The perfect storm is heading toward the debt market

In the markets, it’s starting to look like the 100-year wave is just over the horizon and I’m left with a sensation that the question is not “if” it is coming but “when.”

In the markets, it’s starting to look like the 100-year wave is just over the horizon and I’m left with a sensation that the question is not “if” it is coming but “when.”

For the past couple of years something big has changed in the markets, leaving many market participants feeling like up is down and down up. All of the sudden the bond market is starting to behave more like the stock market, at least in the eyes of investors. It’s like that moment in the movie The Perfect Storm when Mark Wahlberg and George Clooney decide to weather the storm and the conditions for fishing are almost eerily good. Just like the many oh-so-good years in the bond markets—with some funds having returns well over 100%.

Trying to investigate this new fad in the markets, I’ve talked to many hedge fund managers, researchers, bond traders and other market participants. As the conditions seem to get better and better, it is starting to feel like we might be heading into some kind of never-before-seen storm system.

Perfect storm

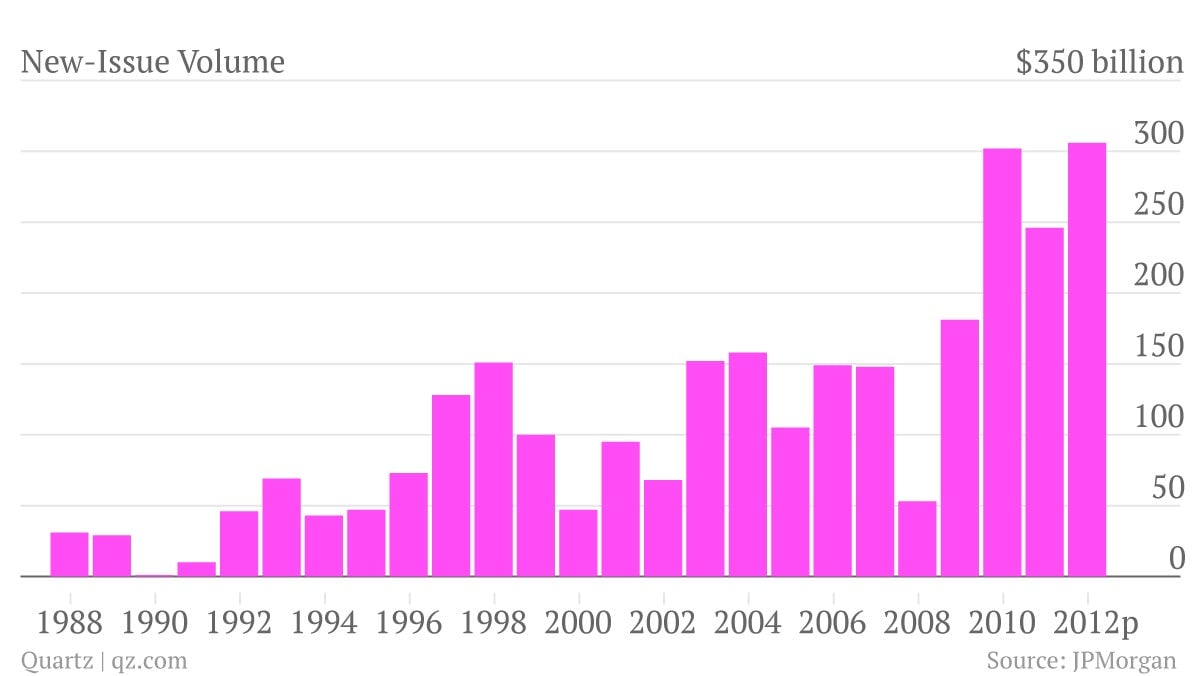

For the last few years, the story in the equity markets has developed into a debt story. Most companies have issued new debt; a dramatic increase in debt issuance is expected. Even before 2012 ended, it was clear that the amount of debt issued was at an all-time high. As of October, the amount of new debt issued had already reached $306 billion (see chart).

According to Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), the issuance of new corporate debt for US corporations reached a new all time high in 2012. In total, $1.3 trillion in corporate debt was issued, above the previous record set in 2007, when $1.1 trillion in debt was issued.

But the debt party, or what later might feel like a hangover, is not over yet.

