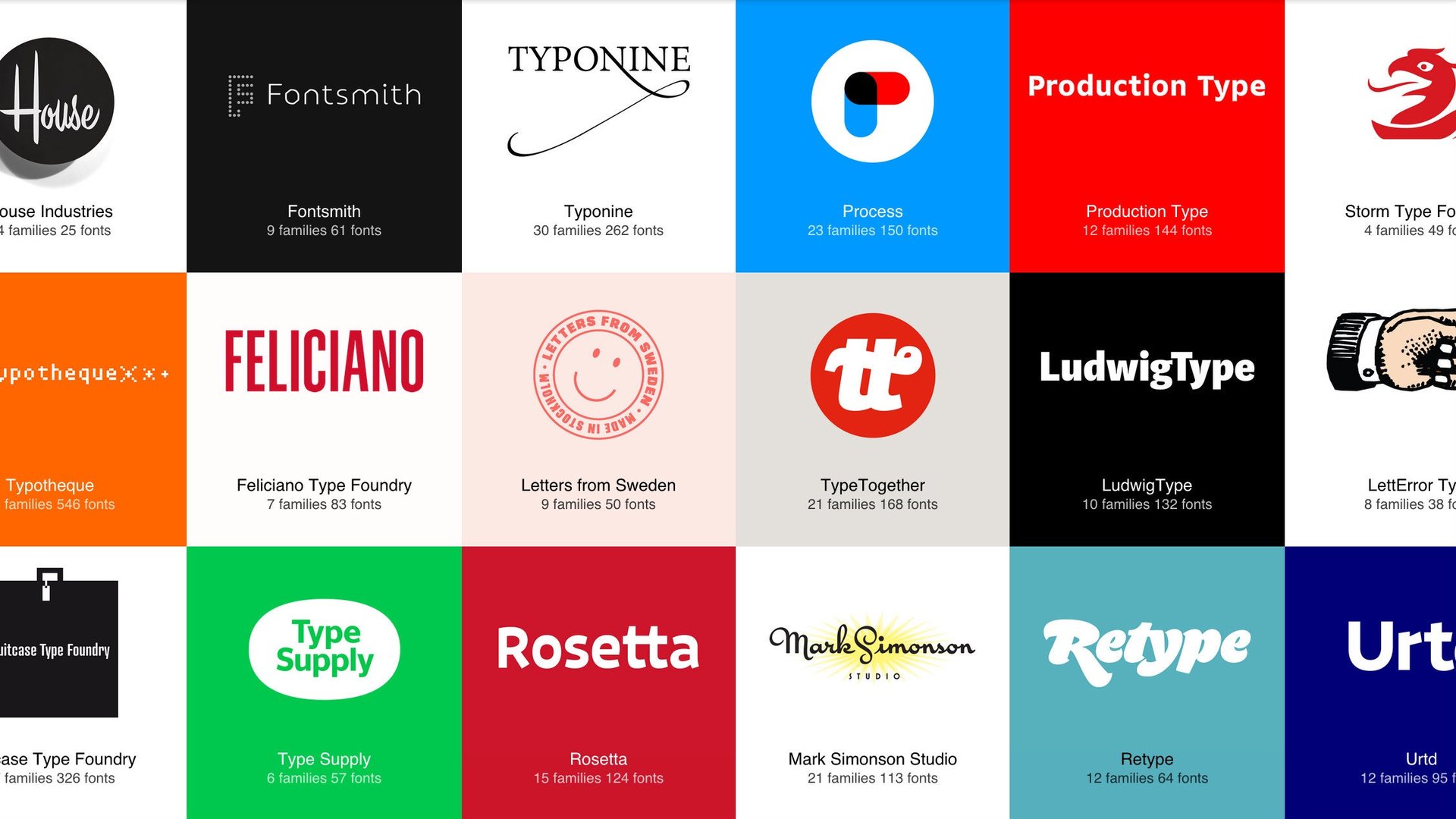

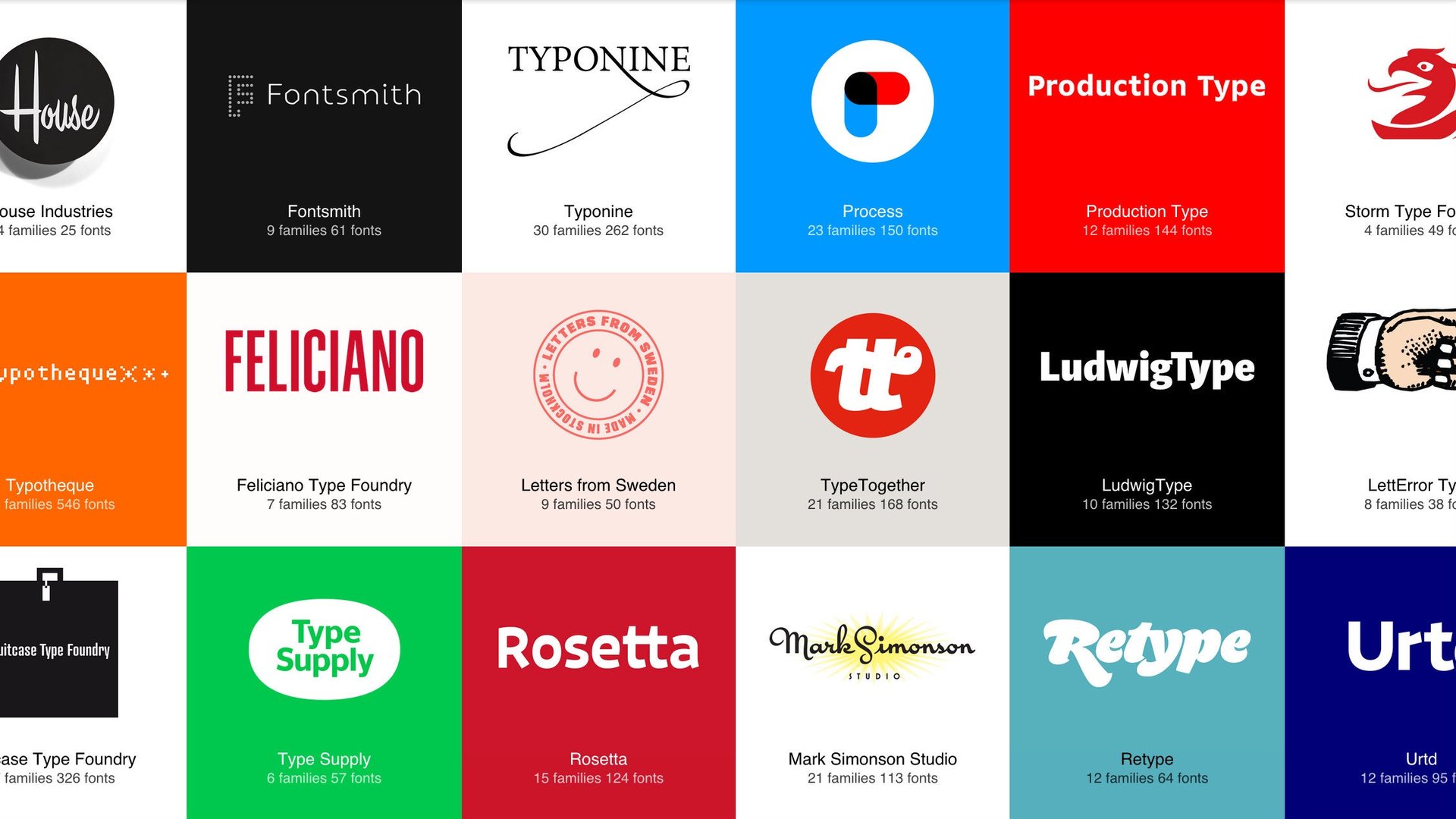

Fontstand is an elegant and colorful standalone app for Mac OS that seamlessly allows you to browse, try, and rent carefully crafted typefaces from type designers and independent foundries of the highest caliber. Now, instead of buying a complete font family, you can rent, say, just the extra bold italic if that’s all you need. Or rent the entire family for the limited time you might need it for a one-off job, saving hundreds of dollars. You can even share a font with a friend for an incremental increase in the rental fee. And any font you rent for 12 months is yours to keep.

