The enigma behind America’s freak, 20-year lobster boom

Drizzled in butter or slathered in mayo—or heaped atop 100% all-natural Angus beef, perhaps? The question of how you like your lobster roll is no longer the sole province of foodies, coastal New Englanders, and people who summer in Maine. American lobster has gone mainstream, launching food trucks from Georgia to Oregon, and debuting on menus at McDonald’s and Shake Shack.

Drizzled in butter or slathered in mayo—or heaped atop 100% all-natural Angus beef, perhaps? The question of how you like your lobster roll is no longer the sole province of foodies, coastal New Englanders, and people who summer in Maine. American lobster has gone mainstream, launching food trucks from Georgia to Oregon, and debuting on menus at McDonald’s and Shake Shack.

Unlike almost anything else that gets eaten on a bun, Maine lobster is wild-caught—which typically makes seafood pricier. So how has lobster gone from luxury eat to food-truck treat?

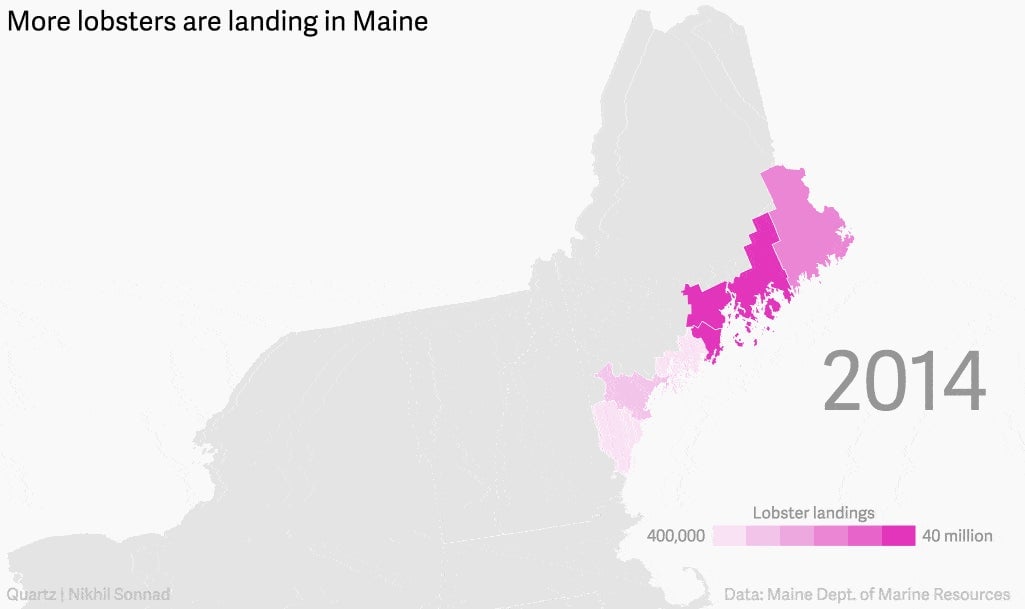

The reason boils down to plentiful supply, plain and simple. In fact, the state’s lobster business is the only fishery on the planet that has endured for more than a century and yet produces more volume and value than ever before. And not just slightly more. Last year, Maine fishermen hauled ashore 124 million pounds of lobsters, six times more than what they’d caught in 1984. The $456 million in value those landings totaled was nearly 20% higher than any other year in history, in real terms. These days, around 85% of American lobster caught in the US is landed in Maine—more than ever before.

Even more remarkable than sheer volume, though, is that this sudden sixfold surge has no clear explanation. A rise in sea temperatures, which has sped up lobster growth and opened up new coastal habitats for baby lobsters, is one likely reason. Another is that by plundering cod and other big fish in the Gulf of Maine, we’ve thinned out the predators that long kept lobster numbers in check. Both are strong hypotheses, yet no one’s sure we really understand what’s going on.

Even as biologists puzzle over Maine’s strange serendipity, a more ominous mystery is emerging. A scientist who tracks baby lobsters reports that in the last few years their numbers have abruptly plummeted, up and down Maine’s coast. With the number of breeding lobsters at an all-time high, it’s unclear why the baby lobster population would be cratering—let alone what it portends. It could reflect a benign shift in baby lobster habitats. Or it could be that the two-decade boom is already on its way to a bust. To form a clearer picture why, we first need to unravel the possible causes of the current lobster glut.

