Adding ‘guru’ to your job title isn’t ridiculous when it’s earned

The title of “guru” was once reserved for religious teachers and spiritual guides. But today, the designation is deployed—without irony—by a plethora of corporate and creative professionals.

The title of “guru” was once reserved for religious teachers and spiritual guides. But today, the designation is deployed—without irony—by a plethora of corporate and creative professionals.

I was first alerted to the trend when I stumbled across the LinkedIn profile of a former colleague who had rebranded herself as a marketing guru. Next an environmentally conscious acquaintance asked me to write her bio, stipulating that I refer to her as a green guru. Then a fellow writer and educator sent me a link to her upcoming lecture. Her billing: literary guru.

My friends and colleagues are hardly alone. A quick search on the Internet reveals professionals who claim to be gurus in areas ranging from gossip and gourmet food to millennials, soccer and even Snapchat. What’s next—business magazines profiling the next generation of leaders as “Tomorrow’s Gurus?”

It’s easy to see the appeal of designating yourself a guru. It implies that you possess rare wisdom and insight, having accumulated a wealth of knowledge in a particular subject over a long period of study. It also imparts an aura of authority, suggesting that your every word is spoken ex cathedra and followed by the hoards.

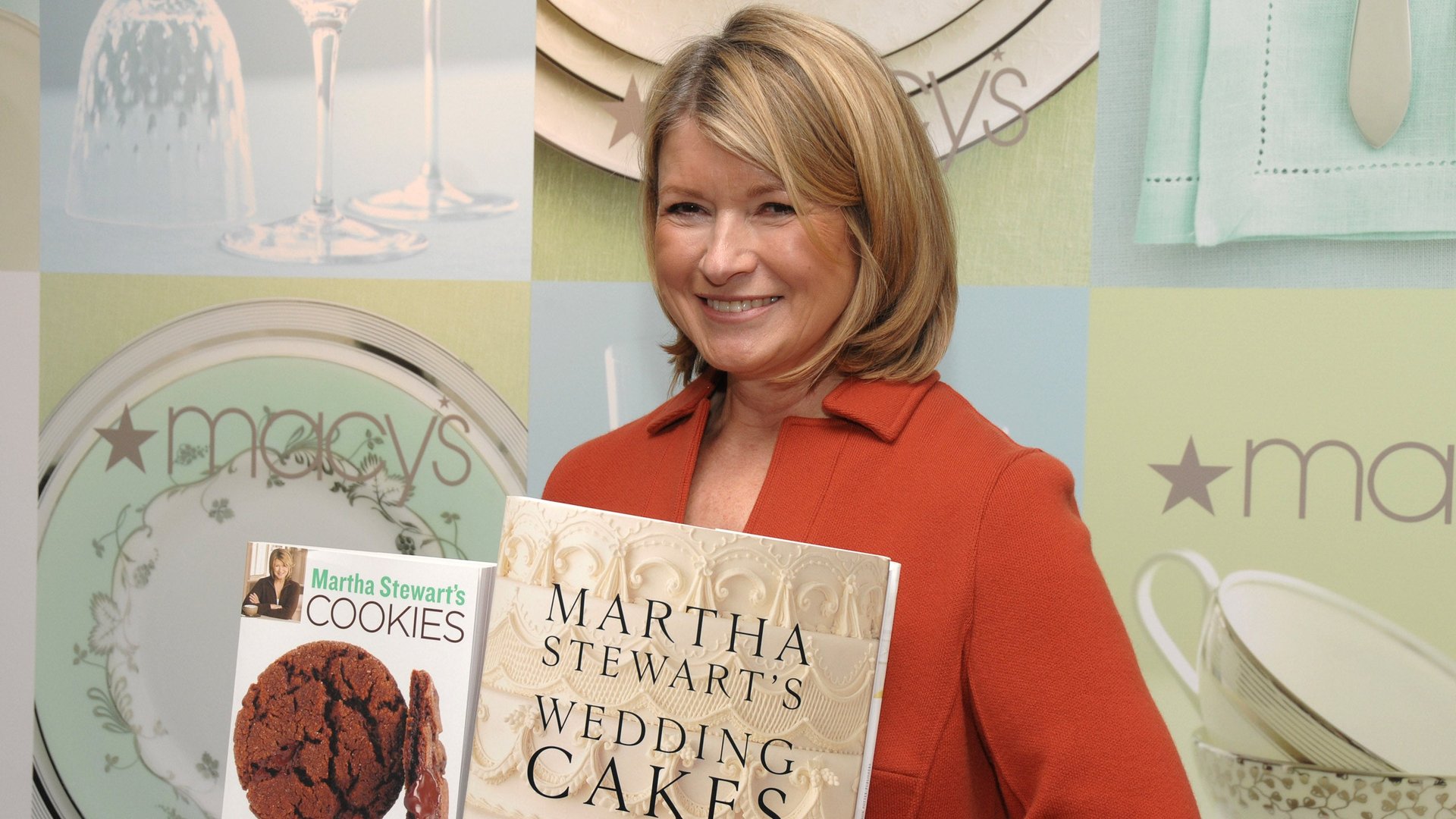

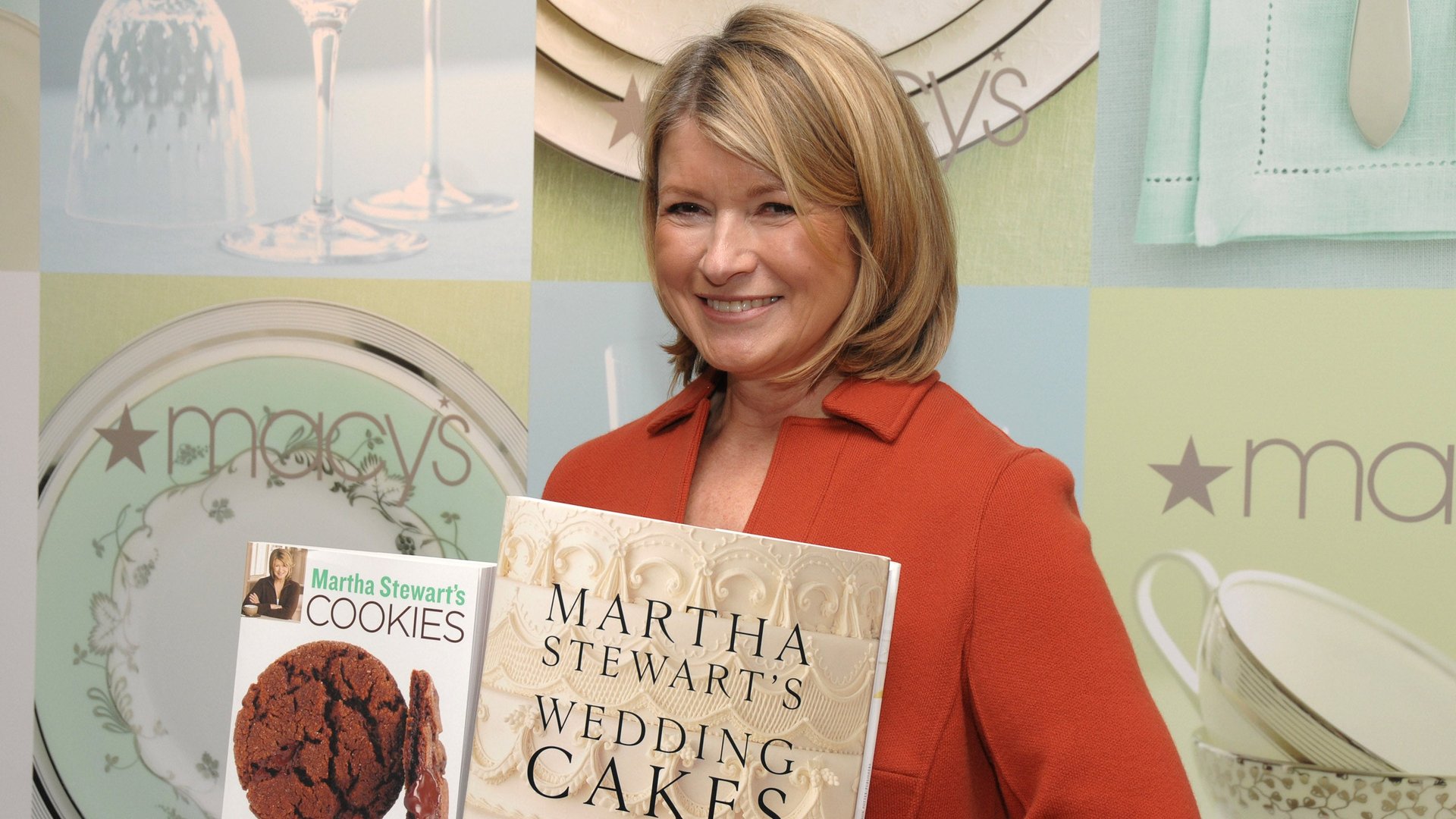

But what makes someone achieve true guru status? It seems fitting enough when a talk-show host introduces her next guest as “lifestyle guru Martha Stewart.” It sounds a bit grandiose for those of us who’ve yet to become household names with massive business empires.

Of course, the great thing about being a guru is that you don’t need anyone’s permission to snag the title. As far as I know, there’s no degree program. You don’t have to work your way up to the moniker through a series of promotions.

