One of the world’s largest soft-drink markets has just defeated the soda lobby—again

In 2014, Mexico introduced a soda tax that cut annual sugary drink sales by 6% and has been hailed as a global example (including this month by the New York Times editorial board) of how to fight obesity.

In 2014, Mexico introduced a soda tax that cut annual sugary drink sales by 6% and has been hailed as a global example (including this month by the New York Times editorial board) of how to fight obesity.

Recently, though, Mexico’s legislators started to backtrack. On Oct. 19, the country’s lower house of Congress agreed to reduce the 10% tax, equal to 1 Mexican peso ($0.06) per liter, to a 5% rate on drinks with 5 grams or less of added sugar per 100 milliliters. (A can of regular Coke contains around twice that amount.) The rationale was that the reduced tax rate for all but the most sugary drinks would encourage soda companies to reduce the sugar content in their products.

The public response was swift and harsh. Public health advocates accused the government of siding with soda companies at the expense of Mexican children. A 300-milliliter bottle of flavored water, the most common size, still contains three teaspoons of sugar, about one less than the total daily limit recommended for children by the World Health Organization, they said in a statement (link in Spanish).

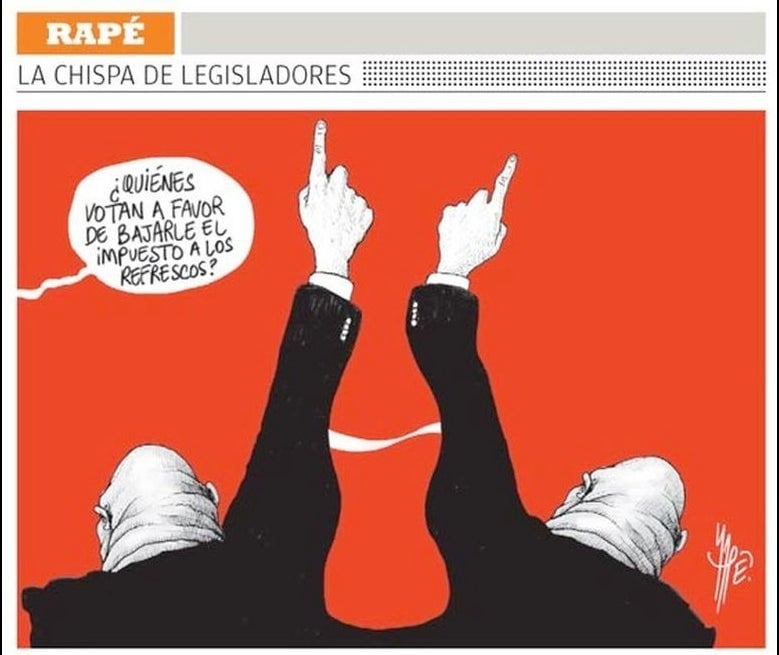

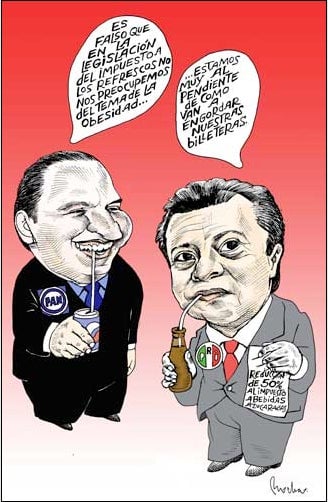

Political cartoonists had a field day drawing politicians as pawns of Big Cola.

“Who votes in favor for cutting the soda tax?”

“It’s not true that in legislating the soda tax we don’t worry about obesity…”

“…We’re very interested in how our wallets will get fatter.”

“Was obesity going down?! No, what’s going down is the soda tax…”

So on Oct. 29, the Senate cancelled the tax reduction.

Mexico wasn’t the first country to impose a soda tax. France has been taxing soft drinks since 2012, but the French have never been big soda fans, relatively speaking.

Mexican households, in contrast, consume the largest amount of carbonated drinks in the world. In 2013, when the tax was passed, they gulped down nearly 550 liters, according to data from Euromonitor International. As the world’s third-biggest soda market, Mexico’s tax represented the first real battle—and victory—over a policy that public-health experts have long advocated for.

“The tax has much more meaning in Mexico,” Barry Popkin, a nutrition professor at University of North Carolina, told Quartz. “It’s health impact will be much greater.”

He and other researchers from his university along with Mexico’s National Public Health Institute calculate that aside from reducing soda sales, the tax increased purchases of non-taxed beverages, mainly bottled water, by 4%.

Mexico’s tax has already spurred discussions about how to reduce soda consumption in other countries, including Chile, Ecuador, and Peru, Popkin added. And researchers have studied the clever public health campaign that led to its approval to find clues on what might work elsewhere.