How companies are using LEGOs to unlock talent employees didn’t know they had

This summer, Cambridge University announced a search for a “LEGO Professor of Play, Education, and Learning.” With the support of £4 million ($6.1 million) from the LEGO Foundation, the new professor would lead an entire research department dedicated to examining play.

This summer, Cambridge University announced a search for a “LEGO Professor of Play, Education, and Learning.” With the support of £4 million ($6.1 million) from the LEGO Foundation, the new professor would lead an entire research department dedicated to examining play.

This is an endeavor that Robert Rasmussen knows all about.

In the late ‘90s, he was asked by then-LEGO Group CEO, Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, to explore how LEGO bricks could help a company improve its strategic planning, communication, and creative thinking. Rasmussen, a former math teacher and school principal, was already part of the LEGO family, leading product development for LEGO’s education division, which focused solely on children. What started as a project to be completed in his spare time became a defining career shift for Rasmussen, who is known as the architect of the LEGO Serious Play (LSP) methodology.

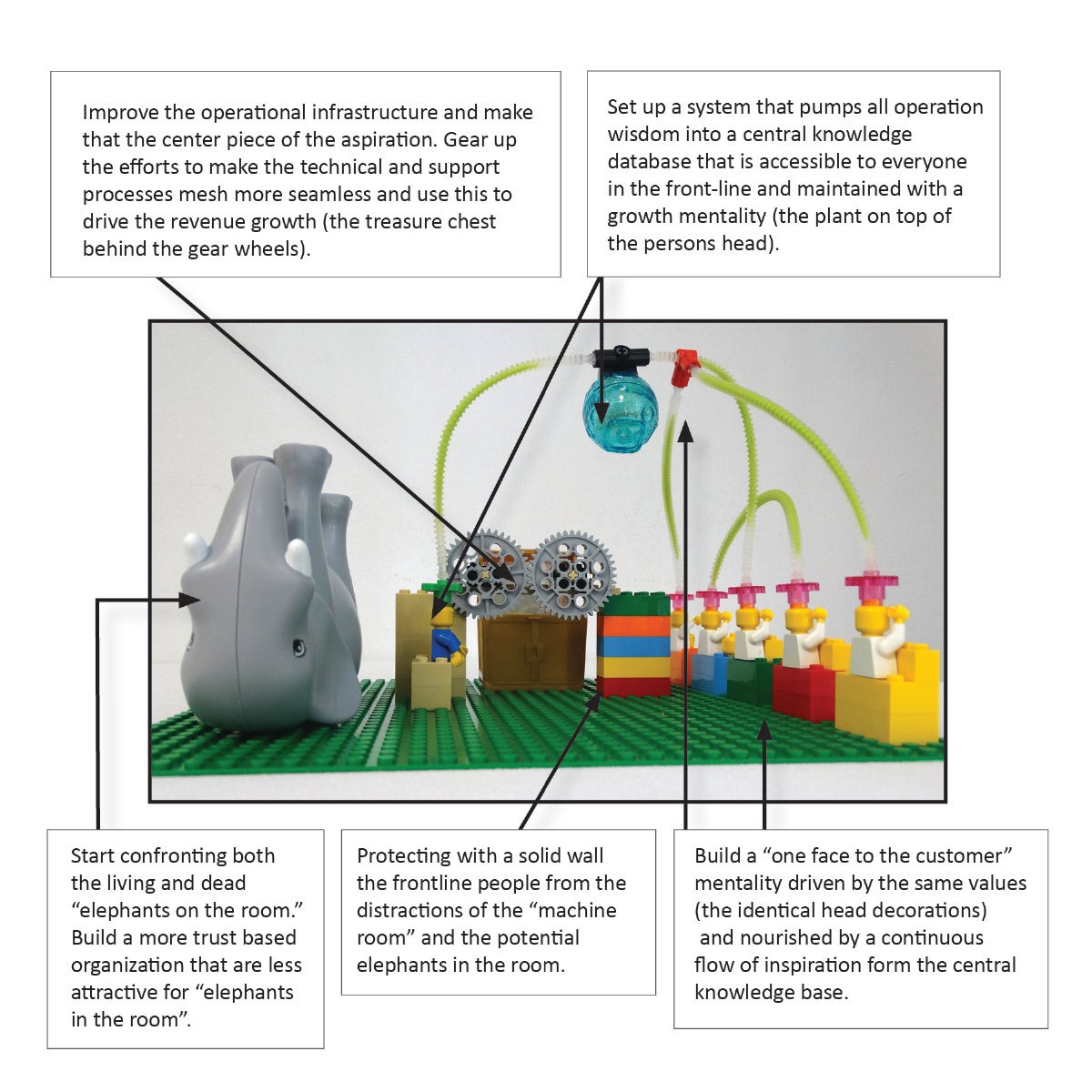

“It’s an engine. It’s like a language. It’s a technique without content,” Rasmussen told Quartz, who likens the method to an operating system. “It is the facilitator who asks a question, then the participants build the answer to that question using LEGO bricks, using them metaphorically to add meaning,” he said.

Sessions can start off with a question such as, “Name one challenge that is preventing growth in your company and build your answer with LEGOs. You have four minutes. Go.” Facilitators support this process by knowing the right questions to ask and helping participants draw out the meaning from their answers made out of bricks.

Just as LEGO bricks can be used to build a representation of virtually anything, the LSP method can be applied to any company objective, whether it’s solving a media crisis or brainstorming ways to transform your current business model. Rasmussen has been invited to guide companies that are looking to solve a problem. Such companies operate in a variety of industries from all over the world including Google, NASA, Coca-Cola, Toyota, and Unilever.

As the fast pace of technology calls for innovative, out-of-the-box thinking, corporations are looking for more unusual approaches to meet the challenges they face, often with “hands-on” or “unplugged” approaches. If LEGO is about anything, it’s the use of one’s hands while the mind is in an unplugged state. LEGO Serious Play capitalizes on this by asking the hands to find a solution that the mind hasn’t been able to on its own.