This lack of clarity makes the “guru” title open to ridicule. But it can be a pretty useful descriptor for people staking out careers in relatively new and evolving fields like social media, where accreditation matters less than expertise. And it can also make sense for people who have a lot of different jobs related to the same subject, like a “relationship guru” who runs a dating service, writes an advice column and holds regular conferences to help the lovelorn.

Still, in a cynical world, it’s important to think hard before you call yourself a guru. People will demand to know from whence your street cred has been procured, so you’ll need to be able to list actual accomplishments. You should also have a history of writing and lecturing about how you’ve achieved your goals in order to help other people accomplish theirs. Not only does this give you expert status, it also proves your selflessness—a key guru requirement. The more people who attend your lectures or follow your latest 140-character bits of wisdom on Twitter, the more right you have to add “guru” to your job description.

Usually known for jumping on the bandwagon, I’ve toyed with the idea of changing my own title. I sort of like the sound of “word guru.” Or maybe I could call myself a guru in several areas, each specific to my multifaceted career. In journalism, I’d be an essay guru; in advertising, I’d be a copy guru.

But I can’t quite get on board yet—at least, not with a straight face. Like many people in advertising, I struggle to promote myself. I admire (and am even a bit envious of) people who don’t have that problem.

For now, I’ll stick with calling myself a writer. I hope that my work, as well as my demeanor in dealing with other professionals, will eventually earn me the additional descriptors of leader, expert, and guide.

And if that doesn’t work, I guess I’ll have to find myself a career guru.