Why the new BlackBerry 10 phones won’t stop RIM’s dramatic contraction

Tomorrow (Jan. 30), Research in Motion announces a handful of new BlackBerry 10 phones. The world already knows what they will look like and how they’ll function, thanks to copious leaks. But that won’t lessen enthusiasm for a slick new alternative to the mobile duopolists, Apple’s iPhone and Google’s Android. And doubtless it will inspire yet more breathless accountsof RIM’s resurgence.

Tomorrow (Jan. 30), Research in Motion announces a handful of new BlackBerry 10 phones. The world already knows what they will look like and how they’ll function, thanks to copious leaks. But that won’t lessen enthusiasm for a slick new alternative to the mobile duopolists, Apple’s iPhone and Google’s Android. And doubtless it will inspire yet more breathless accountsof RIM’s resurgence.

But the release of the devices—however excellent they are—is mostly a distraction from the fact that RIM could be in terminal decline. Before the story of its comeback gains any more momentum, it’s worth taking stock of its liabilities.

1. The new hardware and software in RIM’s BlackBerry 10 phone is spectacular, but in some respects irrelevant.

RIM is so late to the game of creating a mobile phone as powerful and versatile as an iPhone or an Android phone, and has lost so much market share since its peak in 2010, that by all accounts the best it can hope to accomplish in the future is to compete with Windows Phone for a (distant) third place in the smartphone market.

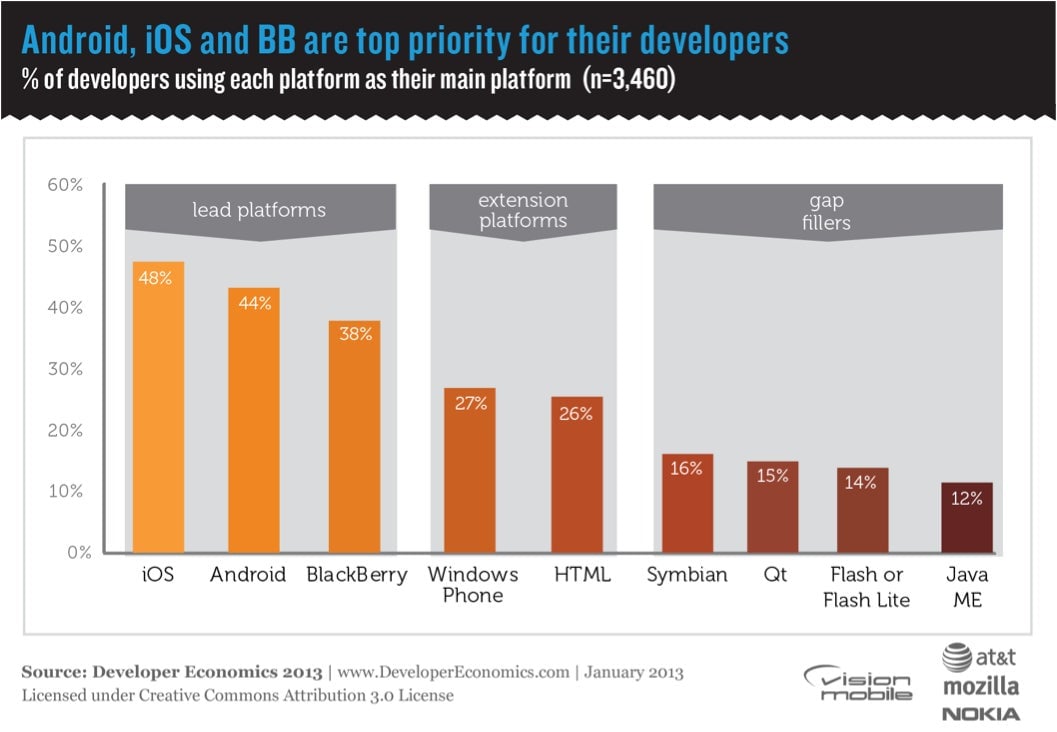

The good news for RIM is that while it lacks Microsoft’s resources—and therefore ability to lose money on the business of mobile almost indefinitely—it has the one thing on its side that could allow it to beat Windows Phone, anyway: the goodwill of mobile developers. Here’s the results from a survey of 3,460 mobile developers, conducted by the mobile ecosystem analysts at Vision Mobile.

Because of the importance of apps to a smartphone’s user experience, and the dependence of any smartphone company on the countless developers who create those apps, the mobile phone market is now winner-take-all, or nearly so. As Andreas Constantinou, managing director of Vision Mobile told me in November, “It’s impossible for anyone to compete with the duopoly of Google and Apple.” What he meant is that people demand that their phones run the apps that they want, but developers won’t build apps for a platform unless there is a critical mass of users. This is the fundamental reason that even Windows Phone, with all Microsoft’s resources, is barely making inroads against Android and iPhone.

RIM is well aware of the importance of apps, which is why the company is aggressively courting developers, even promising them a minimum of $10,000 in revenue. RIM claims that when it launches, BlackBerry 10 will have a library of 70,000 apps.