Maine lobstermen: early adopter conservationists

For a long time, the common wisdom was that more than 80% of Maine lobsters of legally harvestable size are killed each year, to be minced into bisque or slathered onto rolls. When you’re blotting out that many of them, how do you guarantee a steady supply of baby lobsters to keep the population growing?

Maine lobstermen approach this question differently from almost any other fishery—and have for more than half a century. Most fisheries forbid fishermen from bringing to shore fish under a certain size, and limit the accumulated weight of fish caught. The idea is to protect the juveniles so that they can propagate the species.

But the logic of this strategy defies biology—particularly in the sea, where many species tend to grow more fertile with age.

Lobsters are a case in point. When a female produces eggs, they cling by the thousands to her underside like clusters of tiny, dark-green berries. Egg production generally rises exponentially with a female lobster’s size (a decent proxy for age since we still don’t know how to tell how old lobsters are). An eight-inch female carries half as many eggs as a 10-incher, and one-quarter the number of eggs clinging to a foot-long female, and so on.

Rather than ignore the science, as many fisheries do, Maine scientists and lawmakers recognized early on that protecting big lobsters preserved the breeding stock. And not just big females. Since they prefer even heftier mates, big male lobsters needed protection too. Starting in 1933, lobstermen were required to throw back any ”jumbos,” lobsters larger than 4 and 3/4 inches, measured from eye socket to tail (these days it’s 5 inches). They also must release “shorts”—specimens smaller than 3 1/4 inches.

Then there’s the opt-in conservationism of “v-notching.” For half a century, Maine custom has obligated lobstermen not just to throw back any egg-bearing females they caught; but also first to cut out a “v” into her back tail-flipper. This mark, which her shell will bear for decades, signals to anyone who catches her in the future that she is fertile and must be thrown back. (The practice officially became law a little over a decade ago.)

The upshot of these policies is that Maine lobstermen only catch medium-sized lobsters that haven’t been caught bearing eggs. This leaves bigger lobsters and fecund females to replace the ones we eat.

Doomsday prophecies

But in the 1970s and ’80s, government scientists doubted the benefits of this elective environmentalism. Many warned that Maine’s lobster industry was on the brink of collapse.

“Over-exploitation certainly does exist now,” James Thomas, the state’s leading biologist, said in 1980, as Colin Woodard recounts in The Lobster Coast. “They’re fishing the lobster population way over the maximum that it can support.”

It’s not hard to see why he and others thought that. For four decades, Maine lobstermen had hauled in around 20 million pounds a year, on average. More and more fishermen were turning to lobstering as groundfish like cod and hake were depleted—which meant more traps in the water. In 1950, Maine lobstermen landed about 18 million pounds of lobster with around 430,000 traps. By 1975, the number of traps had more than quadrupled to 1.8 million. Yet lobstermen caught just 16 million pounds of lobster.

This pattern looked a lot like other fisheries on the eve of collapse: more boats, more men, more effort—and less to show for it.

