Smog-belching refrigerated trucks might soon emit harmless nitrogen instead

A lot of progress has been made with batteries designed to store electrical energy and drive engines, with consumer electric cars are gaining popularity for the cheap fuel and low emissions that make buyers happy and help countries meet clean air targets.

A lot of progress has been made with batteries designed to store electrical energy and drive engines, with consumer electric cars are gaining popularity for the cheap fuel and low emissions that make buyers happy and help countries meet clean air targets.

But a whole other world of dirty, outdated technology is still pumping carbon dioxide and other pollutants onto the streets. Called “auxiliary engines”, they generally run on diesel and drive the cooling system in refrigerated trucks that transport anything from milk to medicines. And they’re pretty much unregulated.

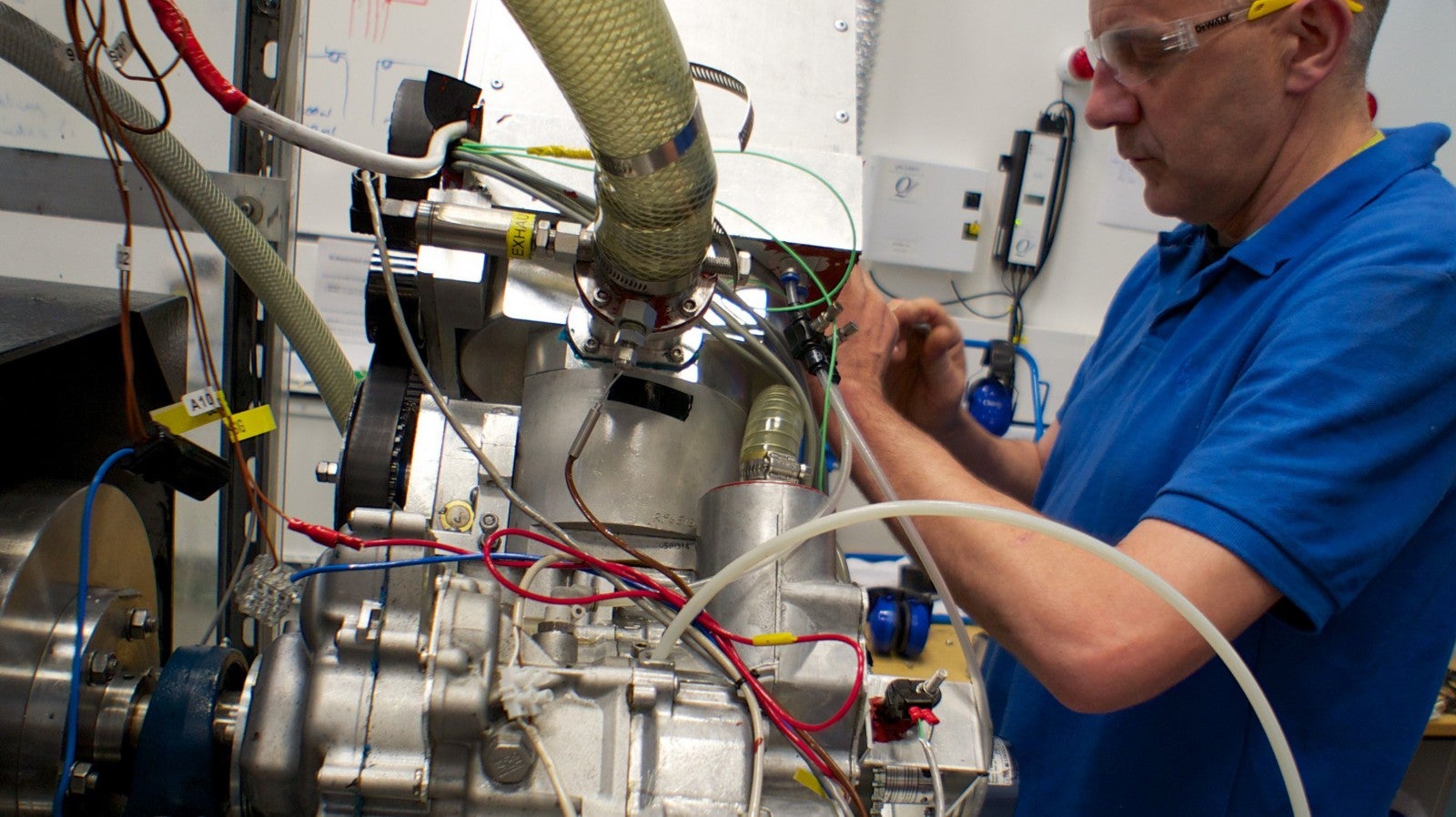

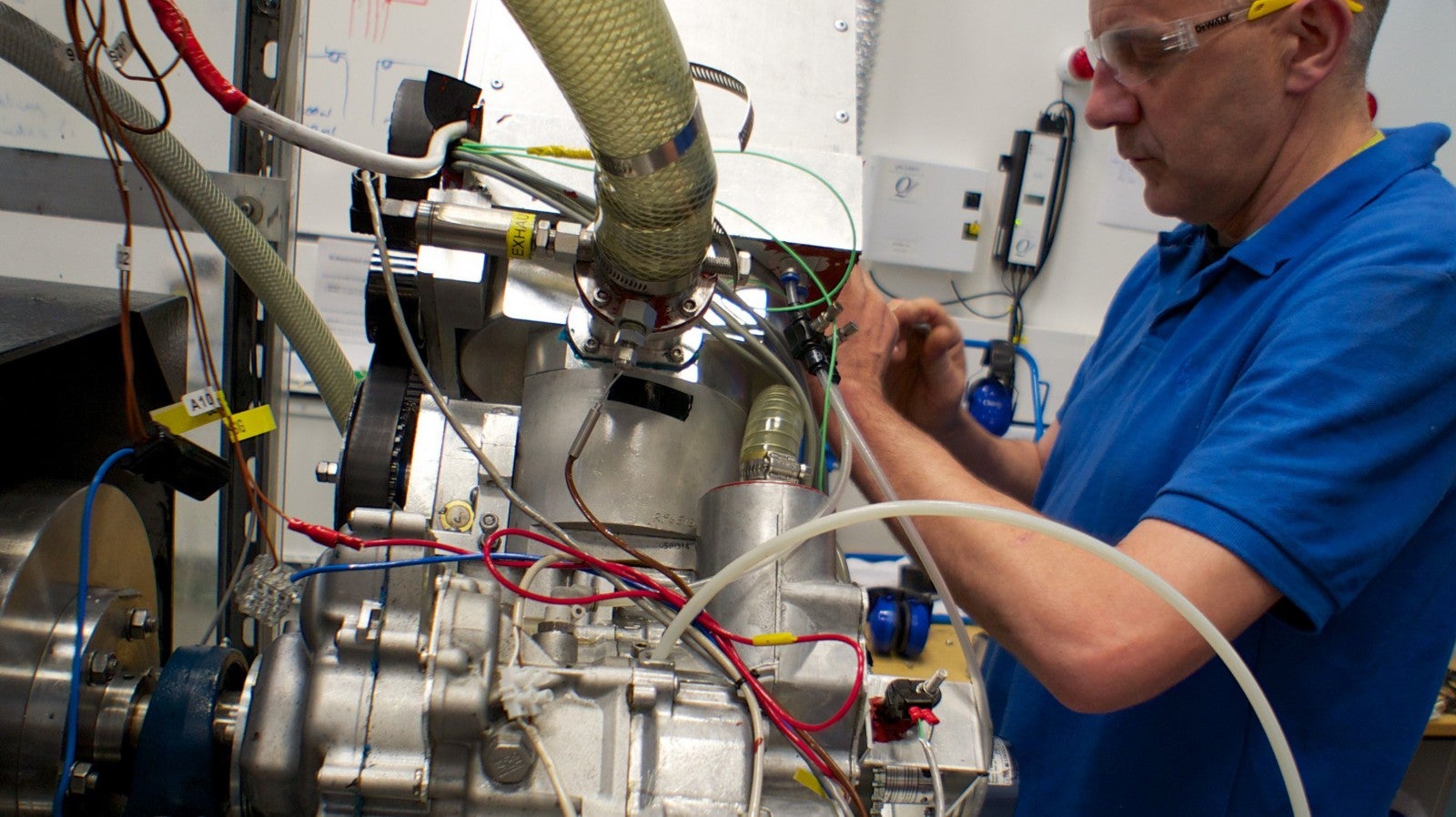

Dearman, a UK company, wants to solve the problem with a whole new type of engine that comes out of cryogenic technology—essentially using very, very cold temperatures to solve the pollution problem.

The Dearman engine uses nitrogen, which is stored as a liquid at -196 degrees celsius. This very cold liquid is in part used to do the cooling of, for example, a refrigerated compartment in a truck. But it also can drive an auxiliary engine that helps with processes like the pumping of a “heat exchange fluid.” The nitrogen would be allowed to warm from a liquid into a gas, expanding 710 times. This expansion then drives pistons in an engine, similar to those in, say, a steam engine.

The only emission from the process is nitrogen gas, which already makes up 78% of the earth’s atmosphere.

