The US meat industry’s wildly successful, 40-year crusade to keep its hold on the American diet

This post has been updated and clarified.

This post has been updated and clarified.

Your doctor might tell you to eat fewer burgers and steak sandwiches, but thanks to the exceptional lobbying skills of the American meat industry, the US government probably never will.

Rejecting the advice of their own expert panel, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) announced this month that the latest edition of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans will not include considerations of environmental sustainability. Had they decided otherwise, they likely would have recommended that people lower their intake of meat, the production of which is widely recognized as a major contributor to climate change.

Health advocates are still hoping that the final guidelines, to be unveiled later this year, will include a directive to eat less red and processed meats, based on nutrition and health concerns alone. But if history is any indication, that hope is likely to go unfulfilled.

The meat industry has influenced the dietary guidelines for decades

The size of the US meat industry is immense. Beef alone is a $95 billion-a-year business, according to the USDA. And the North American Meat Institute (NAMI) estimates that, in total, the meat industry contributes about $894 billion to the US economy.

That size translates into political influence: In 2014, the industry spent approximately $10.8 million in contributions to political campaigns, and another $6.9 million directly on lobbying the federal government (calculated by combining totals for the meat processing and products and livestock sectors, as reported by the Center for Responsive Politics’ OpenSecrets website).

While the USDA is tasked with regulating the meat industry, it also has a role in promoting it. This tension plays out every time the US government wants to give out dietary advice—and the results generally wind up favoring the industry.

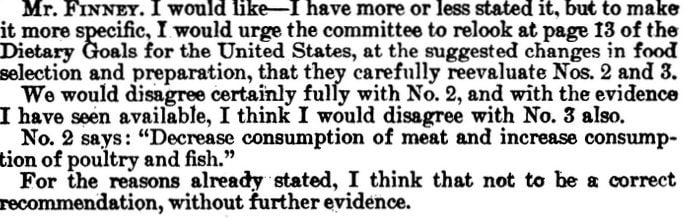

The pattern traces back to at least 1977, when Congress—a no less conflicted institution when it comes to coziness with the meat industry—had a more prominent role in setting nutrition guidelines. That year, a Senate committee report recommended that Americans decrease consumption of meat, eggs and other foods high in fat. This did not sit well with producers in those industries, who made their displeasure known at a hearing on the guidelines. As shown in the below exchange between the representative from the American National Cattlemen’s Association and senator Bob Dole of Kansas, the organization objected to a recommendation to decrease consumption of any of its products, even if paired with a recommendation to increase consumption of other ones.

In December of that year, the committee released the second edition of its report. A proposal to “[d]ecrease consumption of meat and increase consumption of poultry and fish” had been replaced with a recommendation to “[d]ecrease consumption of animal fat, and choose meats, poultry, and fish which will reduce saturated fat intake.” Senator George McGovern, who chaired the committee, was quoted as saying that he ”did not want to disrupt the economic situation of the meat industry and engage in a battle with that industry that we could not win.”

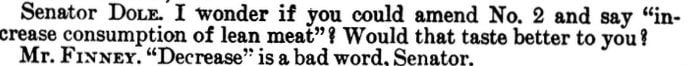

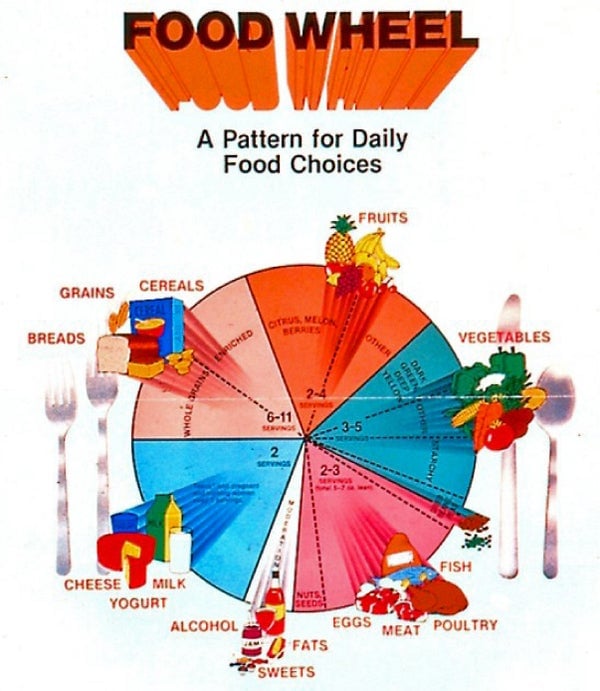

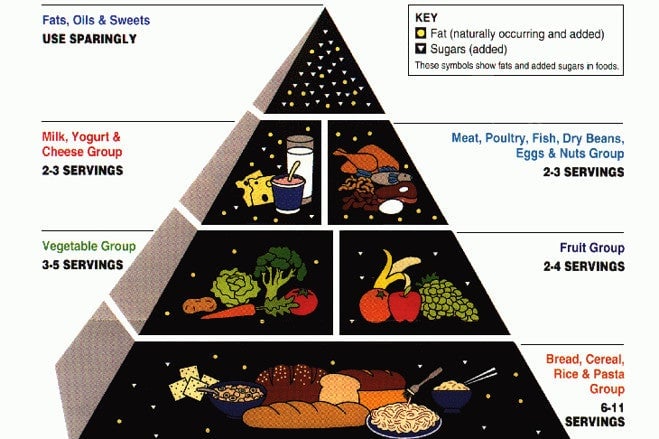

A similar battle played out in the early 1990s when the USDA replaced its food wheel, which visually put eggs, meat, poultry, and dairy on the same footing as vegetables, with a food pyramid, which made it clearer that Americans should eat more fruits and vegetables than meat, poultry, and eggs. In April 1991, the Washington Post published a story about the arrival of the Eating Right Food Pyramid. “There is no question that the basic food groups as they used to be presented really gave the impression that the most important things were meats and dairy products,” Joan Gussow, a nutritionist with the Columbia University Teachers College, told the paper. “This is a real mark of progress.”

