Highlights from the peerless 164-year-old World’s Fair, before it closes this week

For the past six months, this year’s World’s Fair has quietly hummed along as an autonomous city on the outskirts of Milan. Spread across an area about the size of Monaco, some 200 buildings (representing 145 countries), plus parks, rivers, restaurants, museums and even a security force gave breadth to the event, also known as Expo Milano, while a daily roster of cultural shows, food tastings, and talks animated themes of nutrition, food scarcity and sustainable consumption.

For the past six months, this year’s World’s Fair has quietly hummed along as an autonomous city on the outskirts of Milan. Spread across an area about the size of Monaco, some 200 buildings (representing 145 countries), plus parks, rivers, restaurants, museums and even a security force gave breadth to the event, also known as Expo Milano, while a daily roster of cultural shows, food tastings, and talks animated themes of nutrition, food scarcity and sustainable consumption.

Interested? It’s almost too late: On Saturday, Oct. 31, the Expo will go dark. In a few weeks, the entire fairgrounds will be dismantled.

Not a moment too soon, for some. Before Expo Milano opened in May, violent demonstrations erupted in the streets of Milan, with protesters framing the event as a colossal waste, plagued by corruption. Later, critics dismissed the expo as a spectacle without substance.

But perhaps their cynicism is misplaced—yes, the Expo (also known historically as the World’s Fair or Universal Exposition) is sprawling, expensive and complicated; but to understand it today, you have to consider its full offering, beyond the politics and infrastructural gaffes.

The Expo was never designed to be a tightly-curated gallery of culture. “Exposition” is a loose term, perhaps even more so this year. The 2015 Expo is a jubilant mess, a curious, food-themed open-sourced event with a thousand cooks and contributors from around the world. Every pavilion is new terrain, with its own set of rules and traditions. To fully experience the Expo is to lose yourself in queues and chaos.

What happened to the World’s Fair

Starting in London in 1851, World’s Fairs used to be the main venue for nations and businesses to unveil their latest technological and design marvels. The telephone, the ketchup, electrical outlets, the Eiffel Tower, the diesel engine, broadcast television, and even Picturephone, the precursor to video conferencing, were all introduced at world’s fairs.

“By serving as a display point for art and industry, countries were forced to assess their own standing within these categories,” says design history professor Russell Flinchum to Quartz, explaining that the expo was once as prestigious an international event as the Olympics.

Now that companies like Apple, and Microsoft have the ability to mount their own mega-spectacles and command the world’s attention, the Expo has lost its place as the world’s singular stage for unveiling innovation. Over the decades, the very concept of “world’s fair” or “world expo” has been watered down—there are now “world expos” dedicated to everything from tanning to drones to whiskey.

What makes Expo Milano unique

But even though the next iPhone release or Tesla model will likely not be unveiled at the next world expo, the event that takes place every five years still presents an unrivaled sampling of nations.

On the Expo’s main thoroughfare, a parade of spectacular buildings vie for attention. The Polish pavilion, with the hidden mirrored garden is within steps of the awe-inspiring display at the French pavilion where objects hang from the ceiling like fruits begging to be plucked. Throughout the vast fair grounds, design takes a front seat not just in the architecture of pavilions but also in the incredible array of displays, films, activities and programming within them.

These range from sublime high tech visualizations like in the Chilean exhibition where the one can trace how food travels with a marvelous touch screen installation, to analog interventions like the swings in the Estonian building that generate electricity.

The visitor experience is indisputably uneven, and that’s precisely the point. Germany’s incredible multi-sensorial “Field of Dreams” production and UN’s monumental Zero Pavilion masterpiece can co-exist in the same place as the more modest box gallery displays representing Tanzania, Panama, or Grenada. Depending on how you design your route, you can transition from one to the next quite nicely.

Commerce culture

Much criticism has been hurled towards the commercialization of this year’s expo, particularly in light of its theme “Feeding the planet, energy for life,” which highlights sustainability and nutrition. Critics decried the presence of a McDonald’s “pavilion” (really just a restaurant) and the Lindt chocolate shop on the main thoroughfare. Magnum ice cream carts offended foodies with mass-produced ice cream in the homeland of artisanal gelato.

But from the beginning, World’s Fairs have always involved commercial brands. Historically, corporations like Ford, IBM, and Coca-Cola made significant contributions in the fair’s lore. In the 1964 New York World’s Fair, Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen conjured an egg-shaped pavilion for IBM that gave thousands of visitors an indelible immersion (video) in the future of computer technology.

Among the most educational exhibitions this year is the Cibus è Italia pavilion representing Italian food manufacturers. An unassuming warehouse in the back of the fair packs a staggering number of Italian brands involved in producing olive oil, ham, cheese, pasta, chocolate, flour, wine and food packaging. Room after room, visitors begin to appreciate the art, science and tradition behind those food products in our pantry.

In another corner of the fair, Coop’s Supermarket of the Future, a technological wonder with a fruits-sorting robot and intelligent touch screens is among the fair’s memorable highlights.