Unfortunately, that’s still less than 10% of the more than 700,000 apps available for iPhone and Android, and it’s the primary reason why, no matter how good the hardware and software in the new BlackBerry might be, it’s unlikely to capture market share from Android or iPhone. Even if RIM managed to create the best user experience out of any of the major smartphone platforms, there is little enough room for innovation that it can’t be more than a gloss on existing user experiences.

While it’s true that RIM only needs the “right” apps and not the biggest library, the fact remains that its developer community is much smaller that that of Apple’s iOS or Android. Given how scarce mobile developers are already, finding programmers who know a platform is a major barrier for enterprise customers looking to create custom apps. Web-based HTML5 technology and the (apparently quite fast) web browser in the Blackberry 10 phone could be saving graces for the device, except that users are apparently still quite addicted to the native app experience for everything except for news consumption and a handful of other edge cases.

If RIM had moved faster, it could have exploited its stickiness to hold on to millions more customers, but instead it has seen huge drops in market share as users lost patience while waiting for BlackBerry 10. BlackBerry’s share of the smartphone market in the US was 1.1% in December. Globally, BlackBerry’s market share is 4.3%.

2. The “network effects” of RIM’s free BlackBerry Messenger service, which kept the phone popular in some markets, no longer apply.

For years, RIM’s popularity among young people in countries like Indonesia was due to its BlackBerry Messenger service, which was the first to allow users to text each other for free, and thus get around the usurious fees for text messages charged by mobile carriers. But Android and iPhone can accomplish free messaging via apps, and users are taking advantage of that capability, as evidenced by the enormous popularity of apps like WeChat and Facebook Messenger.

In September 2012, Android became a more popular mobile OS than BlackBerry in Indonesia, which had previously been the biggest market in which it still held sway. Once that tipping point was crossed, network effects that were preserving RIM’s lead started to work against it. Now, if you want to send free messages to friends in certain countries, you’re better off switching to one of the cheap Android handsets that have been flooding the world of late.

In November, BlackBerry saw huge losses in key markets in which it had previously had higher-than-average market share, including the UK—down by half, to 9%—and in Brazil, Spain and France.

3. Enterprise customers that need control and security are no longer locked into the BlackBerry ecosystem.

It’s not unlikely that US President Barack Obama, a long-time fan of BlackBerry, will be an early adopter of the BlackBerry 10 phone. RIM is touting the fact that on the day it launches, BlackBerry 10 will be certified by the US federal government as suitable for use by government agencies.

Yet customers like the Department of Homeland Security are already abandoning BlackBerry, and RIM’s formerly stalwart customers in the legal and finance industry appear to be following suit. The larger trend of BYOD, or “bring your own device [to work],” in which businesses and even governments are forced to accommodate the mobile devices that users themselves purchase, is hastening the standardization of large organizations on iPhone and Android devices. Even BlackBerry has been forced to admit this sea change, making its own software for managing BlackBerry devices compatible with iPhone and Android devices.

Both Apple and Google have made their operating systems compatible with business environments by making their operating systems more secure. Independent of Google, Samsung has created its “SAFE” technology to make its Android devices enterprise-ready, and, in another direct challenge to RIM, Samsung also recently took a strategic stake in Canadian mobile enterprise security company Fixmo.

In a development that would have been inconceivable just two years ago, more iPhones are now being used by enterprise clients than BlackBerries.

4. The new BlackBerry 10 OS is for high-end devices, but the bulk of RIM’s customer base is buyers of low-end BlackBerry phones in the developing world.

As of the third quarter of 2012, RIM had 79 million active subscribers worldwide, down—for the first time ever—from 80 million subscribers in the previous quarter. RIM’s business in the US, Canada and the UK is dwarfed by its sales in developing countries. (RIM is still quite popular in, for example, Nigeria and Venezuela.) These are precisely the markets in which BlackBerry has seen its most rapid drops in market share, which does not bode well for the company’s fourth quarter results.

RIM’s BlackBerry 10 operating system, which requires high-end hardware, will not be available on the cheaper devices that are the backbone of RIM’s customer base, and probably won’t reach those devices for years. Which is yet another way RIM has effectively abandoned these customers to cheap Android smartphones.

RIM is going to get a lot smaller, even if it succeeds.

If BlackBerry 10 is as good as all the leaks suggest, it’s possible that RIM will be competitive enough with Windows Phone to capture a share of the market for high-end phones on the order of its current global market share, or something less than 5%. As RIM focuses its product efforts on the developed world, it seems to be trying on an Apple-like strategy of ceding market share while concentrating on margins, and therefore revenue. It’s possible that RIM could recapture some customers in the US federal government, and while it could be problematic for the company’s margins, RIM’s CEO has also floated the possibility of licensing the BlackBerry 10 operating system to other hardware manufacturers.

The larger problem RIM faces is that third place in the smartphone race is going to be the most difficult position to hold onto. In addition to Windows Phone, an increasingly crowded field of last-place competitors includes upstarts like Jolla, Samsung’s Tizen, and open-source efforts like Mozilla Phone. And with RIM shedding customers in emerging markets, it’s not clear that BlackBerry 10 will allow it do anything more than hang onto the minority of its existing customers who are already on high-end devices. If that’s the case, RIM’s global market share could soon be as little as 1% or less, making the company little more than a curiosity, and eventually leading to an exodous of developers to other platforms. And without developers, no modern smartphone manufacturer can survive.