Thousands of people have gone missing in Mexico, and the world is finally noticing

This post has been updated.

This post has been updated.

Since the abduction of 43 students in the Mexican state of Guerrero last year, a procession of international observers has been scrutinizing the state of human rights in Mexico. They don’t like what they’ve found.

After a recent, five-day fact-finding trip to the country, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) called the situation on the ground a “serious human rights crisis.“ That followed reports in February and March (links in Spanish) by United Nations officials concluding that disappearances and torture have become a widespread problem there.

The latest watchdog to touch down in Mexico is the UN’s high commissioner for human rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, who over three days starting Oct. 5 met with a variety of Mexican officials, including president Enrique Peña Nieto, as well as human rights groups and victims’ relatives. On the last day of his visit (Oct. 7) he said the case of the missing 43 students is a microcosm of the situation in Mexico, and called the government’s failure to clear up thousands of disappearances deplorable and tragic.

“Ignoring what is happening in this great country is not an option for us,” he said during a press conference.

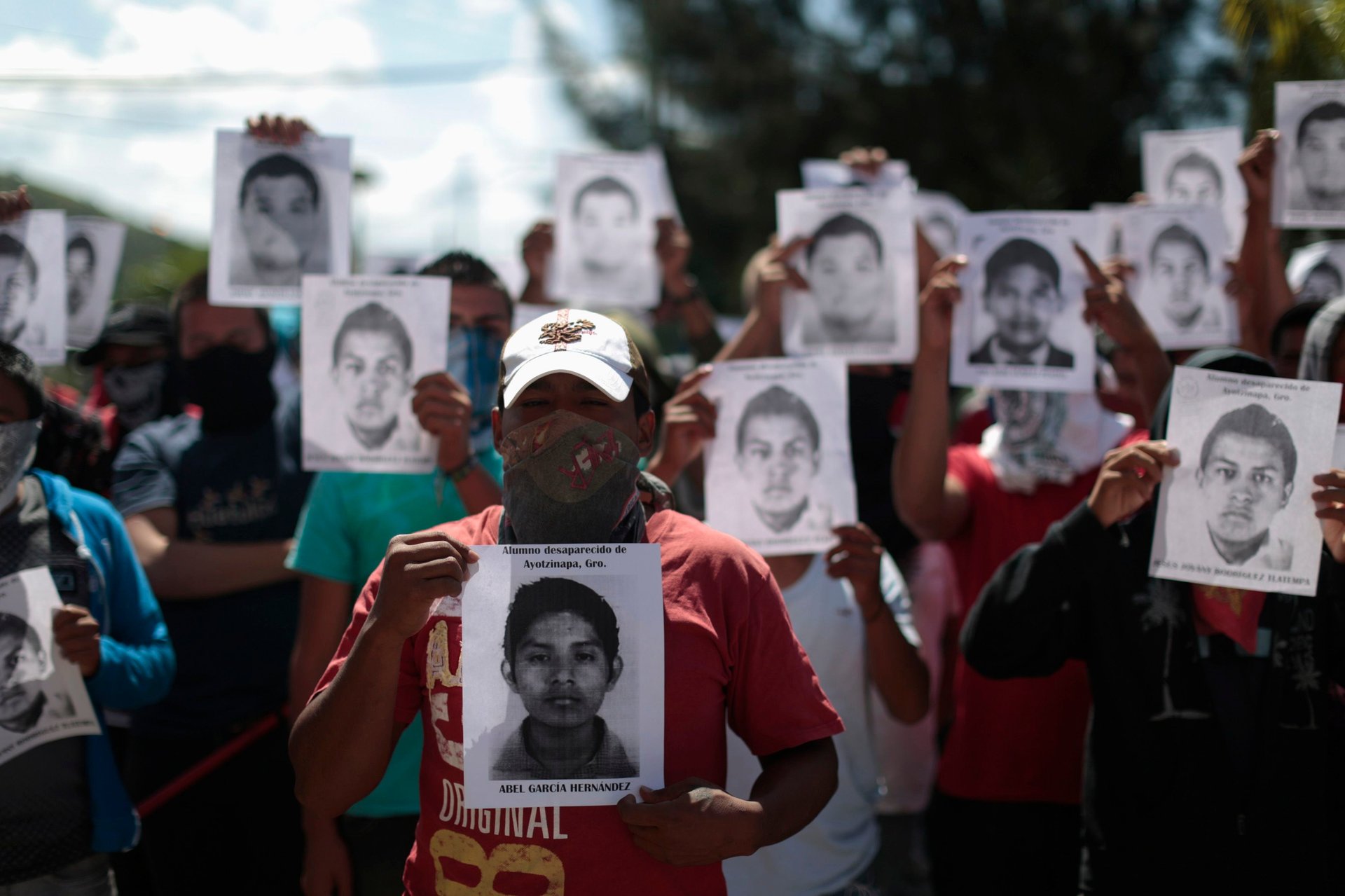

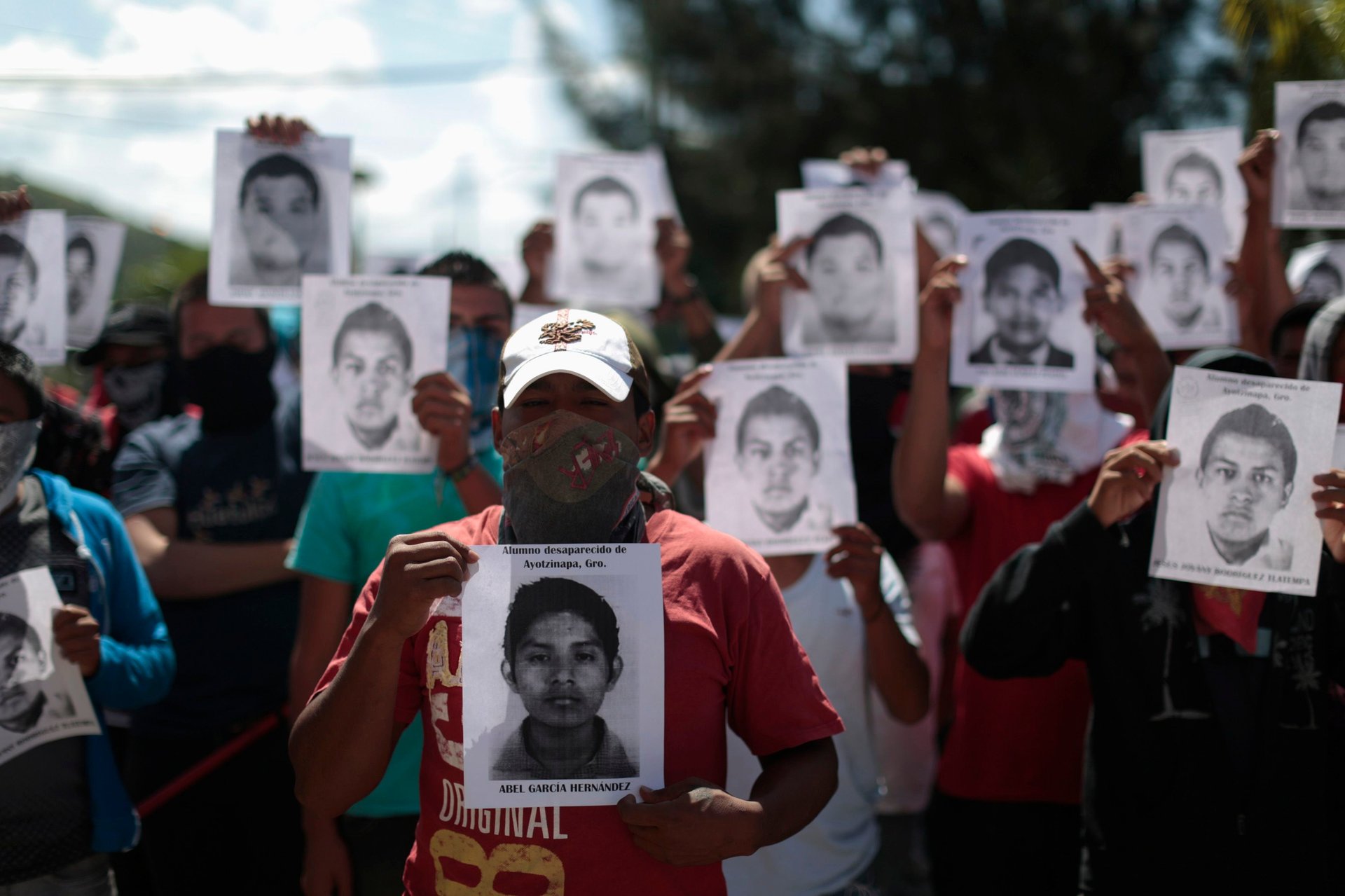

Ayotzinapa’s 43, named after the small town where they attended a rural teachers college, are bringing unprecedented national and international attention to Mexico’s much broader problem with unexplained disappearances.