Play helps uncover things you didn’t know you knew

Think about one of your passwords. Quite often we can remember it faster if we are able to type it out. In fact, if the keypads change (ie typing numbers on a keyboard vs. phone dial layout), you might even move more slowly because the fingers have forgotten where to go. Rasmussen understands this phenomena and believes it is an integral strength of LEGO Serious Play.

“This is why I use the analogy: the hands function like a Google Search engine,” he said. “The subconscious rules us.”

LEGO Serious Play is all about bringing those valuable subconscious thoughts to the surface. LEGO is unlocking the knowledge from the people they feel are the most qualified to offer solutions: the employees themselves and not outside consultants. But can little bricks made for kids really do that?

“That’s certainly possible,” said organizational and industrial psychologist, Robert Litchfield, who is associate professor of Economics and Business at Washington & Jefferson College. He also told Quartz that using play in the workplace to bring about more creativity is not a new idea and hasn’t been researched thoroughly. Still, Litchfield explained that the act of using bricks in the boardroom may be setting up what he called an environment of psychological safety.

“You signal to them [employees] that creativity is wanted and you set up an environment for letting that loose.” Litchfield also said that once such an environment is set up, the chances of gaining more contributions from employees increase.

Rasmussen realized LSP had potential after he developed a prototype and tried it on his own team 17 years ago at LEGO Education. The moment of awakening came when the quietest members of his team shared some of the most valuable insights that day. He asked him why he had never contributed these ideas before and he replied, “Because I was never expected to.”

LSP is often welcomed because of the 80-20 principle applied to meetings: 20% percent of the group will talk 80% percent of the time, with the same people doing all the talking. Inevitably, one person will bring up an idea, another will concur with a slight modification, another is not listening as he is focused on what to say on his turn, and another participant will have just given up already and checked out. “These kind of dynamics are really what LEGO Serious Play was designed to destroy,” said Rasmussen.

