Scientists want to rethink bans on tinkering with human embryo DNA

Tweaking human embryo DNA is no longer a theoretical prospect. Rapid advances in “genome editing” technology mean that scientists can now efficiently and precisely modify DNA.

Tweaking human embryo DNA is no longer a theoretical prospect. Rapid advances in “genome editing” technology mean that scientists can now efficiently and precisely modify DNA.

The only thing stopping them are a range of laws, guidelines and other restrictions, which an international group of experts says need to be reconsidered.

Editing human embryos’ DNA has long been seen as an ethical red line. Without proper oversight, the science could create designer babies and eugenics horror stories.

But the Hinxton group, an international network of stem cell researchers, bioethicists and policy experts, has joined calls for a debate on the subject. In a statement issued this week (pdf), the group said that genetically modifying human embryos is of “tremendous value” to research.

The Hinxton group added that, though it did not currently support allowing GM embryos to be born, there could be “morally acceptable uses of this technology in human reproduction”.

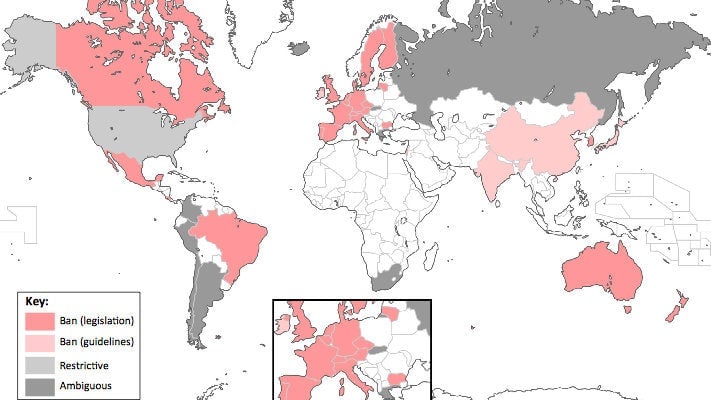

Most developed countries have some form of legislation to prohibit human embryo genetic modification. The map below, taken from a paper on the socioethical implications of GM embryos, shows the restrictions in place across 39 surveyed countries.

But legislation is not universal, and earlier this year scientists in China published the world’s first scientific paper on altering the DNA of human embryos. Robin Lovell-Badge, a member of the Hinxton Group and scientist at the Francis Crick Institute, tells Quartz that the West should not “shut the door” to genetically modified embryos. “By doing that, you make people who are doing stuff that’s relevant, do so behind closed doors,” he says.

Genetic modification of embryos could lead to several health benefits in the long run. It could improve IVF treatment, correct genetic defects such as Huntington’s Disease, and create humans with in-built resistance to certain diseases.

“You could think about making disease resistance for a variety of infectious diseases, even influenza,” Lovell-Badge tells Quartz. “When you talk to people and say, ‘Would you like to have children who are resistant to a range of different diseases,’ most people would think, ‘Well maybe that’s not such a bad idea.’ That’s the acceptable form of enhancement.”

But several scientists have warned that attempts to genetically engineer human embryos could lead to unacceptable uses of the technology. In March, a group of US scientist voiced their opposition in an article for Nature, saying:

In our view, genome editing in human embryos using current technologies could have unpredictable effects on future generations. This makes it dangerous and ethically unacceptable. Such research could be exploited for non-therapeutic modifications.

International legislation is unfeasible, and so even if scientists operate under clear guidelines, there’s always the danger that researchers in another country could misuse their work.

There’s also a risk that genetic modification of humans could create a class of wealthy superhumans, who are impervious to the diseases that blight poorer people.

“Is this just going to be technology for rich people in rich countries? The people who would benefit most from disease resistance would be people in pooper countries in sub-Saharan Africa, where HIV is prevalent, and they are the ones least likely to afford it. I can’t solve that,” says Lovell-Badge.

Genetic modification could be misused to create beautiful offspring, though Lovell-Badge says he finds this “pointless” rather than immoral.

“I think it’s a bit of a waste of the technology but I don’t have a real ethical problem against it,” he says. “I just think it would be a trivial use.”

Others may well disagree, but these debates no longer belong in the realm of science fiction.