The white dress is a fantasy the wedding industry spun to make us spend more

“Tradition!” My German grandmother picked out the word in her careful, almost-English accent, eyebrows raised. There’s nothing traditional about these huge weddings, she said. When she and her husband married, in December 1942 in London, they walked home from the service with their parents and had lunch; that was their tradition.

“Tradition!” My German grandmother picked out the word in her careful, almost-English accent, eyebrows raised. There’s nothing traditional about these huge weddings, she said. When she and her husband married, in December 1942 in London, they walked home from the service with their parents and had lunch; that was their tradition.

It wasn’t an entirely uncommon one, either. But it feels completely divorced from what we consider today to be traditional: guests by the hundreds, expensive rings, multi-tiered cakes, and of course The Dress. More than anything, it’s those strips of cloth that decide whether a wedding is the epitome of “tradition,” namely white.

Most people think that Western brides wear white as the legacy of a time when the purity of a maiden bride needed to be displayed. With marriages today tending to symbolize firm commitment rather than first intimacy, that seems out of step with the modern world. And still, the popularity of white abides.

When I came to choose a wedding outfit, white was certainly not the only option on the table. I considered green. I toyed with red. My mother had married in a gold suit. And yet, after running the gauntlet of specialist boutiques, vintage shops, tailors and department stores, what I ended up in was—you guessed it—a cascade of gleaming, pure-as-the-driven-snow white.

Edwina Ehrman has heard this story many times.

Ehrman, who curates fashion and textiles for the Victoria & Albert museum in London, collected stories as well as frocks when she put together a major exhibition of wedding dresses for the museum last year.

“I have asked people recently why they wore white,” she said. Many, she said, tell her something along the lines of, “’I had no intention of wearing a white dress, but I thought I’d just try one on.’ And when they tried it on they felt—and they all used the same word—they felt transformed. They suddenly felt like a bride.”

In doing so, notes Ehrman, they—or rather, we—perpetuate a tradition that has been shaped more by fiction, and by the media, than by reality.

Yes, some brides throughout history have selected white, but according to Ehrman, it didn’t become a common choice until the 18th century. And when it did, it was as a symbol of status.

“White was a very, very expensive colour, and most people couldn’t afford to have a white dress in their wardrobe,” she said. “So it was a special colour, a prestigious colour,” and became popular for wedding dresses alongside fabrics woven with metal threads, like gold and silver.

