Iceland broke the Japanese whale-meat monopoly, but Japan seems not to care

Japan is one of the only countries in the world allowed by international regulation to hunt whales for meat—known euphemistically as “by-product“—under the guise of scientific research. However, in the last few years, the Japanese whaling monopoly has been hobbled by an unexpected threat: Iceland.

Japan is one of the only countries in the world allowed by international regulation to hunt whales for meat—known euphemistically as “by-product“—under the guise of scientific research. However, in the last few years, the Japanese whaling monopoly has been hobbled by an unexpected threat: Iceland.

The Arctic country’s surprise entry into the whaling business began in 2006, after some fancy legal footwork that allowed it to join Japan and Norway as the only countries permitted to hunt whales in any kind of volume. It’s not clear exactly what prompted this decision. Icelanders’ appetite for whale meat is minimal. But Iceland is a fishing powerhouse—former US Ambassador Charles E. Cobb once called it “the Saudi Arabia of fishing“—giving it the capacity to kill whales for meat if it wanted to.

And at least one Icelandic fisherman really wanted to get into the market. Multi-millionaire fishing tycoon Kristján Loftsson more or less, er, spearheaded Iceland’s whale industry. He’s sort of the Icelandic Ahab—impassioned about hunting whales. (Once when asked for his thoughts on research showing how intelligent whales are, Loftsson responded: “If they are so intelligent, why don’t they stay outside of Iceland’s territorial waters?”) His firm, Hvalur, which owns a controlling interest in one of Iceland’s biggest fishing companies, HB Grandi (pdf, p.5), is the only Icelandic company to hunt whales for meat. So by 2010, Hvalur had entered the Japanese market, according to whale industry researcher Junko Sakuma, ending the monopoly that Japan’s (grimly named) Institute of Cetacean Research (ICR) enjoyed via its sales arm, Kyodo Senpaku.

That monopoly has meant that the Japanese whale meat industry hasn’t had to be profitable for a while. Propped up largely by government subsidies, captive demand from public school lunches and the appetites of a dwindling number of elderly enthusiasts, the Japanese commercial whaling monopoly had few incentives to make a bona fide business out of hunting whales.

So Iceland’s entry into the market, says Patrick Ramage, the whale program director for the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), didn’t go over so well. ”The Japanese have no interest in the importation of relatively cheaper whale meat. There was [initially] a lot of meat being held up in customs,” Ramage told Quartz.”They were reluctant importers of the meat but Japanese importers with whom I’ve discussed this say there’s no legal reason to deny importation.”

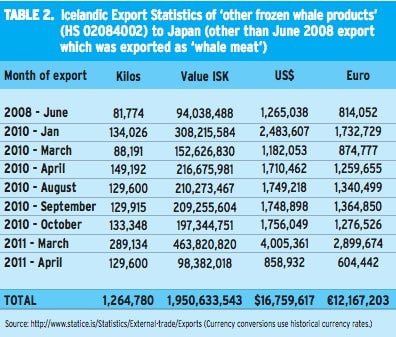

In 2010, Iceland sold around 500 tons (453 tonnes) of whale meat to Japan; by 2011 it had sold 900, despite some reduced fishing due to the earthquake/tsunami that hit Japan in March 2011. By mid-2011, Hvalur had brought in some $17 million in sales of fin whale meat and blubber in Japan, reports EIA. Sakuma estimates that it supplied around 20% of Japan’s whale meat market, as of May 2012.

As Ramage mentioned, Iceland’s success in Japan was likely due to its cheap prices. Its pricing power may in part be due to its catch: fin whales, which are the second-biggest animal on the planet. Japan hunts few, if any, of those. And the demand for fin whale meat displaced that of other types of whales.

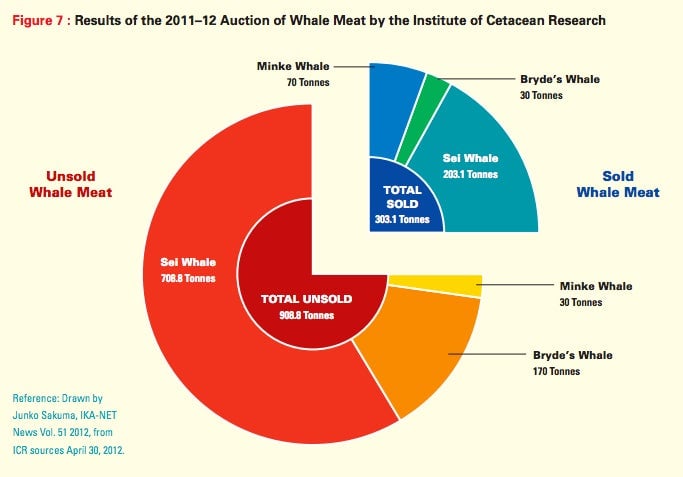

And fin whales are as much as six times more profitable than the minke whale, one of the standard Japanese catches. The Icelanders’ low prices and the glut of whale meat they’ve brought to the Japanese market have left Japanese whalers struggling to find buyers. In the last year, Japan’s ICR has tried selling its whale meat in well-publicized auctions. Here’s how well that’s gone:

Though Loftsson reportedly stopped hunting fin whales in 2012, Iceland’s increased fin whale 2013 quota hints that it might start exporting to Japan once again.

Even if it doesn’t, though, Japan’s whale meat oversupply persists. Now nearly 5,000 tonnes of whale meat (pdf, p. 2) is sitting in stockpiles, according to IFAW.

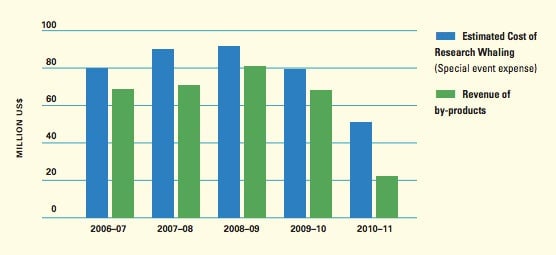

The question at hand is whether the government will bail out its whaling industry once again. It probably will: As the oversupply crisis set in, the government found new ways to funnel money to ICR, including via the earthquake/tsunami recovery fund. IFAW’s report found that the ICR has been sucking about $9.8 million each year (pdf, p.2) off the teat of government subsidies, on average. But in FY2011 it won $45.3 million from the government—and it was still in the hole. IFAW estimates that operational costs in 2010-11 were more than twice the amount of revenue it brought in.

This is all both ironic and revealing. Japan was one of the few strong supporters of Iceland’s controversial 2006 bid for the right to hunt whales commercially—probably without realizing that the country could undercut its own whaling monopoly.

Then again, maybe it would still have pushed for Iceland’s rights. After all, this is a country that consumes somewhere around one in every ten fish eaten in the world. And while that supply grows scarcer, waters are also increasingly monitored by international regulation.

As IFAW’s Ramage explains, preserving the right to do what it wants to animals in and around the ocean is one of the key agendas behind Japan’s bizarre supply-side whale meat economy.

“Along with the whaling issue, [the Japanese government is strongly opposed to issues like] the management of tuna fisheries, international proposals to protect sharks or even polar bears that come up at relevant international meetings—even if they don’t have a direct interest,” he says. “Unfettered access to marine resources on the high seas matters a lot to you if you’re a Japanese decision-maker.”