From Ankara to Louisville, from Tel Aviv to Ottawa, pollsters keep getting it wrong

The world’s political pollsters are having another bad week. In Turkey, local polling firms were wrong-footed by president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who confounded their forecasts by winning a resounding majority in parliamentary elections on Nov. 1. American pollsters also got it wrong 5,800 miles to the west—they forecast a Republican defeat in Kentucky’s Nov. 3 governor’s race, and instead the party’s candidate won.

The world’s political pollsters are having another bad week. In Turkey, local polling firms were wrong-footed by president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who confounded their forecasts by winning a resounding majority in parliamentary elections on Nov. 1. American pollsters also got it wrong 5,800 miles to the west—they forecast a Republican defeat in Kentucky’s Nov. 3 governor’s race, and instead the party’s candidate won.

In fact, the whole year has been horrible if you happen to do political polling for a living, or are simply interested in tracking the direction of coming races: In March, polls overwhelmingly—and wrongly—forecast an election defeat for Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu, who resoundingly won. In May, they got the British elections wrong. In Greece, they were wrong twice this year—first in a July referendum on prime minister Alexis Tsipras’ austerity policies, and then in a September parliamentary election (although to be fair to the pollsters, Tsipras almost seems to go out of his way to turn expectations on their head). In October, it was Canada’s turn to deliver an election-day surprise.