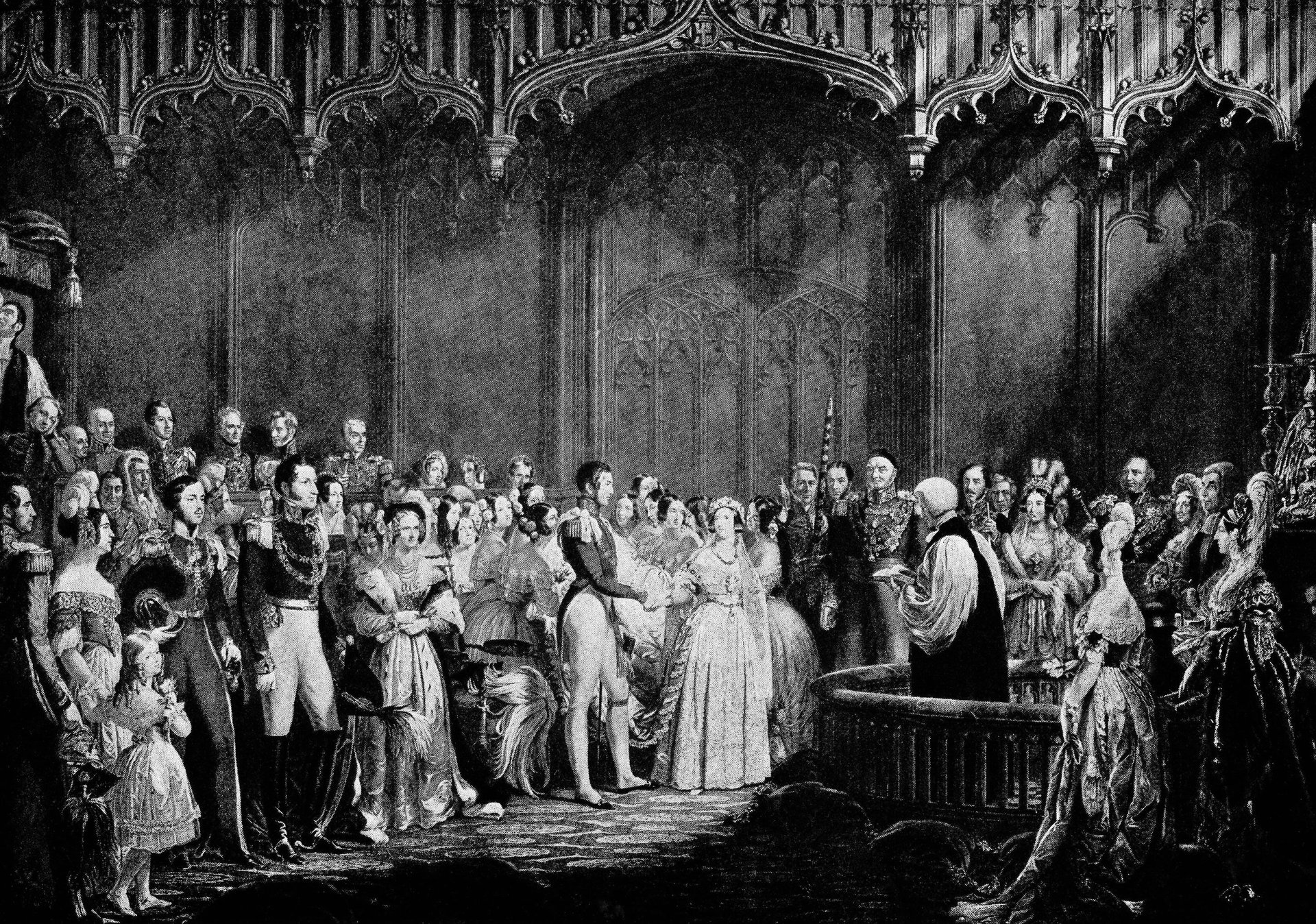

Queen Victoria’s decision to wear white when she married Albert in 1840 was unusual, and it heralded a string of royal princesses following in her footsteps. Only after Victoria made it popular, Ehrman said, did the word “chaste” begin to arise in reference to the white wedding dress.

While white soon became the principle color women aspired to, other colors, like blue, continued to be worn by those for whom a white dress—in an era when all clothes were re-worn, altered, and worn again—was just too impractical.

“If white had been associated with chastity and virginity, which was so prized among the middle and upper classes in the Victorian period, these women would have gone to every length possible to have worn a white dress,” Ehrman said. “They would not have compromised on a blue dress. And yet many, many happily wore a colored dress.”

The 1920s saw more gold, shell pink, and silver at weddings than blancmange, according to Ehrman. And icons of timeless style have often eschewed snowy lace for something altogether more cool.

“There’s this dialogue, constantly, between white and color,” Ehrman said.

White remains expensive, even in an era of disposable clothing. It’s still impractical, decadent, and therefore unusual in everyday life. In that sense, the intimidating industry that has grown up around The Dress gets at least a few things right.

For starters, that white = expensive equation ain’t wrong. The average cost of a wedding dress is £1,340 (about $2,075), according to Brides magazine. And if you plan to find one cheaper than that, take heed: some people will make you feel very bad about it.

My own journey started in a wedding dress shop in Islington, north London, where I and a friend tried on some beautiful dresses, laughed aloud at the prices, and marveled at the way I looked so weirdly “like a bride.”

Later, I looked online and found a knockoff of the designer gown for just £39 including shipping. I knew it would not be the same dress, but I bought it—encouraged by other friends—just to see. When it arrived, I had to admit it: this dress came nowhere close to the original.

Over the next few weeks I visited other wedding dress shops, each time drawn by the image and driven away by the price, the impracticality, the idea of wearing something so beautifully boring, so acceptably self-indulgent. I went to vintage shops, where more than one person expressed their opprobrium that I was even considering wearing a cheap dress, purchased online, for my wedding. I bought another, more expensive but less weddingy dress online (eventually returning both). I went to Selfridges. I went to charity shops.

Getting married involves a lot of being told what you must do. Change your name. Look more beautiful than ever before, preferably in a £1,000 dress. Be considerate in devising your invitation list, your seating chart, and the accommodations available to your guests. And, simultaneously, have the time of your life.

The day of our wedding dawned scorching hot after a night of thunderstorms. I wore white, a resplendent dress fit for no one else but a bride, bought for £50 from a charity shop and altered to fit by a tailor for the same amount. (While he pinned it, another customer expressed her unsolicited opinion: “That’ll be difficult to shorten. That’s a lot of material. A looooot of material.”)

Our white weddings are what Baudrillard called simulacra: copies of something for which there is no original. They are enticing visions, though, and so we keep fulfilling them, staying faithful to a tradition rooted in little more than what we have willed it to be.