Giving creativity a green light—a real one

Quartz spoke with a human resources manager at a globally established consulting and professionals services company, on the condition of anonymity, who used LEGO Serious Play to kick off the first days of training for an accelerated leadership program. The firm had created a new program to help a group of carefully selected managers further develop their skills. The trainees underwent approximately 100 hours of the program spread over eight months.

On the first day, in a workshop facilitated by Rasmussen, the trainees were asked: “How would you describe the difference between a manager and a leader?” In adherence to the LEGO Serious Play method, the participants were each given the same set of bricks and four minutes to answer the question by building it with LEGOs.

The anonymous HR manager said that it was essential to begin the training program with LEGO Serious Play. He really wanted to help create a different mindset and described what would have happened if they hadn’t used LEGO bricks: “You would get some sort of standard response such as ‘A manager is a doer and a leader has a vision,’” he said. “So we wanted to tap into the science of LEGO Serious Play and that is, if you are busy with your hands then you are busy with your mind.”

“Most people think that it can be difficult to get employees to express creativity at work because most of the incentives in organizations are against it,” Litchfield said. Company incentives usually encourage routine task performance. “We like to think about creativity as this awesome thing all the time, but that’s not really true. I mean, an organization that has all creativity all the time is going to be a total failure.” Litchfield explains that in general, creativity at work will be the minority activity and is likely to surface when people see something new is needed.

In the case of the managers that the HR manager had gathered for his program, the attendees contributed a variety of descriptions explaining the difference between a manager and a leader. What was most interesting was how their builds demonstrated their answers. One build was of a person watching a car go by. While it was simple, the revelation was profound. “It can be harder to recognize a moment that happens than a moment we create. It takes awareness to slow down and not pass an opportunity by.”

Another build depicted a person seated alone with a wall built between him and his colleagues. This contribution was entitled, “Stop having meetings with myself,” which basically meant the that attendee had been too concerned about whether or not his thoughts were ready for sharing.

For human resource managers like the one I spoke to, there is no question that LEGO Serious Play was effective. “People don’t come away from LEGO Serious Play unmoved.” The HR manager has even undergone training himself to become a certified facilitator and has held workshops without Rasmussen.

Toys without borders

Ioanna Tsitoura, chief human resources officer at WIND, a major telecommunications provider in Greece was charged with embedding new corporate values to the employees at her company, all 1,000 of them.

“We needed to raise awareness, understanding, engagement, and at the same time motivate our employees and strengthen the ‘one team’ feeling,” she told Quartz. To handle the large number and ensure that the workshops be carried out in Greek, Tsitoura hired a local agency to be trained to facilitate workshops with the large number of people.

Tsitoura chose LEGO Serious Play because it would allow for the group to sit, interact, and “play” with one another. Her goal was to have workers at varying levels, from call center agents to C-level employees, interacting with each other, to facilitate free thinking about the new company values, and “make them more than words on paper.” Tsitoura was able to take the input of employees, collect them, and create a manual that has become a key document at WIND.

“Although the message was by nature ‘soft,’ complicated and open to interpretation, we achieved a very good result investing only a couple of hours for each attendee,” she said.

Litchfield calls the toys in this scenario “boundary objects”: design made by any employee in his own viewpoint can still be viewed differently by the other participants.These boundary objects can reduce tensions and help each side understand the other side’s perspective. “By having this thing in front of them, they can talk across their functional differences.”

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that adults are looking for solutions through playing with LEGO bricks. It’s not just because of all of the theory behind building and communication introduced by experts. Rather, we can also credit some of our greatest influences: our own children. Their obsession with the bricks, the marvel of those mini-figures can’t help but spark curiosity in adult minds. It is no wonder that these magical modular bricks are being used to assist in sharing ideas and collaborating creatively in any type of setting, from playrooms all the way to boardrooms.