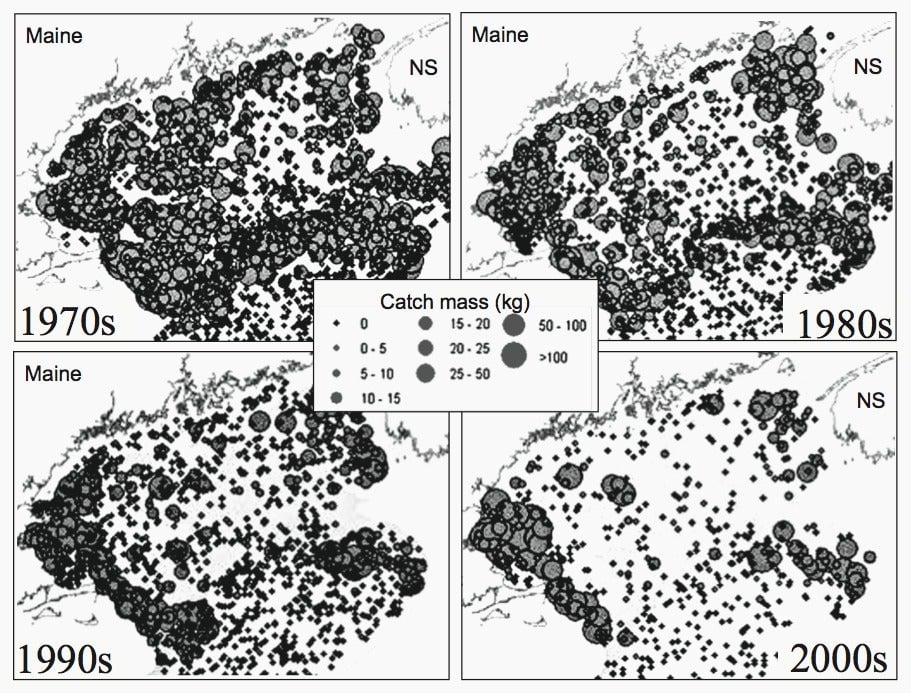

Then, out of nowhere, in the early 1990s, lobster landings surged. By the end of the decade, Maine’s lobstermen were hauling ashore 50 million pounds of the big-clawed crustaceans each year.

At the time, this was hailed as a triumph of Maine lobstermen’s ethics and foresight. As industrial trawling was decimating fishing stocks up and down the Atlantic seaboard, Maine’s lobster boom seemed proof of the self-sustaining virtues of communitarian, artisanal fishing.

It’s a story you want to believe. But lobstering policies are only a tiny sliver of the real ecological drama underway. By the late 2000s, it was clear that Maine’s lobster population exploded beyond any proportions that could be explained as dividends from sound conservation alone.

Will this bonanza continue? That would be easier to answer if we knew for sure what was causing it. The problem is, we don’t.

Behind Maine’s mysterious lobster bonanza

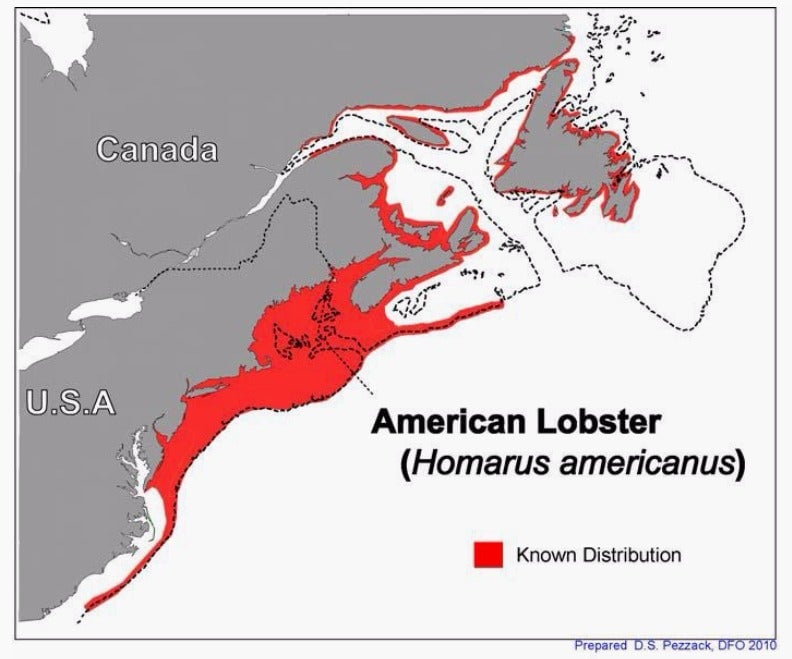

Some obvious factors may help explain what’s going on. The increase in traps is likely part of it, as is the improvement in lobstering technology. But a much bigger cause is probably that the Gulf of Maine—the shallow patch of sea between Cape Cod and the southern tip of Nova Scotia—has been heating up faster than 99.9% of the world’s oceans.