The magazine Institutional Investor has estimated that European companies need to refinance $8.6 trillion of debt and an additional $1.9 to $ 2.3 trillion of debt for growth by 2016:

In our view, these factors; the current Euro Zone crisis, a soft U.S. economic recovery and the prospect of slowing Chinese growth, raise the prospect of a perfect storm for credit markets.

Fed’s worried

It’s not only the issuance that is at a record level but also yields, the interest demanded by the market to lend money, which are at record lows. This means that the so-called “high-yield bonds,” don’t yield very high at all. In the start of 2013, the average yield for a US high-yield bonds, which are sometimes referred to as junk bonds, was below 6% for the first time ever.

Recently, US Federal Reserve officials voiced increased concern that the low interest rates would create overheating in many markets—including high-yield bonds: “Prices of assets such as bonds, agricultural land, and high-yield and leveraged loans are at historically high levels,” Kansas City Fed President Esther George said in a speech, according to Bloomberg. “We must not ignore the possibility that the low-interest rate policy may be creating incentives that lead to future financial imbalances.”

Dumb money

The problem with the high-yield market is found in its structure, how the bonds are traded and who is buying them.

In most cases, these types of debt instruments are traded broker-to-broker in the so called OTC, over the counter, market. This means that if you are looking to buy an asset, you would normally call up a broker to get a price quote. In many ways this means that the way high-yield bonds are traded in 2012 is not very different from how high-yield bonds were traded in 1985.

This is exactly the opposite of the situation in the stock market, where it is obvious to anyone what the price of an asset is – you just check the quote. The information is right there. In the bond market, it is still a one-to-one market, it is really only the traders that know what the prices are.

Albeit some systems have created a sliver of modernity in the bond market, namely the bond trading platform run by the investment firm BlackRock. Due to the low level of transparency, the market is still a highly lucrative for the brokers.

In a world where stock brokers are almost non-existent, the bond broker is still making the big bucks. This gives the big banks and brokerages a very high incentive to keep churning out debt, before the ride stops.

The money is just too good. Just look to Norway’s biggest brokerage, DNB Markets. It recently published quarterly earnings, revealing that “income from international bond holdings” went from a small loss a year ago to gains of $126 million in the latest quarter. That gain represented about half of the bottom line for the brokerage.

So who’s buying the debt instruments? Well, increasingly, it’s the unsophisticated investors—the so-call dumb money—who are adding money to the pot.

A few years back we were told by several brokerages that all their high net worth customers were rushing into bonds. Now it’s the rest of the investors.

Several people I’ve talked to are now waiting for that moment. You know that moment. When you, as a financial professional, enter a taxi, meet a financially illiterate relative or a hairdresser and that question pops up: “So, what do you think about those high-yield bonds?”

That’s the moment. The moment when you sell it all and go short.

Blow up risks

How bad a downturn might be in numbers is really anybody’s guess, but how it might happen is probably a little easier to figure out. The bond market is actually nothing close to the stock market in the way it functions. The primary problem is the liquidity. Or lack thereof.

High-yield bonds, especially those issued by smaller companies, are simply not traded very much. While a stock might be traded thousands of times in a day, creating an accurate market price, a bond might be untraded for days, weeks, months, and in some cases during the entire lifetime of the bond.

Regardless of this, the bonds get a market price on a daily basis, based on a number of factors. This works great when the market’s doing well. The charts are smooth and everybody makes money.

But the blowup risks are massive. Consider this example presented to me by a fund manager:

Most bond investors don’t buy the bonds directly, but do so via high-yield bond funds. These have offered tremendous returns for years.

These funds have a cash buffer. This is to make it possible for investors to exit their investment without the fund having to liquidate a not-so-liquid bond position.

Let’s say an event, on the macro level, causes a few investors to dump the fund at the same time. This would deplete the cash. The fund now needs to liquidate some of its bonds. But at what price? Some of these bonds might be traded on an infrequent basis. So what is the price that is quoted?

The price will probably be significantly lower than the previous “market” price. Let’s imagine that a number of these funds suffer similar draw downs and are forced to sell at the same time. This will naturally cause prices to drop. This price drop will most likely cause other investors to try and get out.

And thus: you have a run on the fund.

Perhaps it’s not smart to be out fishing for yield right now. Perhaps it’s better to head back to shore and brace for a storm.

Because it really is calm now…