Commerce is contemporary culture, and is part of the DNA of the expo. It’s worth noting, too, that few complained about those refreshing Pimm’s cups being sold in the UK pavilion, the public benches paid for by Fiat, or the free Beluga caviar in the Russian pavilion.

Crossing paths

It’s true that some smaller pavilions look like crude roadside souvenir shops—cluttered with a mess of wood carvings, beads, food products, found objects and obligatory travel posters. But even makeshift museums offer an occasion to meet someone from each country.

“For over 160 years, World Expos have helped humanity make sense of change and navigate through difficult times by promoting education, innovation and cooperation,” states the The Bureau International des Expositions, the intergovernmental body that regulates world expos. At a time when deep, violent chasms over ideological differences dominate headlines, perhaps the world needs this fair more than ever.

In the Expo Milano, I was able to “visit” conflict hot spots like Somalia or Congo. One of the most unforgettable experiences I had was in the Palestine pavilion, where a precocious nine-year old boy guided me through an interactive display of sites, including his local mosque. Flipping through the pictures, he explained to me: “I’m Muslim and you’re not, I think that’s okay.”

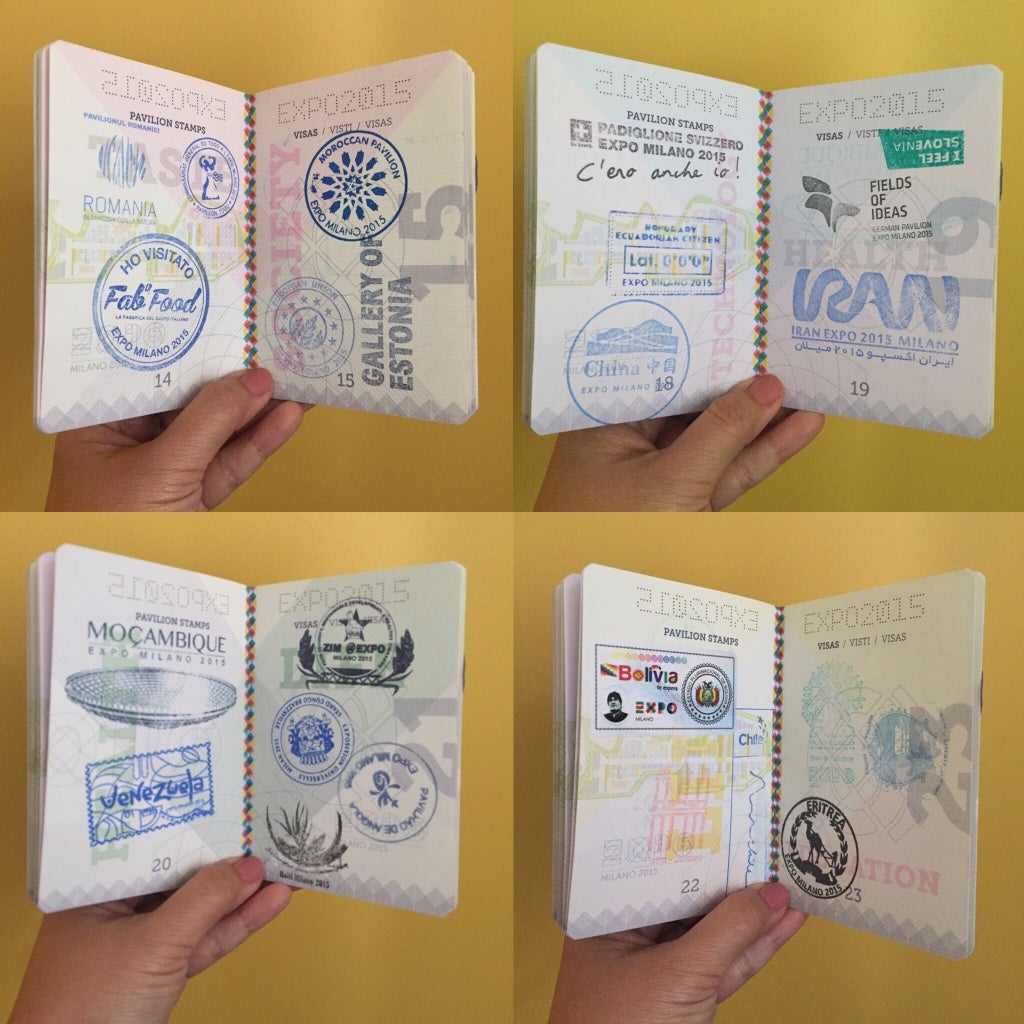

The souvenir I treasure most from the Expo is a passport that you can buy at the entrance and fill with stamps as you visit each pavilion. The unique graphic design of each stamp (or sticker, thanks Bolivia) is a charming throwback to the days when countries invested in elaborately designed visas and beautiful diplomatic seals.

Flipping through my Expo passport today makes me think of our mishmash national identities, determined no longer only by our birth place but tossed in with the places we’ve visited, the people we meet, the clothes we wear and the food we eat.

Even if the World Expo succeeds only in arresting our flaring agoraphobia and plants a seed of curiosity for each other’s culture and condition, then it’s an event worth holding—and attending—for years to come.