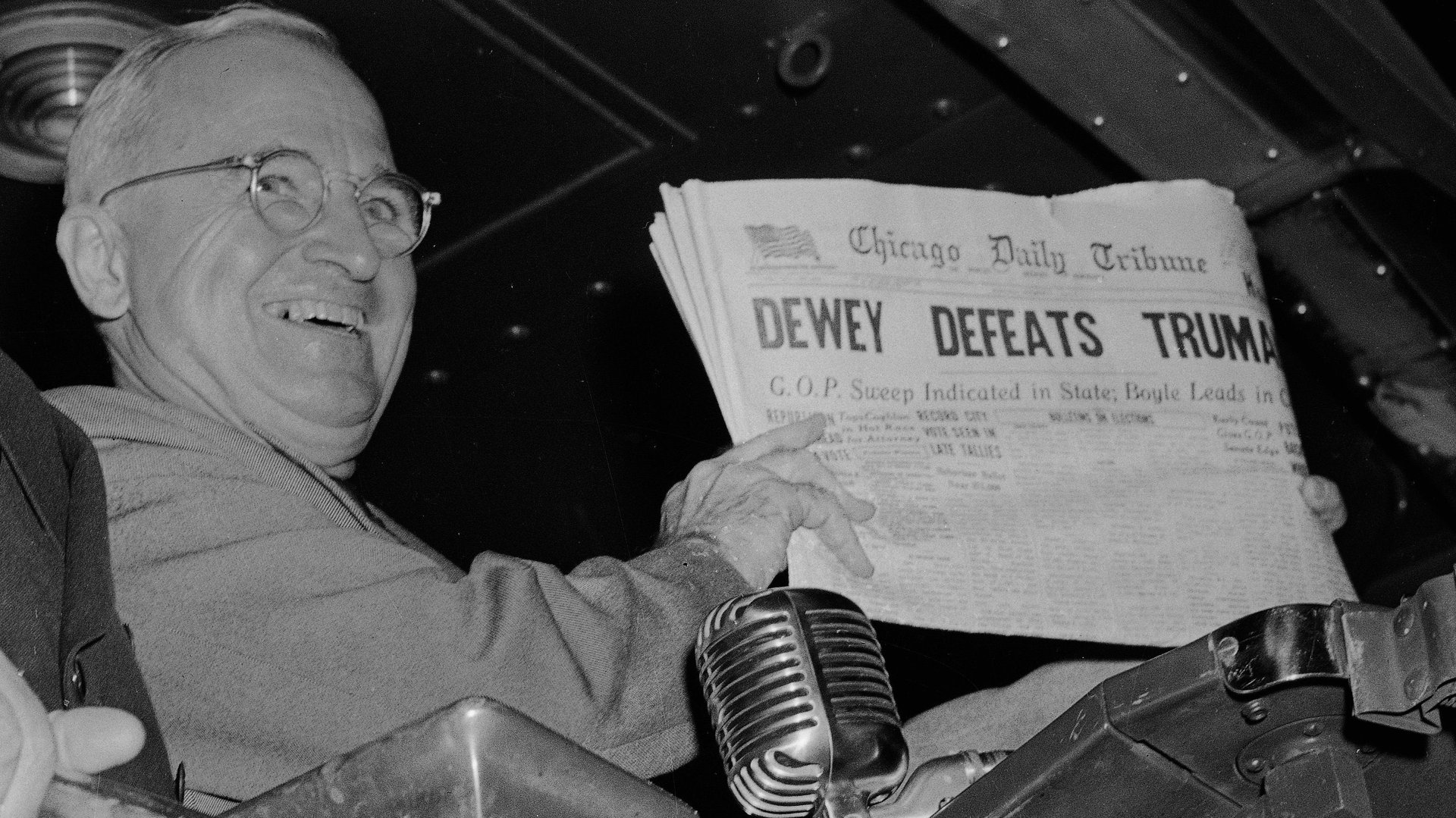

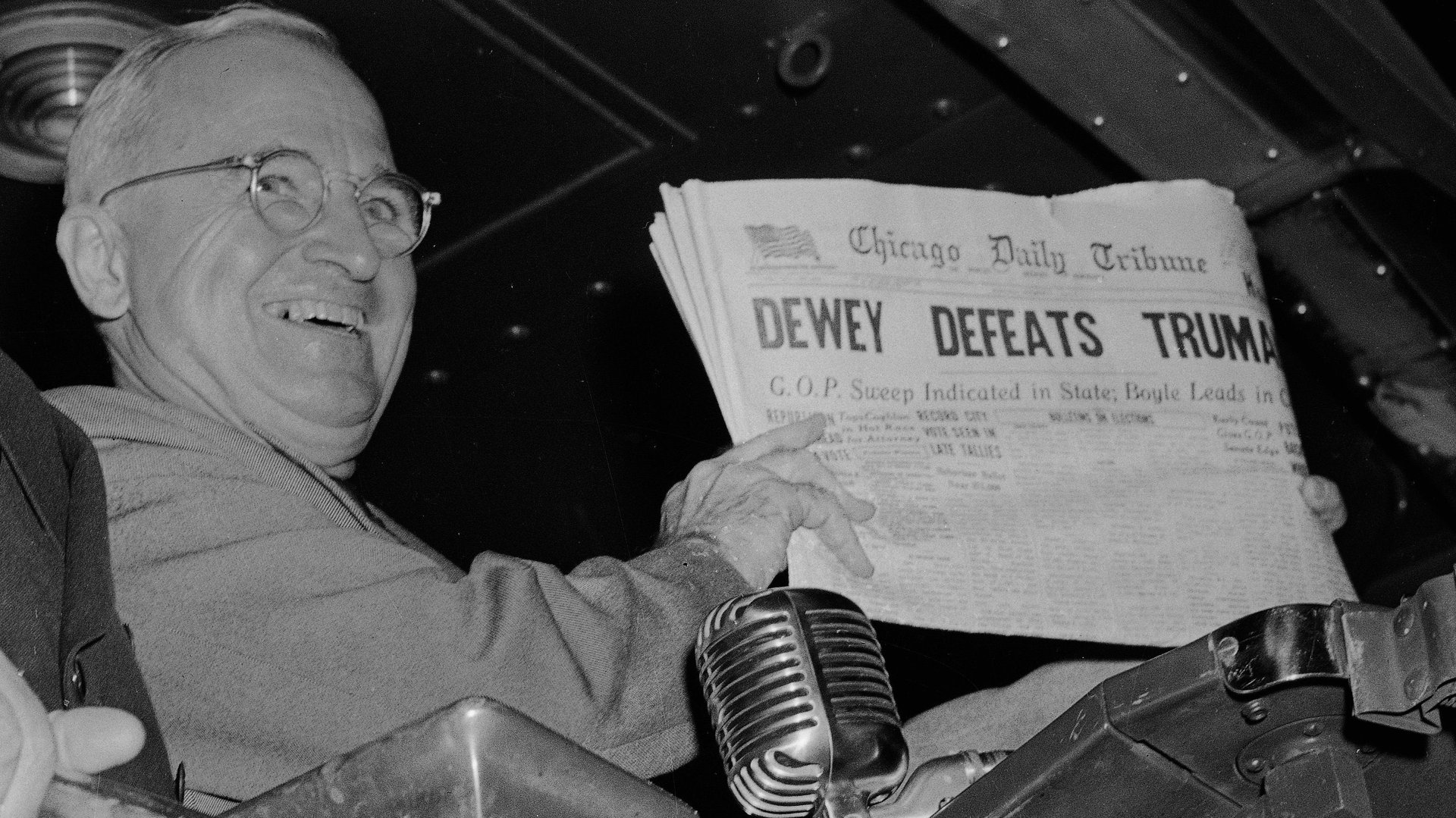

All of this was foreshadowed in 2014, when the polling consensus misforecast the mid-term US elections (although few missteps could compare with what happened in 1948, when some media were so convinced by polls incorrectly projecting Thomas Dewey beating Harry Truman in the US presidential election that they printed the outcome ahead of time).

In almost any other numbers-based industry, such a record of wrongness would be a crisis—it no doubt factored into Gallup’s decision to sit out the 2016 US presidential primary races. Yet polls keep being produced, and people keep hungering for them. For a variety of reasons, we just want to know what’s going to happen next, and not wait for events just to occur on their own.

A lot of people have relied in particular on Nate Silver

Dubbed by one writer the “election oracle” after correctly calling the 2008, 2010, and 2012 US elections, Nate Silver has made a career of savaging non-data-savvy pundits who don’t derive their forecasts, as he does, from a proprietary algorithm that averages and tweaks political polls. As the founder of FiveThirtyEight.com, Silver has seemed to hate such neanderthals, and they have hated him right back.

Silver didn’t respond to an email. But in a post today, his FiveThirtyEight colleague Harry Enten said it’s premature to conclude that “polling [is] broken and not to be trusted.”

“Surveys can still be informative,” Enten wrote, “but should never be taken as gospel.”

Silver himself groused in June that “polling is getting harder.” That was a month after his newsroom’s bad forecast of the UK election, when he said, “It’s become harder to find an election in which the polls did all that well.”

Back then, Silver blamed a number of possible reasons for the industry’s awful performance—and flagged more bad forecasts ahead:

Perhaps it’s just been a run of bad luck. But there are lots of reasons to worry about the state of the polling industry. Voters are becoming harder to contact, especially on landline telephones. Online polls have become commonplace, but some eschew probability sampling, historically the bedrock of polling methodology. And in the US, some pollsters have been caught withholding results when they differ from other surveys, “herding” toward a false consensus about a race instead of behaving independently. There may be more difficult times ahead for the polling industry.

Excellent call.