Thank you, Ben Bernanke, for ruining Australia’s economy

“Currency war” is a dirty term, because no one wants to admit they’re slyly devaluing their currency to gain a competitive advantage.

“Currency war” is a dirty term, because no one wants to admit they’re slyly devaluing their currency to gain a competitive advantage.

But most major economies—the UK, Japan, the US, among them—are printing money, which by definition depreciates their currencies. Down here in Australia, whether the depreciation is a nasty ploy to boost competitiveness, or whether it’s just a result of sensible stimulatory policy, is irrelevant.

Because little countries like ours, who have managed their economies reasonably well, become “victims” one way or the other. Currency depreciation from developed countries has a significant impact on our economy.

Back in 1964, author Donald Horne dubbed Australia the “lucky” country. He was being ironic, taking a shot at our provincialism and the “second-rate people” who ran us and shared in our luck. But we have genuinely been a lucky country recently. The China boom and spike in commodity prices made us richer: Australian income levels in the past decade rose by around 25% compared to Europe and the US.

Economists described the commodities-driven surge in terms of trade (the ratio of export to import prices) as a “free income gift to Australians.” I’ve witnessed this firsthand, like when the million-dollar home down the street was bought by an electrician. That couldn’t have happened 10 years ago.

It wasn’t all luck. In the 1980s, Australia introduced a series of tough economic reforms, including floating the Australian dollar, slashing import tariffs and liberalizing the financial system, which made us more competitive and efficient. But we’ve also been pretty disciplined in our spending: our ratio of government debt to GDP in 2012 was 22.9% (the US ratio just ticked over 100%).

It now, however, looks like the commodities boom is ending, at least the crucial “price phase”; the investment phase is also peaking. The economy has slowed. In the September quarter of last year, the economy grew just 0.5%, the slowest growth in 18 months and well below average of 0.9%.

In Australia we know this lesson well: When commodity booms end and prices fall the dollar usually also falls. But the Australian economy has an inbuilt shock absorber: the growth baton is handed from commodities to other sectors, like manufacturing and tourism, that benefit from the lower dollar.

This time around, that isn’t happening.

Commodities have slumped, but the dollar has stayed strong.

So while the mining boom is peaking and ending, the industries that are meant to take up the slack are hurting.

Why?

Because of Americans’ lower interest rates and money printing, a wall of money has hit Australia.

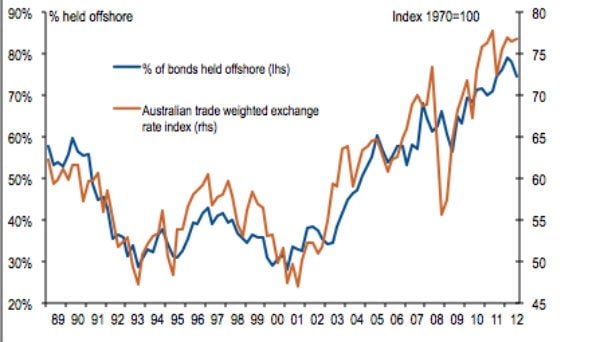

First it was central banks rebalancing portfolios and buying more dollar; more recently, it has been big investors chasing our higher yields and AAA credit rating: 75 to 80% of all Australian bonds are now owned offshore.

Along with foreign capital flowing in to fund the last days of the mining boom, that’s caused the dollar to remain high. It’s triggered significant pain in tourism, education and manufacturing.

To try and offset this, our central bank, the Reserve Bank of Australia, has been cutting rates too: it has cut official interest rates by 1.75% to 3% since November 2011.But that hasn’t worked either, and the dollar remains stubbornly high. The RBA is unlikely to take it a step further and intervene directly, as the Swiss Central Bank did, because it’s just too expensive.

The dollar could suddenly plunge; but with monetary policy from the central bankers up there likely to be expansionary for some time, the dollar is likely to stay strong. So our exporting and import-competing industries will have to make a very painful adjustment and become more efficient, and that means shedding staff leading to higher unemployment.

There are, of course, some benefits: imports are cheaper, which is allowing consumers to spend and keeping inflation down. Another silver lining in the pain: the economy and business needs a fresh round of economic reform to drive productivity.

But it would be nice to have that at a time of our own choosing, rather than being forced to because of economic mistakes made up there.