Maker’s Mark learns a painful social media lesson, won’t dilute bourbon

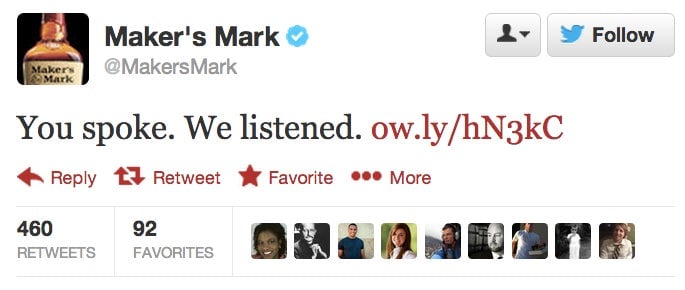

Maker’s Mark said today that it will not reduce the amount of alcohol in its bourbon after a weeklong backlash on social media chastened the famed distillery.

Maker’s Mark said today that it will not reduce the amount of alcohol in its bourbon after a weeklong backlash on social media chastened the famed distillery.

The reversal speaks to how brands often misjudge their relationship with customers, who can now vote more powerfully with their Twitter accounts than with their wallets. “What we’ve learned is that this is the customer’s brand,” Maker’s Mark COO Rob Samuels, grandson of the bourbon’s creator, said today in an interview. “It was an overwhelming response, we listened all week, and tomorrow morning we’ll immediately return Maker’s Mark to 90 proof.”

The company had emailed loyal customers on Feb. 9 to say it was lowering its proof to 84, or 42% alcohol, in order to address a supply shortage driven by bourbon’s surging popularity in the United States and certain other markets like Australia, Germany, and Japan. The announcement, first reported by Quartz, spread quickly in social media, rising from a small firestorm to an all-out backlash. The company defended itself in interviews, saying the taste wouldn’t change, but it didn’t help.

A useful comparison is Jack Daniel’s, which lowered the proof of its whiskey from 86 to 80 in 2004. There were plenty of complaints, but it was a different time: Facebook had just been created, Twitter didn’t yet exist, and that’s arguably why Jack Daniel’s is still distilled at 80 proof today. In the intervening years, plenty of brands, from Dell to United Airlines, have learned how social media can amplify customer complaints into corporate crises.

Still, look at this chart of the number of tweets about Maker’s Mark starting the day before the company announced it would water down its bourbon, using data from social analytics firm Topsy:

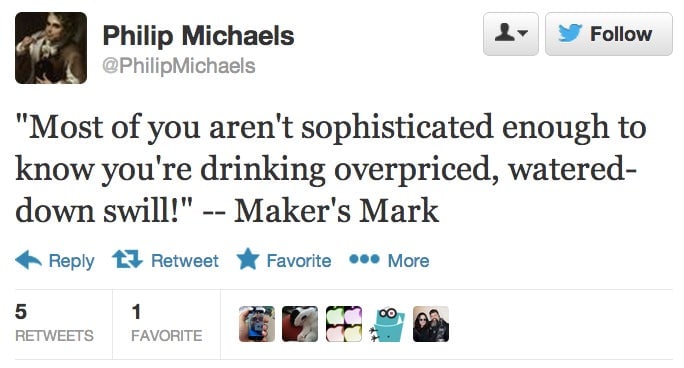

The Twitter backlash actually peaked on Tuesday, Feb. 12. Is it possible the company could have weathered the storm? Discussing today’s developments on Twitter, some people suggested Maker’s Mark had misjudged social media twice: first by under-anticipating the reaction and then by over-reacting to it.

Samuels said today in an interview that he continued to hear from customers all week, if not through social media then in emails and calls to their office. He said he attended a previously scheduled event last week at St. Elmo Steak House in Indianapolis, Indiana, where loyal customers were vocal about the change. “Let’s just say they didn’t hold back,” he said.

His father, Bill Samuels, a lawyer who eschewed the family business for years before taking over the distillery in 1980 and growing it into an international brand, was also pensive about the company’s rough week. He had maintained that reducing the alcohol in Maker’s Mark wouldn’t affect the taste of the bourbon that his father created in 1954 in Loretto, Kentucky, where it is still distilled, and said taste tests with customers had proven it.

“Clearly, if we would have just gotten a bunch of customers together and said, ‘Do you want us messing with your bourbon in any way?’ we would have gotten a resounding no,” Bill said. “So in a sense, we were asking the wrong question.”

Maker’s Mark was independently owned until 1981, when it began falling into the hands of increasingly large conglomerates, ending up in 2011 as part of Fortune Brands, which also owned seemingly random companies like Master Lock and Titleist, the golf equipment retailer. That corporate structure has tested the bourbon’s branding as a family-owned distillery committed to “small batch” production. In 2011, Fortune spun off its spirits brands into a publicly traded company, Beam Inc., which also makes the cheaper bourbon Jim Beam.

Neither Rob nor Bill would comment in detail about Beam’s involvement in the original decision to water down Maker’s Mark or today’s about-face. “They’re in full agreement as we reverse this decision,” Rob said. In recent earnings calls, Beam executives have warned that supply shortages could keep it from speeding up sales growth, especially in promising markets like South Korea, which in 2011 eliminated a 20% tariff on bourbon imports.

Without water as a tool to stretch its supply and with the bourbon having to age a minimum of six years before reaching customers, Maker’s Mark is left with few options. It could increase prices, as many argued it should, though it has already done that over the past several years. The company is also making capital investments to increase its production capacity in Loretto, but that will take at least four years to have an effect on supply.

As for the 84 proof Maker’s Mark, a small amount of it was created and sold to distributors before the company decided to return to 90 proof. “We think a lot of those bottles will become collector’s items,” Rob said.