Blame New York City for the birth—and death—of your favorite foods

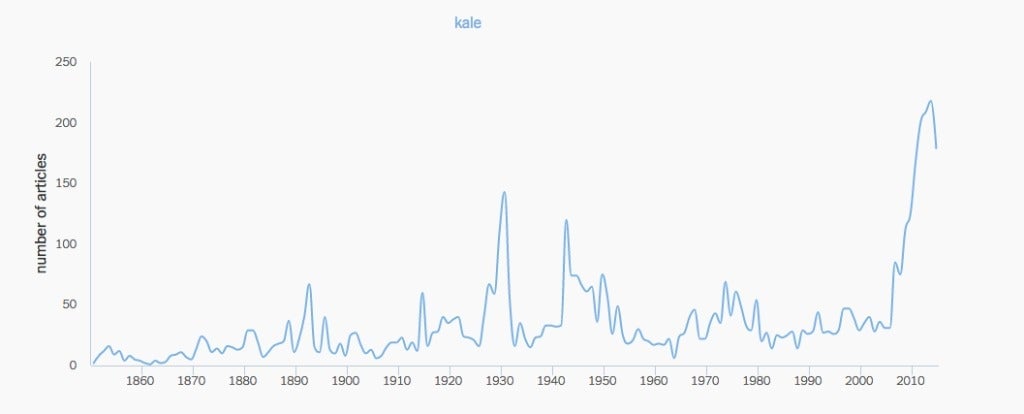

Remember the leafy garnish on salad bars in the ’90s? That was kale.

Remember the leafy garnish on salad bars in the ’90s? That was kale.

Just 10 years ago, the superfood rested in relative obscurity beneath our plates, rather than on top of them. Now, it has achieved celebrity status—showing up everywhere from Beyonce’s clothing, to cupcakes and cocktails.

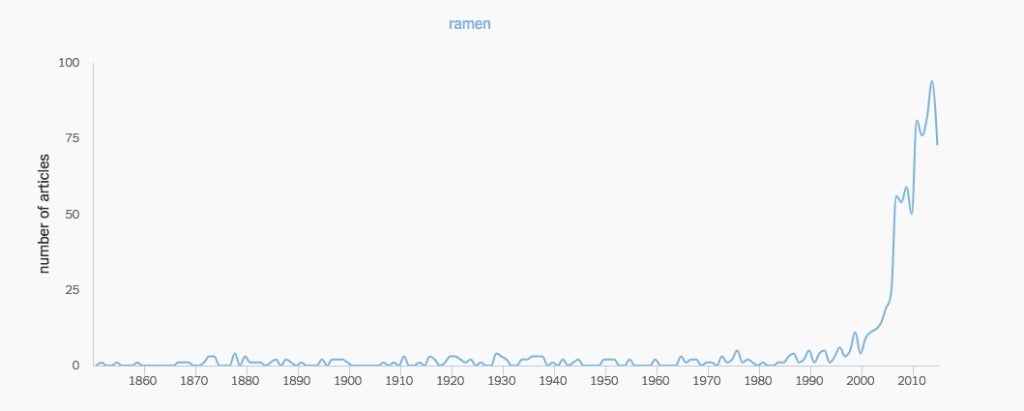

Ramen has enjoyed a similar elevated status in the past decade. Once served exclusively in a styrofoam cup, it became the centerpiece of ramen bars in Tokyo in the mid-aughts, and now hip ramen spots are ubiquitous in New York City.

So where do these food trends come from?