Two years ago, Peter Bilak of Typotheque in The Netherlands teamed up with longtime friend and designer Andrej Krátky to work on a new business model for selling type. Previously, Bilak had experience rethinking content distribution with his excellent design magazine, Works That Work. “Andrej asked me what I thought about doing the same with fonts—making them available on reduced time-basis,” he explains. They brought Bilak’s former student Ondrej Jób to work on the interface and develop it into the gorgeous app it is today.

It’s fun to get your type from Fontstand. The rows of specimens are pure eye candy for type lovers and you can sample any of them for hour. As opposed to most free fonts you find with a web search, you have the confidence in knowing that those offered through Fontstand come complete with extensive OpenType features and glyph sets and have been kerned to perfection.

Fontstand’s creators are sensitive to the designer’s quandary of needing to experiment before buying. “As a type foundry,” says Bilak, “one of the most common questions asked by designers is to borrow the font before purchasing the license for it.”

He explains:

“This is understandable: ultimately, a foundry is asking them to pay hundreds of euros, while there is no guarantee that the fonts will fit their purpose. Many designers look for a way around this, such as searching illegal download sites to test whether the fonts are suitable for their work. They may not have ill intentions; they just cannot commit to buying the license before their client approves the project.”

After getting the go-ahead, the designers will often come to the foundry to legalize the licensing. Sometimes font clients complain about fonts, only to discover that they’re using an illegal version extracted from PDF, without proper kerning and spacing. Fontstand proposes a solution for easy testing fonts. Instead of asking foundries to discount them, we make fonts affordable by reducing their temporal scope of use.”

Tal Leming of Type Supply, one of the inaugural participating foundries, reiterates how cumbersome it was to handle requests for trials of his typefaces until he finally decided to just say no. (He wrote humorously about it on his site.) “I get lots of customers asking for trials, but it has been impractical for me to accommodate that,” he says. “Fontstand is an excellent solution. I’m also hoping that being able to try fonts will help designers explore new and different typefaces that they wouldn’t have seriously considered otherwise.”

Christian Schwartz and Paul Barnes of Commercial Type got on board early with Fontstand. “Paul and I both know, respect, and like Peter and thought Fontstand was a really interesting idea,” says Schwartz. “I think each foundry has different reasons for joining; we saw it as a way to reach audiences that we haven’t been reaching. In the bigger picture, I think the type market is ripe for innovation as far as platforms and font licensing are concerned, and it’s not in the best interest of type designers or users to cede the innovation to corporate bean counters that see type as a commodity and users as nothing more than a revenue stream.”

As with that indie musician you love listening to on Bandcamp, it feels good knowing your money is going directly to the artist, ensuring a sustainable economy for more quality type. As Bilak discussed in his talk on digital content licensing at TYPO Berlin this past May, piracy and creation go hand-in-hand. Napster upended the music industry and then iTunes made it easy to “do the right thing.” Apple Music and other streaming services are being challenged to remember that, for the most part, people are happy to pay for what they value. As Steve Jobs said in 2004, during the introduction of iTunes in Europe: “If you’re really going to compete with piracy, you have to offer a better product.”

“We also try to think of a fair price to compensate the makers,” Bilak continues. “Streaming services such as Spotify or Pandora offer millions of albums, but musicians don’t benefit from this at all. To earn even just the U.S. minimum wage ($1,160/month), an artist need to be streamed 4 million times a month! This is a completely unsustainable economic model, and may result in musicians looking for different jobs. Fontstand pays a fair price for every font sold back to its designers. It’s a win-win situation for the users and makers alike, and the only way to ensure that fonts continue being made.”

This post originally appeared on AIGA.