Bush 41’s attack on his son’s war in Iraq heralds the end of the Bush dynasty

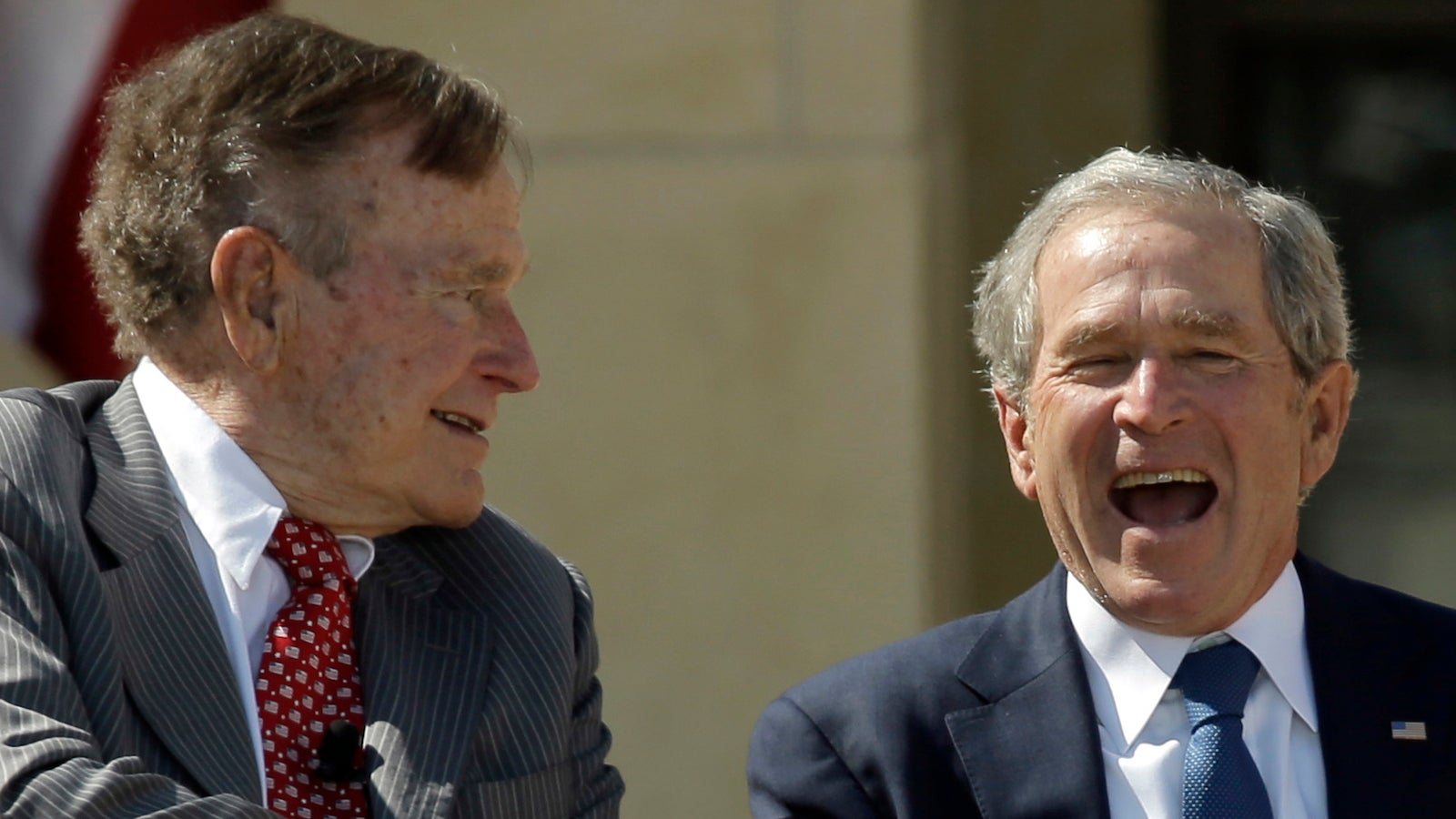

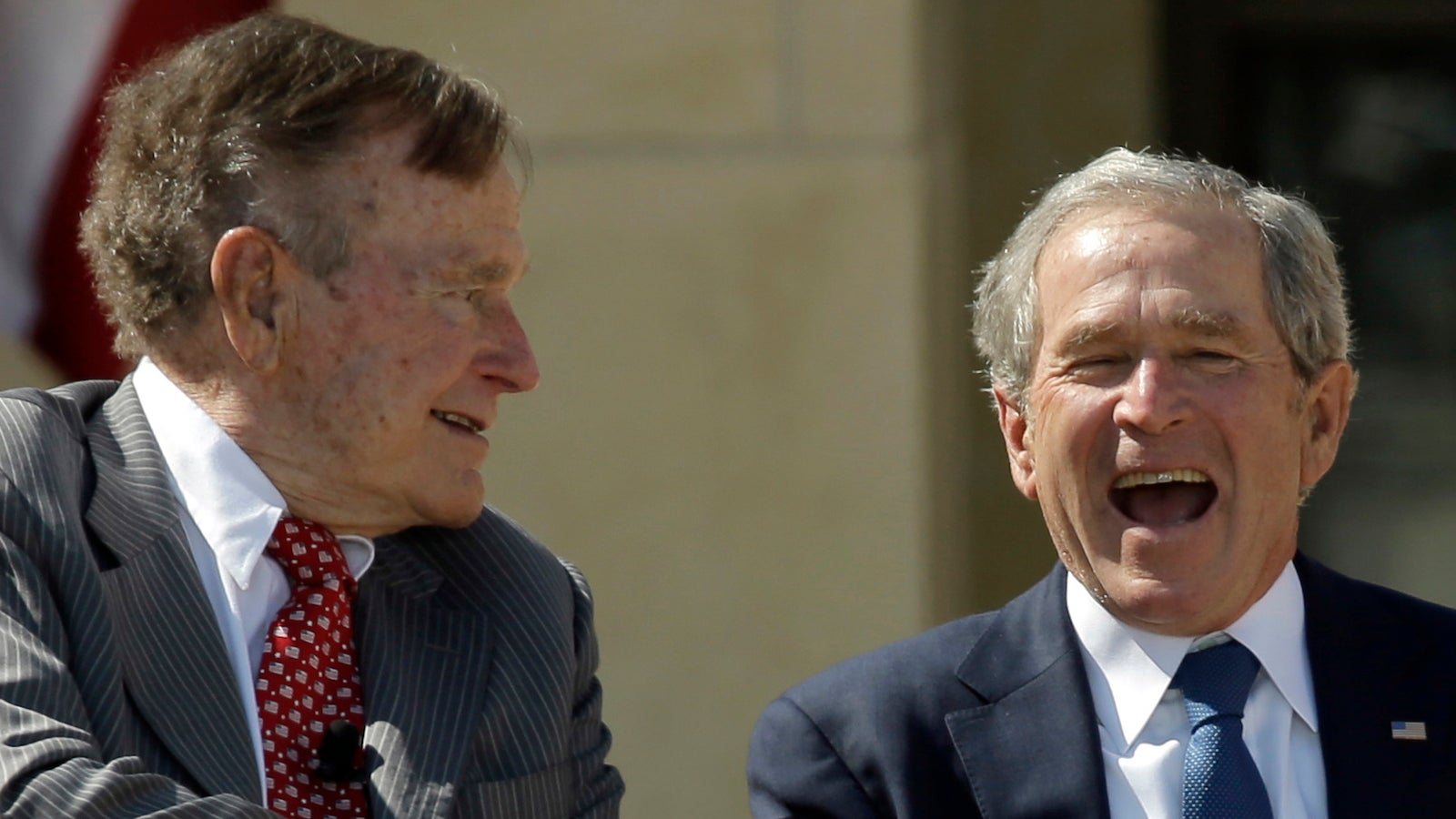

The famously tight-lipped George H.W. Bush lets slip some strong opinions in Destination and Power, the new John Meacham biography of the 41st American president. He expresses displeasure with the overheated rhetoric that his son used to describe America’s adversaries after 9/11. He describes former vice president Dick Cheney and his allies as “real hard-charging guys who want to fight about everything, use force to get our way in the Middle East.” The former president also has some harsh words for Donald Rumsfeld, who he says possesses an “iron-ass view of everything.”

The famously tight-lipped George H.W. Bush lets slip some strong opinions in Destination and Power, the new John Meacham biography of the 41st American president. He expresses displeasure with the overheated rhetoric that his son used to describe America’s adversaries after 9/11. He describes former vice president Dick Cheney and his allies as “real hard-charging guys who want to fight about everything, use force to get our way in the Middle East.” The former president also has some harsh words for Donald Rumsfeld, who he says possesses an “iron-ass view of everything.”

