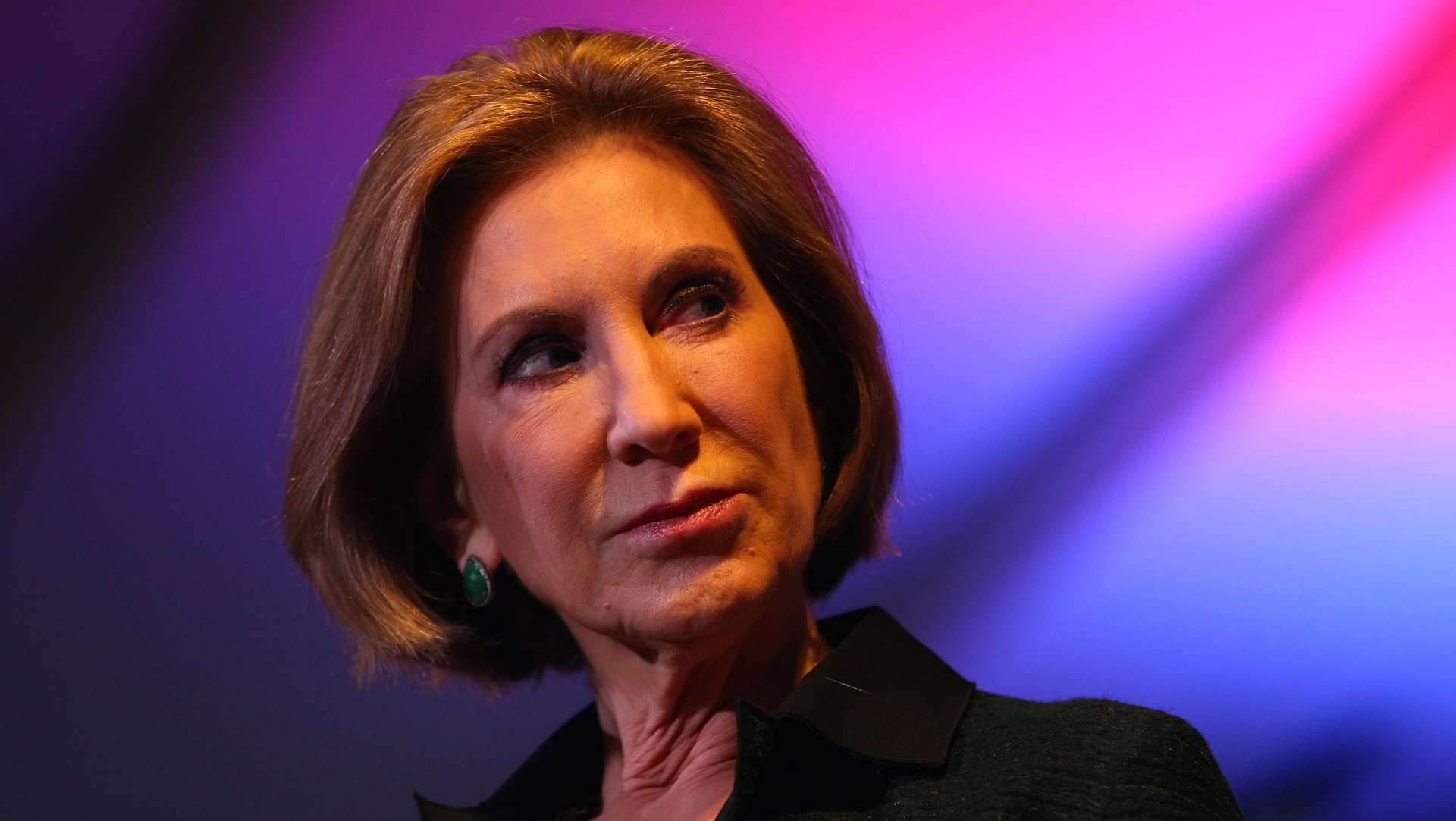

Carly Fiorina was a way better business leader than history will remember

Since Carly Fiorina entered the world of politics, pundits have used her business record against her. Today critics accuse the Republican presidential candidate of making bad decisions during her tenure as head of Hewlett-Packard and steering AT&T spinoff Lucent Technologies into a period of poor performance.

Since Carly Fiorina entered the world of politics, pundits have used her business record against her. Today critics accuse the Republican presidential candidate of making bad decisions during her tenure as head of Hewlett-Packard and steering AT&T spinoff Lucent Technologies into a period of poor performance.

But these jabs fail to put Fiorina’s record in context. When we judge businesspeople as political candidates, we should consider the economic climates they faced and the challenges specific to their industries. This is the best way to gather the information voters really need about a candidate’s instincts and ability to make good judgment calls in tough situations.

Pundits frequently ding Fiorina, who was a paid speaker at my company’s conference a decade ago, for Lucent’s questionable lending practices. While she was a senior executive at the company, Lucent made loans to customers with poor credit so they could afford the company’s equipment. Lucent’s low credit standards contributed to its near-collapse after Fiorina left for HP in 1999.

But such loans were standard across the industry at the time. If Fiorina had shied away from them, today’s critics would instead complain about Lucent’s subpar stock performance under her watch. And despite Lucent’s troubles, it wound up in better shape than its primary competitor, the now-bankrupt Nortel.

Critics also blame Fiorina for HP’s rocky financial performance during her tenure as CEO from 1999 to 2005. But this period coincided with the bursting of the tech bubble.

Fiorina’s detractors argue that PC manufacturers IBM and Dell fared better than HP during her reign. But they fail to mention that while HP relied heavily on companies to purchase its computers, its competitors had other lucrative business lines that helped offset reduced corporate demand. Dell was primarily a consumer brand at the time. And in addition to selling computers, IBM makes money from services like technical support and consulting.

Fiorina tried to catch up with IBM by purchasing PricewaterhouseCoopers’ consulting arm. But the deal fell through when HP investors balked at the high cost of the acquisition. Instead, Fiorina opted to buy Compaq—a decision that led to an ugly public battle with board members and her eventual ouster.

But just because Fiorina was fired does not mean that she failed. HP’s board was subsequently rocked by a spying scandal that clearly brings its decision-making ability into question. So does the fact that the board dumped its next two CEOs in short order. A board that sheds leaders faster than celebrities replace their spouses may well have been at fault in the dispute with Fiorina.

Moreover, some of the company’s partners now celebrate the Compaq merger they once protested. “In retrospect, yes, it was a good move for HP and for the partner community,” Don Richie, who initially opposed the merger as CEO of Sequel Data Systems, said in 2011. “I was wrong, and I’m glad they proved me wrong.”

It’s easy to cast any businessperson’s decisions in a bad light by focusing on selective details. A more nuanced evaluation of Fiorina’s career shows that she consistently had good instincts and made solid decisions, earning her frequent promotions.

The collapse of the tech industry hindered the success of many CEOs in the first decade of this century. A better way to evaluate Fiorina’s success might be to consider the arc of her multi-decade career.

During a period when promoting women was uncommon, Fiorina scaled the corporate ladder at every turn. She started as as a sales representative at AT&T in 1980 and quickly became a manager. She rose to the top of one major company and assumed a position of great power at another.

Companies promote people who are able to deliver results. It’s up to voters to decide whether the leadership skills necessary to run a huge enterprise correspond with those needed at the top position in government.