Could such an engine be used to power the truck itself? Toby Peters, Dearman’s chief executive, says while that might be possible, it would take so much infrastructure—roadside liquid nitrogen filling stations—that it isn’t really viable. Dearman’s trucks can carry the “liquid air” they need for cooling and still run in normal engines.

The development is timely. Demand for food is rapidly growing, while a focus on the food wasted is climbing up the agenda particularly in developed economies.

“The focus is always on increasing yield,” Mr Peters says. “But what we’re forgetting about…is that a lot of food, around about 30-40% of food, is lost post-harvest, before it gets to market, primarily because there’s no cold chain.”

This is particularly acute in the developing world. India loses around $13 billion worth of fresh food each year, the company estimates, while China throws away $15 billion worth of fresh produce.

India has 10,000 transport refrigeration units, and to get food moving from farm to city they need 160,000 new transport refrigeration units today, Peters says. Unsurprisingly, the company says its already in talks with commercial and governmental partners in India, the US and other parts of Asia.

The first food delivery vehicle with cryogenic cooling should be on the road in London by the Autumn, followed by small-scale trials in the UK, the Netherlands and Spain. By the end of next year, the company says, it’ll be doing trials in India and California.

If it works, it’ll be the realization of a lifelong dream for Peter Dearman, the company’s founder and an inveterate inventor who has been seeking applications for liquid nitrogen for the past fifty years.