Because of that case, more than 100 bodies have been unearthed by relatives of the missing students in the outskirts of Iguala, the city where they were taken, according to a preliminary report from the Inter-American commission. The search for the missing 43 also is exposing the plight of some 26,000 other people (link in Spanish) who make up Mexico’s disappeared.

In their assessments of Mexico’s record, UN officials and IACHR commended the government for reforming laws and creating new ones to ensure human rights are respected. But their overall conclusions were that impunity is rampant and the violence extreme.

Mexican officials are bristling at the criticism, downplaying some of the international agencies’ findings and flat-out disagreeing with others. Mexico’s defense secretary is reportedly refusing to cooperate with IACHR-appointed experts investigating the events in Iguala, saying there are no links between his soldiers and the students’ disappearance.

But some human rights groups say the international attention on Mexico is already making a difference. IACHR’s expert committee, for example, has for the first time provided Mexicans with “direct access to impartial and reliable information about an investigation as it happens,” Stephanie Brewer, a lawyer who works for Centro Prodh, a Mexico City-based human rights nonprofit, tells Quartz.

And the IACHR committee’s report on the case, issued last month, challenged the government’s probe, prodding federal investigators to dig deeper.

(Updated at 7:17pm EST on Oct. 7 to include comments from a press conference held earlier in the day.)