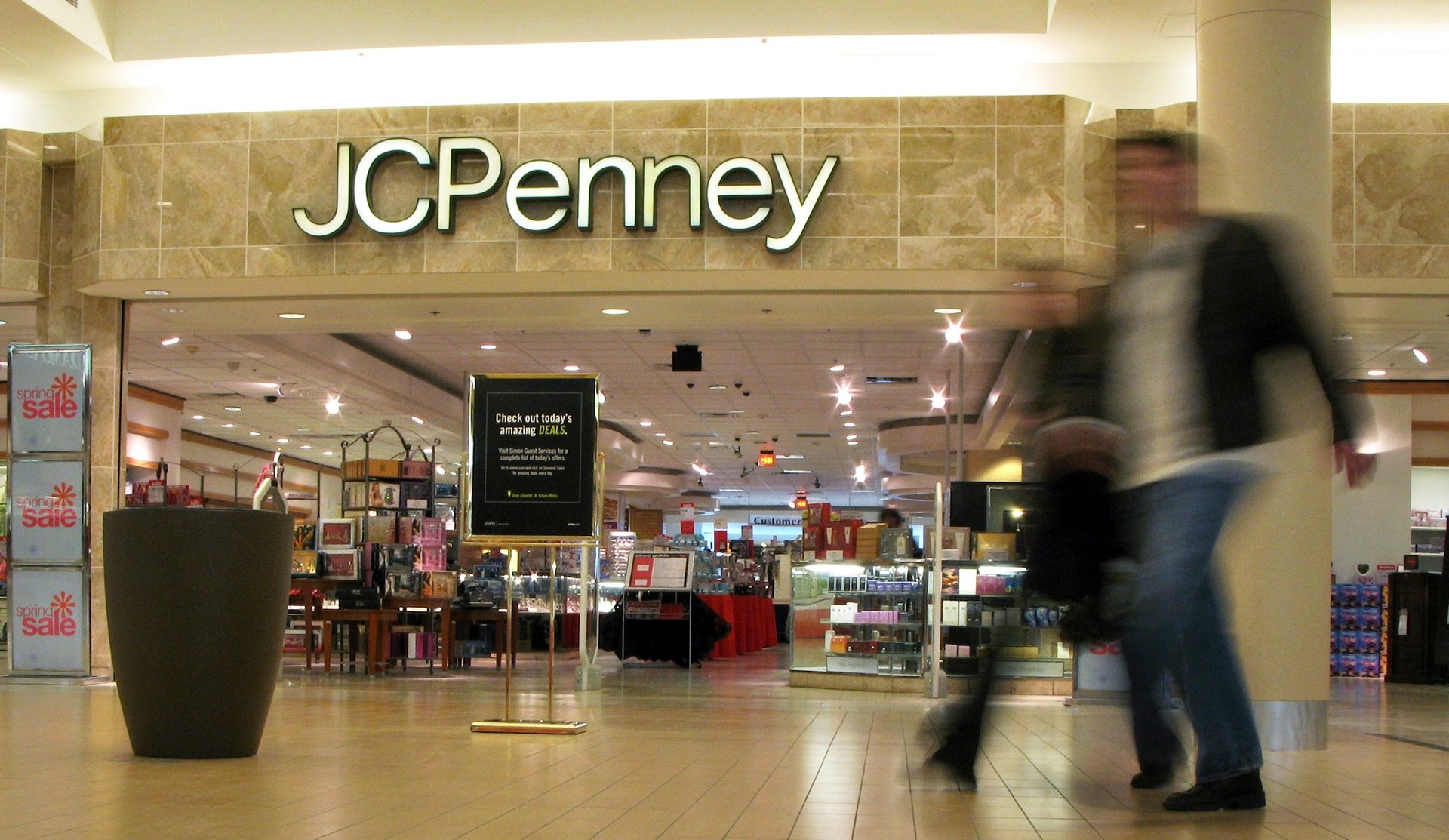

After a year of tanking sales, JC Penney learns that shoppers actually like retail mind games

JC Penney is doing an about-face. When Ron Johnson—the mastermind behind Apple’s wildly successful retail stores—took over as JC Penney’s CEO in 2011, he decided that, in an era of ubiquitous online pricing information, ”customers will not pay literally a penny more than the true value of the product.” Arguing that shoppers would prefer permanently lower prices than waiting around for sales, Johnson made his first big move by marking down the company’s merchandise by at least 40%.

JC Penney is doing an about-face. When Ron Johnson—the mastermind behind Apple’s wildly successful retail stores—took over as JC Penney’s CEO in 2011, he decided that, in an era of ubiquitous online pricing information, ”customers will not pay literally a penny more than the true value of the product.” Arguing that shoppers would prefer permanently lower prices than waiting around for sales, Johnson made his first big move by marking down the company’s merchandise by at least 40%.

To be sure, the company’s stores were struggling before Johnson came in. From 2006 to 2011, “J. C. Penney has had the worst performance among peers,” wrote Barclays Capital’s Robert S. Drbul, via the New York Times. But Johnson took the company from a period of gentle decline to downright free-fall. The company reported a 26.1% decline in comparable-store sales in the third quarter of last year, while Macy’s reported a 3.7% increase in same-store sales for the same quarter.

Now—one year after reinventing JC Penney to compete in the digital age—the company is bringing back discount sales and coupons to lure back shoppers. As Johnson explained the decision to the Associated Press, “We made changes and we learned an incredible amount. That is what’s informing our tactics as we go forward.”

So why then is the 121-year-old company backtracking? For one thing, flash sales continue to have powerful psychological effects, said Jeff Galak, a professor of marketing at Carnegie Mellon, in 2010. Short-term sales make shoppers feel lucky and exclusive, Galak told the Wall Street Journal. He added that merely setting prices with a “9” at the end (whether it’s $9.99 or $49.99) created the impression among customers that they were getting a deal. “People tend to be cognitive misers,” he said. “You don’t have time to process every single digit that comes your way, so you use the left digit.”

Then there’s the bargain-structuring—something the old JC Penney used to do a lot. Dan Ariely, a behavioral economist who studies consumer decision-making, has documented how conditional coupons (pdf)—for example, “buy one, get one free”—prompt shoppers to unconsciously set concrete shopping goals close to or just above the stated conditions.

That suggests that shopper mentality is unlikely to have changed all that much. And that’s good news for the department store. Whether the brand still has enough of its old reputation to win them back, though—that’s the question that will fill the sidebars of marketing textbooks for a while to come.