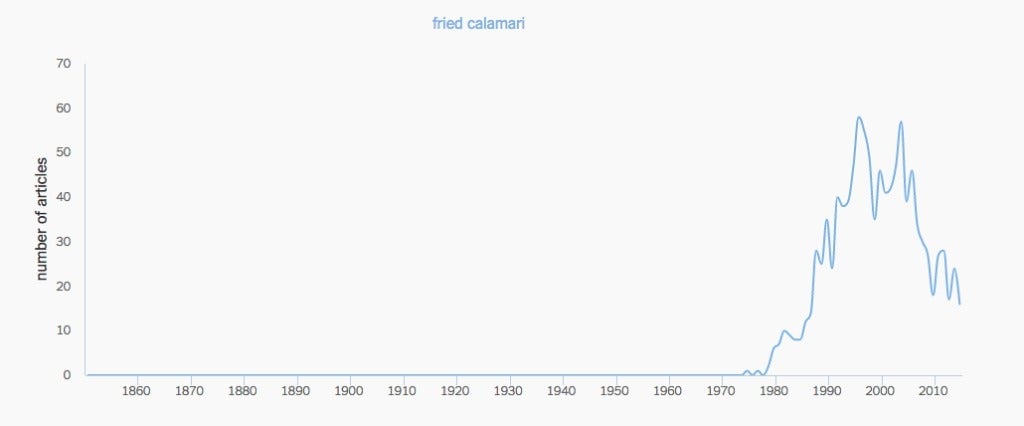

In a 2014 article in the New York Times, economics writer Neil Irwin developed a pseudo-scientific metric he termed “The Fried Calamari Index” to try to pin down the phenomenon. Using the Times Chronicle tool (essentially Google Trends for archived Times content) he found that the popularity of fried calamari in the paper peaked in 1996, with 58 articles mentioning the food that year. Using the Times as a source worked, since the New York food scene is “a bit ahead of the curve” (his words).

Fried calamari became popular in New York City’s top restaurants before filtering down into the rest of the country’s restaurants and eventually landing on menus at TGI Friday’s. As for kale and ramen, Erwin found: “their ascent to popularity, at least as reflected in the pages of The Times, was remarkably speedy.”

According to the Times Chronicle tool, the number of times ramen was mentioned in the paper began steadily increasing in 2004. An article in the Times that year titled “Here Comes Ramen, The Slurp Heard Round the World” announced the trend’s arrival based on a few ramen pioneers who had set up shop in the East Village. Chef David Chang, who opened his first ramen bar, Momofuku in 2004, was among them.

Kale began a similar ascent in 2007, according to the Times Chronicle.

In this 2007 article in the Times, the author orders a “raw kale salad” at Franny’s, an Italian farm-to-table restaurant in Brooklyn, expressly because she’s never seen one before. Two years later, trendy East Village restaurant Northern Spy Co started serving a similar raw kale salad, and in 2010 a recipe inspired by it showed up in the pages of the Times.

Francine Stephens, the owner of Franny’s, attributes their original kale salad composed of raw kale, raw garlic, chili flakes, lemon, olive oil and Pecorino Rosellino cheese to chef Andrew Feinberg. The salad was inspired, according to Feinberg, by a small dish featuring kale and Pecorino Romano created by chef Mark Ladner at Lupa, an Italian bistro Ladner opened with Mario Batali in 1999. Stephens recalls Feinberg’s salad as the first time she had ever seen raw kale used as the base for a dish.

Northern Spy Co put a kale salad composed of raw kale, roasted winter squash, lemon, olive oil, toasted almonds, aged cheddar and Pecorino cheese on their opening menu in the winter of 2009.

“Kale was having a little bit of a moment when we put ours on the menu,” Northern Spy Co’s co-founder Chris Ronis told Quartz. Within a year, the kale trend became a joke in the New York food industry, according to Ronis. “If a new place opened at anytime in 2011 and 2012, it was guaranteed there’d be a kale salad on the menu.”

The end of a food trend is a bit easier to identify. At the beginning of 2015, Chang pronounced ramen “dead.” A glance back at the Times Chronicle ramen chart bears this out.

The “end” of ramen, Chang speaks of, is not in fact an all out “end” so much as a stagnation. He claims “ramen is dead” symbolically, because chefs are no longer creating new versions of it. In it’s popularity, it has been driven to homogeneity. The way food is shared and viewed on the internet, Chang posits, has turned the craft of creating ramen—once an experiment—into a process of reiteration. “What’s happened to ramen is a microcosm of the larger food world,” Chang says, disavowing his signature dish.

A quick Google search for “Northern Spy kale salad” returns pages of the same recipe, reblogged, reposted, and repinned on every food-related internet source. Variations of the original show up on menus at cafes across the country.

“Our salad sort of tipped the scales and brought kale to the people,” Northern Spy Co’s Chris Ronis said.

Indeed, a raw kale salad is not the exotic treat it used to be. Franny’s took theirs off the menu years ago in favor of experimenting with new veggies, and a glance at the Times Chronicle chart for the number of articles mentioning kale shows the hype surrounding it is beginning to peter out.

But blaming the devolution of ramen—and, by extension, kale—on the internet is not quite right. If we go back to fried calamari, which showed up on the menus of New York’s finest restaurants well before the blogosphere and Instagram, we see that the fate of kale and ramen is the same as this once-fine food. While calamari’s rise in the Times lasted from 1980 to 1996, ramen is on it’s way out after 10 years, and kale is out after only about seven.

So goes the life cycle of popular foods: a burst of recognition, a blaze of repetition, and then abandonment when New Yorkers move on to the next hot dish.

A previous version of this post misnamed Neil Erwin as Neil Irwin and listed him as an economist. Image by Luxe TravelVisor.