Cooled by the Labrador Current that swoops down from the Arctic, the Gulf of Maine is much chillier than the rest of the Atlantic coast. This is ideal for American lobsters, which generally prefer waters between about 41°F and 64.4°F (5-18°C). Historically, that’s kept the lobster population centered around Maine’s southern shores.

Before 2004, average temperatures in the Gulf of Maine had been notching up at a rate of about 1.8°F every four decades. Then they abruptly began rising at a much steeper rate—1.8°F every four years—according to a 2013 study (pdf) by a team of scholars mostly from the University of Maine.

The brisk clip of warming has pushed lobsters steadily north. Bob Steneck, ecology professor at University of Maine, has traced that lobstering “sweet spot” as it’s crept up the coast, first from Casco Bay, off Portland in southern Maine, in the 1980s to where it is today—in Stonington, about 100 miles to the northeast.

This lobster migration isn’t just about comfort. Whether and when they pass to the next stage of their lifecycle often depends on finding seas that are suitably temperate.

Helping lobsters bulk up

In lobster land, size is survival. Big lobsters can muscle their way into choice dens, deter predators, and—for males at least—attract mates. The crustacean grows much faster in relatively warmer seas. A southern New England lobster reaches harvestable size in about five years. In the frosty waters of Canada’s Bay of Fundy, on Maine’s eastern border, it can take from six to 10 years. In addition, females in more temperate waters become fertile younger. Southern New England females, for instance, reach sexual maturity when they’re around half an inch smaller than their Bay of Fundy cousins.

Their search for warmth spurs a semi-annual lobster migration. Icy winds that whip off the land in winter chill inshore shallows, sending lobsters scuttling down the coastal shelf to relatively warmer pockets. Then as the sun heats the sea in late spring, lobsters awaken from their torpor and trek back toward the shore to eat, mate, and bulk up.

Egg-bearing females are particularly hell-bent on escaping the cold. During the nine to 12 months the eggs layer a female’s underside, they require enough warmth to develop. And only when seas are sufficiently summery—typically in June in southern New England, and well into August the closer you get to Canada—will the babies hatch into shrimp-like larvae.

At the mercy of currents, wind, temperatures, and the appetites of passing fish, the vast majority of these hatchlings don’t make it. Those lucky few that do will, within a month or two, have grown into a tiny, fully-formed lobster about the size of a cricket. Now big enough to swim, these larvae dive to the seafloor to settle in rocky crannies, where they’ll hide out for the next few years, until they’re big enough to fend for themselves.

The price of your lobster roll ultimately depends on how many of these babies survive. It seems clear that many multiples more little lobsters are making it into adulthood—and eventually onto butter-sopped buns—than in the past. This probably has something to do with the fact that, like their parents, babies also benefit from milder Gulf of Maine temperatures.

Location, location, location

Even in deep summer, the waters of eastern Maine and Canada’s Bay of Fundy have traditionally been bracingly chilly. This is fine for adult lobsters. Their offspring have a tougher time, though. Lab experiments suggest that in seas below about 54°F—a common enough summer temperature in those areas—many babies struggle to survive at all. Even among the hardier specimens, few grow big enough fast enough to make that crucial descent to the seabed.