By the end of the month, though, the new pyramid had been pulled. “Yielding to pressure from the meat and dairy industries, the Agriculture Department has abandoned its plans to turn the symbol of good nutrition from the ‘food wheel’ showing the ‘Basic Food Groups’ to an ‘Eating Right’ pyramid that sought to deemphasize the place of meat and dairy products in a healthful diet,” the Washington Post reported. As Alisa Harrison, director of information for the National Cattlemen’s Association told the Post, her organization worried that consumers would think the pyramid meant they should ”drastically cut down on their meat consumption.”

A year later, after an additional $855,000 in USDA spending, another pyramid was released with 33 small changes, including numbers that showed how many servings from each food should be eaten. (In the previous iteration, how much to consume was shown comparatively to other food groups and in less obvious text.)

As described in detail in this 1993 article by Marion Nestle of the New York University Department of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health, instead of saying to “eat less,” the guidelines came to include only positive instructions. In the most recent dietary guidelines, published in 2010, “lean meat” is listed in Chapter 4: Food and Nutrients to Increase.

This year, however, the advisory report preceding the updated guidelines explicitly advises to eat less red and processed meat, though the total amount of recommended meat intake is the same as it was in 2010.

The meat industry is not sitting idly by to see how the final guidelines turn out.

One tactic: Deny what the data show

While the 2015 advisory report included a footnote that ”lean meats can be part of a healthy dietary pattern,” the panel’s advice to eat less of specifically red and processed meat has run into the same industry objections that McGovern’s committee did in 1977.

“Lean meat is a headline, not a footnote,” said Barry Carpenter, NAMI’s president and CEO, in a statement the trade group released in February after the panel’s recommendations were released.

In response to an email inquiry from Quartz, NAMI extolled the healthfulness of meat as a reason to keep eating it at current levels. Americans “currently eat the recommended amount of protein, there is no reason for the government to reduce its recommended levels of meat and poultry,” NAMI spokeswoman Janet Riley wrote.

But as government data consistently shows, most Americans actually eat much more than their recommended daily protein intake (46 grams for women, and 56 grams for men). And among populations where more protein is necessary, lean meats, poultry, seafood, and plant-based proteins are the ones usually suggested by health professionals.

Another tactic: Attack the science

The efforts to keep Americans from lowering their meat intake include some important new allies. Nina Teicholz, author of The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat and Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet, and the Nutrition Coalition, backed by John and Laura Arnold, billionaires from Texas whose fortunes are tied back to Enron, have joined in as major power players in the fight, according to an in-depth report from Politico.

Their key tactic: Attack the scientific methodology used by those recommending a drop in consumption.

According to Politico, before the Nutrition Coalition was officially formed, Teicholz attended a meeting with representatives for ConAgra, the Grocery Manufacturers Association, and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, among others, to talk about whether criticizing the guidelines from the scientific standpoint would “create new opportunities” for rewriting the recommendations. Since then, Politico reports, Teicholz also has met with USDA staff, House Agriculture Appropriations chairman Robert Aderholt (R-Ala.), and Debra Eschmeyer, a senior nutrition policy adviser to Michelle Obama and the executive director of the first lady’s health initiative, Lets Move!. Teicholz, who describes herself as an investigative journalist, tells Quartz she has not taken money from the food industry for these activities.

Following her op-eds in the New York Times and Wall Street Journal about why Americans need more meat, dairy, and eggs in their diets, Teicholz also recently published a feature report in BMJ, formerly known as the British Medical Journal, directly questioning the scientific approach behind this year’s USDA/HHS advisory report. (She also argued that sustainability was irrelevant to the guidelines.) The BMJ story was underwritten by the Arnolds, who Politico reports “are spending an initial $200,000 to communicate [the scientific] critique” of the guidelines submitted by the government’s advisory panel.

The article has been widely criticized by nutrition experts for its many inaccuracies, both large and small. (BMJ told Quartz that the article was fact-checked “in line with our usual procedures” but did not respond to inquiries as to whether any corrections would be forthcoming.)

It is far from the only instance of the government’s expert panel being attacked for its methods. Republican lawmaker Mike Conaway of Texas, who chairs the House Committee on Agriculture and hails from the largest cattle-producing state in the country, wrote an op-ed for U.S. News & World Report echoing Teicholz’s article for BMJ by questioning the science behind the advisory group’s conclusions, as well as its decision to include sustainability as a factor in its recommendations. And as James Hamblin wrote in The Atlantic, at the recent Congressional hearing on the guidelines, lawmakers spent a significant amount of time questioning the scientific validity of the advisory report.

In a statement to Quartz, HHS and the USDA said the agencies “required the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee to conduct a rigorous, systematic and transparent review of the current body of nutrition science” and are “considering the Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, along with comments from the public and input from federal agencies, as we develop the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans to be released later this year.”

There’s no certainty about what the final guidelines will say in regards to meat consumption, but if the past is any guide, burgers, pork loins, and steaks will be far from the recommended dietary chopping block.

Updated Oct. 24, 9:30pm: This post was updated with a response from Nina Teicholz.