These comments suggest the elder Bush is aware that the war in Iraq came at a cost to his son’s legacy. One wonders if he knows just how badly the first war in Iraq damaged his own—or if he’s considered that Jeb Bush seems likely to be caught up in the same curse.

Bush’s attitude toward his son’s war is not a total surprise. Some of his closest advisors had already been openly critical of it. Brent Scowcroft, national security advisor from 1989 to 1993 and close confidante to the elder Bush, penned a blistering August 2002 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal warning that “any campaign against Iraq, whatever the strategy, cost, and risks is certain to divert us for some indefinite period from our war on terrorism.”

But Bush’s comments are more meaningful because they come from the perspective of a father as well as a former president who saw the price of using military force in this region.

On the face of it, the elder Bush had the greatest success in his handling of Iraq. Operation Desert Storm, launched when Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, succeeded in defeating Iraqi forces and driving them out of the country.

But the American public was wary of Desert Storm, one of the first major military operations since Vietnam. Pollster Louis Harris noted, “The underlying attitude about the Gulf is distinctly against the expenditure of American lives.”

To overcome what he called the “Vietnam Syndrome,” Bush deployed dramatic rhetoric, calling Hussein one of the greatest threats in the world.

“We’re dealing with Hitler revisited,” he said in October 1990. His aggressive public-relations campaign prompted him to take on protesters who argued that the US operation was all about oil. “The fight isn’t about oil,” he said, “the fight is about naked aggression that will not stand.”

Iraq cost Bush dearly. When Hussein flouted United Nations resolutions and launched attacks on the Kurds, the glow over the US victory dissipated as opponents questioned the president’s long-term strategy. Conservatives attacked him for being too timid, with the National Review urging him to “finish the job we started.”

At the same time, Democrats accused him of lacking any viable plan. “It’s like any other bully, you send ‘em mixed messages, they’ll take advantage of you every time,” then-Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton said. And Bush became so consumed with the war that he neglected the recessionary economy back at home, which gave Clinton a path to victory in 1992.

The Bush administration also failed to fully anticipate the anger that the continued presence of US troops would stir in the region, which would become a point of mobilization for the terrorist network al-Qaeda.

The next Bush presidency was also damaged by a war in Iraq. Initially, George W.’s war against terrorism was about destroying the Taliban regime and building a counterterrorism program to dismantle al-Qaeda.

But in 2002, Bush shifted course and decided to launch a major invasion of Iraq. Vice president Cheney, whose rise to power began when the elder Bush appointed him as Secretary of Defense, strongly backed this operation.

The younger Bush succeeded in toppling the Hussein regime. But the war turned into a major policy and political disaster. It became clear that the administration had not planned how to build a new and stable civil society in Iraq. The war dragged down the president’s approval ratings. His efforts distracted voters from his accomplishments against terrorist networks and opened room for a Democratic victory in 2008.

Today, with the rise of the Islamic State, Iraq has become a base of power for the very forces the US sought to defeat.

Now Jeb Bush is the latest member of the family to pay the price for the wars in Iraq. Memories of his brother’s presidency have haunted his campaign from day one. He’s spent much of his time distancing himself from his brother even as he struggles to find the right position when talking about foreign policy, providing shifting and contradictory responses on Iraq in particular.

The elder Bush’s comments criticizing the younger Bush administration’s handling of the second war in Iraq have arrived at exactly the wrong moment. Just as Jeb tries to re-energize his candidacy, the biography has reminded the nation about what went wrong when the last Bush was in office.

The Bushes have only themselves to blame. The father mobilized the public for a war with overheated rhetoric, only to dash expectations when the war came to an end with Hussein still in power. His son made the decision to deploy American soldiers and invest finances in a military operation that was not directly related to the main threats the U.S. faced.

The elder Bush may want to blame his son’s advisors for the disaster. But as Harry Truman famously said, the buck stops at the president’s desk.

There is a lesson to be learned from both Bushes’ experiences in Iraq about the enormous costs of using overheated wartime rhetoric to wield misguided military power. Although the elder Bush’s comments were meant to rehabilitate the family legacy, they very well might have the opposite effect by reminding the public how two generations of presidents mishandled this foreign policy challenge.