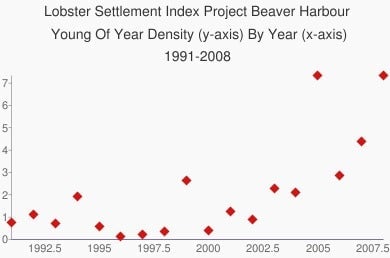

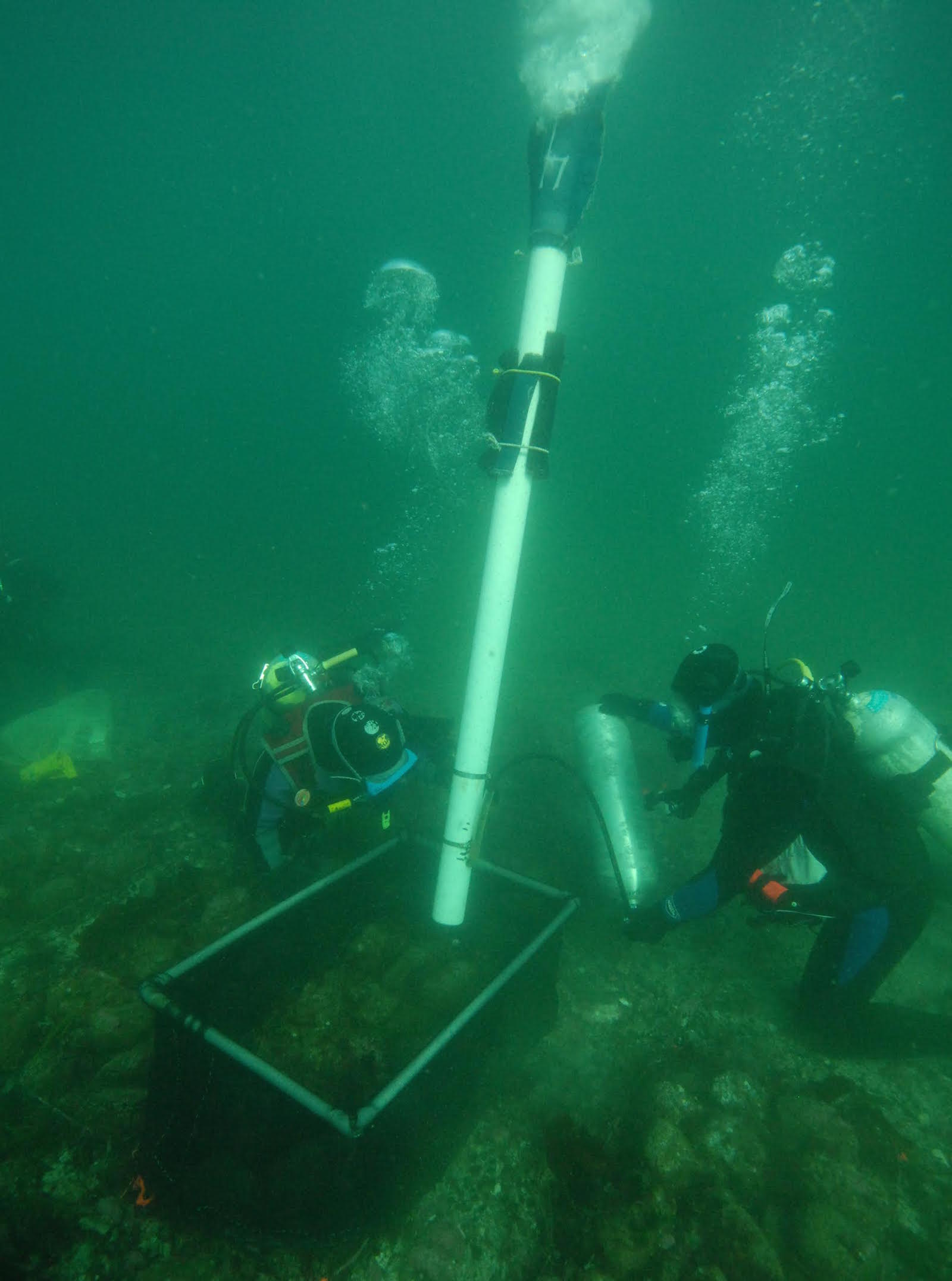

In the early 2000s, however, the Bay of Fundy stopped being such a baby lobster deathtrap. This discovery came from Rick Wahle, a biologist at the University of Maine who developed a sampling method used to count baby lobsters settled in the Bay of Fundy’s Beaver Harbor since 1989 (the data were generated by Canadian biologist Peter Lawton). For more than a decade, the team of divers found fewer than one baby per square meter, on average. Then babies started moving in. In 2005 and 2008, they found more than seven settled baby lobsters per square meter, on average.

A similar upswing was underway on the other side of the border, in eastern Maine, whose waters also have long been too cold for baby lobsters. It seems likely that the warming of these typically colder northeastern swaths of the Gulf of Maine was letting more babies make it to the sea bottom, where they found the gravelly detritus left by ice age glaciers.

