Why Obama’s pick for Secretary of the Interior is a shrewd move

On the face of it, US President Barack Obama’s nomination on Feb. 6 of Sally Jewell to head up the Department of the Interior, which manages the country’s massive portfolio of public land use, is an unconventional one.

On the face of it, US President Barack Obama’s nomination on Feb. 6 of Sally Jewell to head up the Department of the Interior, which manages the country’s massive portfolio of public land use, is an unconventional one.

Jewell has worked exclusively in the private sector—she’s currently the CEO of REI, which sells sporting and outdoor goods—whereas interior secretaries are almost always politicians, like the outgoing incumbent, Ken Salazar. Jewell’s CV includes extensive experience in the oil and banking industries, suggesting a “pro-business” background that Republicans typically prize more than Democrats.

But Obama needs someone who can “get” business enough to make smart calls on hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”), but also share his policy priorities on conservation and renewable energy.

The role is a big deal because the secretary ”has wide discretion to manage extraction and protect public lands—it’s an ongoing, built-in tension of responsibilities,” David Alberswerth, senior policy advisor of The Wilderness Society, an advocacy group, tells Quartz. If confirmed, Jewell will also oversee a sweep of land that constitutes nearly one-quarter of the entire US—and generates $11.9 billion each year, mostly from leasing royalties to natural-resource extraction companies. Among government cabinets, only the Department of the Treasury brings in more revenue, says Alberswerth.

The tension between those duties is as taut as ever. Oil and gas industries argue that there are too many restrictions on access to public lands at the same time as Obama continues his push to develop renewable energies. Jewell will have to manage that tussle. Dicier still will be the establishment of new federal rules for fracking, the hydrocarbon drilling technique which environmental protection groups say pollutes water and air.

The trump card extractive businesses play has always been the jobs and revenue they generate for local economies—a good many of which are rural and therefore have few alternatives. Environmentalists have struggled to argue against that, because the value of ecological preservation is impossible to quantify.

Enter the so-called “outdoor recreation industry”—a unified front of companies in tourism, manufacturing and retail, among others. Last year, the industry generated $646 billion, creating jobs for 6.1 million people (pdf, p. 2), according to the Outdoor Industry Association (OIA). Its interests tend align more with those of nature-lovers, but it can make its case in the same terms—jobs and economic benefit—as the energy firms.

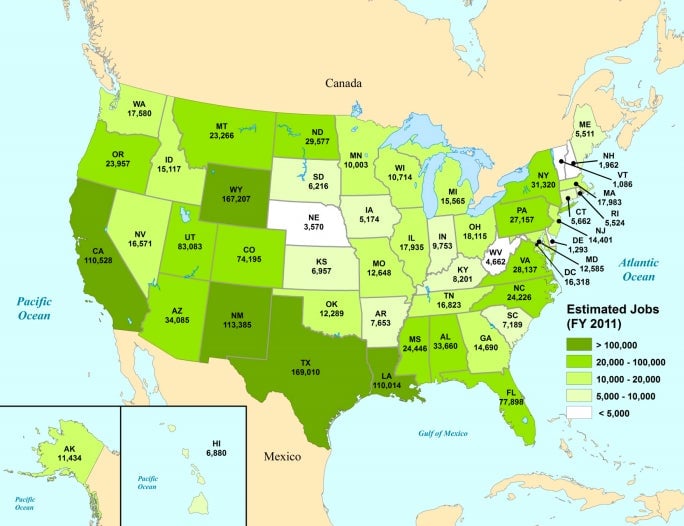

Still, it has a ways to go in its bid for increased influence. Though the Department of the Interior currently recognizes the industry in its economic impact assessments, its 2011 report found that oil, gas and coal made up two-thirds of jobs created, compared with just 19% from “recreation and tourism” (pdf, p. 151).

But the industry offers an alternative source of jobs and growth—one that Obama happens to be a fan of. And the president seemed to be emphasizing that argument when, in his introduction of Jewell, he praised her for knowing “the link between conservation and good jobs.”

Jewell surely does. REI, whose camping, rock-climbing, distance-running customers tend to be fiercely environmentalist in outlook, has been closely involved in promoting the outdoor recreation industry in general as well as the OIA itself.

“When you think about this appointment, it’s the first time you have someone—a CEO—from our industry coming into the Department of the Interior,” Frank Hugelmeyer, OIA’s CEO, tells Quartz. “I actually find this curious, that this is a big surprise. When you look at Treasury secretaries, they’re often from the investment world. So we see this as completely appropriate and overdue.”