This “cobble,” as scientists call it, makes the perfect nurseries for baby lobsters. And once settled, they were clearly thriving. A few years after Wahle started tracking the baby settlement uptick, lobster landings both in the Bay of Fundy and in counties Down East, as Mainers refer to the their state’s northeastern edge, soared.

Warming may only be half the answer

Intuitively, spiking sea temperatures seem a pretty solid explanation for much of the Maine lobster boom. More females giving birth at smaller sizes—before they can be legally caught—not only means more babies per each new generation. It also means more v-notched females. Finally, thanks to warmer seas and plum new habitats, more babies than before are surviving.

Statistics seem to bear that out: Even if you strip away the overall trend and focus on the discrete changes, the warming trend and the leap in lobster landings line up pretty clearly, says Andrew Pershing, chief scientist at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute (GMRI).

But the causal effect suggested in this relationship isn’t as obvious as it might seem.

“That [correlation] could be [a sign of] more lobsters over the 30 year period,” says Pershing, “But year to year, it’s also that in warm years we catch more lobsters—you basically have this period in the summer where it’s warmer and lobsters are active and you can catch them really quickly.”

In other words, we know that Maine lobstermen are catching a lot more than usual, and temperature is very likely part of the cause. But we don’t know whether there are actually more lobsters down there, or whether the warmer water is making them easier to catch.

And then there’s this point, which appears to undercut the thesis: The very beginnings of the great Maine lobster surge predates the Gulf of Maine’s big temperature rise by roughly a decade.

Man and cod

The second big hypothesis behind the sudden lobster abundance is simply that human seafood-lovers have rubbed out many of their predators—sharks, hakes, haddock, skates, rays, and above all, cod.

As voracious as they are massive—they can grow up to 2 meters (6.6 feet)—cod zip through the northeastern Atlantic with their mouths agape, gulping down worms, shrimps, herring and whatever else they can swallow. Including, of course, lobsters. Throughout much of the last millennium, European fleets trolled the Atlantic in search of cod. But it wasn’t until the 1930s, when refrigerators let fishermen catch cod with abandon, and throughout the next few decades, as fishermen souped up their trawlers with engines, that Maine’s cod population dwindled dangerously.

This would throw any ecosystem out of whack. But Maine’s is uniquely flimsy. One of the planet’s youngest oceans, the North Atlantic also claims an unusually low diversity of species. The sparse lattice of creatures in Maine’s food chain mean that even a small change in one species’ population can throw others out of whack. This makes for sudden booms, and just as sudden busts.

Cod sit at the very tip-top of this unusually fragile food chain—an “apex predator,” as they’re called, that keeps lobsters and other species in check. With cod and its fellow apex predators obliterated, the creatures that they once ate exploded in number. And because these smaller creatures tend to feed on cod eggs and larvae, they may be making it hard or even impossible for cod and other apex predators to bounce back.

There may be another factor at play, though. Heavy fishing not only shrank cod numbers; it also shrank their average body sizes. Research suggests the average cod size fell 20% between 1997 and 2007. A recent study (paywall) by Rick Wahle and colleagues linked the lobster boom more closely to the shrinking sizes of predator fish, than to the population decline itself.

Normally, roving predators restrict lobsters to tiptoeing around their rocky grottoes. With fewer—and much wimpier—predators to worry about, lobsters can wander unprotected seabed terrains with new abandon. Both Wahle and GRMI’s Pershing say this is consistent with what they hear from lobstermen: They’re catching lobsters in areas that, two decades ago, lobsters never went.

So the boom might not just be due to abundance. The fact that lobsters are no longer stuck cowering in their craggy dens may also be making them easier to catch.

Domesticating the American lobster

If shrinking cod tilted the ecosystem in favor of lobsters, fishermen then unwittingly gave the crustaceans another boost—what UMaine’s Bob Steneck calls “the domestication of the Gulf of Maine.”

“We did it on land literally thousands of years ago,” he says. ”Removing the predators and adding food is generally good animal husbandry.”

In the case of Maine’s lobsters, that second part of the domestication equation—adding food—hinges on herring. With cod and other herring predators winnowed down in size and number, the cheaper, smaller fish were becoming more plentiful. Americans don’t much care for herring. But lobsters sure like it.

These days, herring is the prime bait used in lobster traps, the few-foot-tall metal crates. Here’s a demonstration of how one works:

Despite their names, they don’t actually “trap” at all. Using undersea cameras to spy on a trap, scientists discovered that only 6% of lobsters that wandered into a trap stuck around long enough to get hauled to the surface. Why do so many lobsters mosey through and then leave? For the all-you-can-nibble herring, naturally.

There are close to four million traps in Maine waters, says Steneck—each one packed with about a pound of bait per day. ”Most of the lobsters that go into traps are undersized and can’t be harvested,” he says. “They get a free meal.”

All those free meals boost the population—and the industry. GMRI researchers calculated that during trapping season, herring accounts for between a third and half of lobsters’ diets. Those in areas with traps grow 16% faster than lobsters in areas without, according to their research. This extra heft also adds around $40 million a year to the value of Maine’s lobster haul.

The success of this domestication process perpetuates itself. As other fisheries founder, both Maine’s fishermen and the state’s economy have grown increasingly reliant on its swollen lobster haul. The lobster fishery’s total economic impact on the state economy was $1.7 billion, as of 2012—more than 3% of Maine’s GDP that year.

However, twilight may already falling on Maine’s two-decade crustacean heyday. Though the contents of this season’s lobster traps signal nothing but bounty, scientists are uncovering grim omens from under the rocks below.

Bad news from the baby lobster census

The first comes from Rick Wahle’s annual survey of baby lobster settlement. Using scuba divers and, in deeper water, retrievable boxes that simulate cobble, he and his team have counted baby lobsters at more than 100 sites in Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Canada, a few for more than 25 years. As you’d expect, their findings suggest that wherever baby lobsters settle in big numbers, adults soon abound.

What about the obverse, though? We’re about to find out.

In the last few years, Wahle and his team have tracked what he calls a “widespread and deep downturn” in the number of settled baby lobsters. Though there have been decreases at certain sites before, the signals they’re picking up now are different.

“We’ve seen other downturns—they blink on and blink off. But we’ve never seen all of them blink on like that.”

The slump in babies started around 2011, which means “the next two years are going to be very telling because of that downturn in settlement,” says Wahle.

The case of the missing lobsters

What’s strange is that, by all reckoning, Maine’s lobster population should be at an all-time high—which means baby lobsters ought to be too. There are also more breeders than ever before. The state’s lobsters are better fed, better protected, and—in the upper Gulf of Maine, at least—they and their babies enjoy more favorable sea temperatures than at any time in history.

“That we see such a dramatic decline in settlement here at a time when brood stock, the spawners, are at peak levels of abundance—there must be an environmental factor here,” says Wahle.

There are a couple of things that this could mean. One is what Steneck—he works closely with Wahle, a former student of his—calls the “deep water hypothesis.”

In the past, most larvae likely settled in the upper 60 feet or so of the coastal shelf, where waters were sufficiently warm. However, cobblestone and rocky ledges extend a ways offshore in places, perhaps 100 feet down. So as the water has gotten balmier, they’ve been able to make their homes farther offshore—in waters that used to be too cold for them—well beyond where Wahle and his team are looking for them. The kids, in other words, are alright.

In another scenario, they’re not, though. Steneck says that deeper water—where lobsters spend winter—seems to be warming faster even than shallow areas. If this means a females’ eggs mature and hatch while she is still far offshore, her babies could be carried out to sea by currents into waters too cold and deep for babies to survive.

“The first scenario, if true, would be very positive, the second one very negative—it would mean we’re going to see a significant downturn [in landings],” says Steneck. “I just don’t think we have a clue which one of those is correct.”

On the bright side, the first scenario jibes with reports from fishermen who’ve been hauling up baby lobsters and juvenile lobsters in unusually deep waters, suggesting that babies are successfully settling there. But new research on female lobster fecundity could tip the scale in favor of the much grimmer outlook.

Trouble with Grand Manan’s big mamas

The findings raise the possibility of another culprit entirely: Female lobsters are suddenly producing fewer eggs. This seems unlikely given the prime baby-making conditions created by the warming seas. However, recent research (paywall) led by Heather Koopman, a biologist at the University of North Carolina, suggests this might be happening—and ocean warming is probably why.

To analyze lobster fecundity, Koopman and her team tagged along with lobstermen working the waters near Grand Manan Island, in Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy. Home to some of the biggest female lobsters ever recorded, the island is also a spawning hotspot for the whole region, an important source of current-carried larval emigres far down Maine’s coast. Before tossing back each “egger” that the lobstermen hauled up, Koopman and her team counted her eggs (or took digital pictures so they could tally them later). Over five years, they sampled some 1,370 lobsters, building one of the biggest collections of data on lobster reproduction ever amassed.

The results were disconcerting. From 2008 to 2013, the average number of eggs they counted on a lobster’s underside declined by 30%—a drop of around 8-10% a year.

Canadian bakin’?

What might explain this alarming drop in fecundity? Stress from handling, pollution, disease, and lack of oxygen could in theory be factors.

However, the most likely cause, hypothesized Koopman and her team, is the rapid rise in water temperatures. While some warming is obviously favorable to lobster populations, too much is dangerous. A female lobster’s ovaries mature when temperatures drop somewhere below the 41°F to 46.4°F range. During the five years of the study, water temperatures never fell below 41°F, and only a few times below 46.4°F. If Koopman and her teams’ hypothesis is right, it also doesn’t bode well for egg production further south, in waters already much warmer in winter than the Bay of Fundy.

Another possible factor behind the Grand Manan Island fecundity decline could be that there simply aren’t enough big male lobsters left to go around. Female lobsters generally prefer mating with bigger males. That’s not as easy as it used to be though, explains Tracy Pugh, a Massachusetts state fisheries biologist who specializes in lobster reproduction. The more rigorous protection of eggers (Maine’s conservation policies are the norm in Canada too) makes it highly likely that many more females than males will avoid harvest long enough to reach the 5-inch legal limit.

So what happens when females outnumber males, or exceed them in size? In labs, at least, mating doesn’t always work out so well. Guy lobsters that try to get it on with bigger females sometimes simply fail to get the job done. Others release too little sperm to fertilize all of the large female’s eggs. And when females outnumber their counterparts, males sometimes can’t keep up with the demand. However, Pugh emphasizes that lab results don’t always reflect what happens in the wild.

Still, whatever is behind it, the fecundity decline of Grand Manan’s big mamas could indeed explain why fewer babies are making it to Maine cobbles than before.

The coming collapse?

These disquieting data might just be statistical noise—or they may foretell a reversal in the Gulf of Maine’s two-decade lobster boom. If any fishermen can weather such a downturn, it’s Maine’s lobstermen. Tempered by tradition, discipline, and the collective will of generations, their practices exemplify the long game of biological and economic sustainability that far too many other fisheries decline to play.

As the Maine’s lobster industry’s improbable rise reveals, no single species exists in a vacuum. Unfortunately, conservation efforts don’t either. Two decades of lobster abundance isn’t thanks to human mastery of ”sustainability.” The ecosystem extremes that seem likely to have produced it—how we’ve pulled apart the food web, heated up the sea, re-rigged the lobster population structure—are volatile. Inevitably, nature warps again.

If recent research is truly flashing a warning sign, that warping may already be underway. For most, that means that the local lobster roll food truck might switch back to selling kimchi tacos. But for a state whose identity is married to the iconic big-clawed crustacean, the stakes are much higher.

“We’re not talking about lobstermen having a bad decade,” says UMaine’s Steneck. “We’re talking about the entire maritime and coastal heritage of the coast of Maine.”

Lobster roll image by Yuri Long on Flickr, licensed under CC-BY-2.0 (image has been cropped). Juvenile lobster image by Rick Wahle via NOAA Photo Gallery on Flickr, licensed under CC-BY-2.0 (image has been cropped). Image of Maine cod fisherman by rich701 on Flickr, licensed under CC-BY-2.0 (image has been cropped).