A mass extinction once replaced giant fish with tiny ones—and it could be happening all over again

When big fish that dominate the seas suddenly disappear, small fish take over—and stay on top for hundreds of millions of years. At least, that’s what happened after a mass extinction some 359 million years ago. Thanks to overfishing, scientists worry it could be happening again.

When big fish that dominate the seas suddenly disappear, small fish take over—and stay on top for hundreds of millions of years. At least, that’s what happened after a mass extinction some 359 million years ago. Thanks to overfishing, scientists worry it could be happening again.

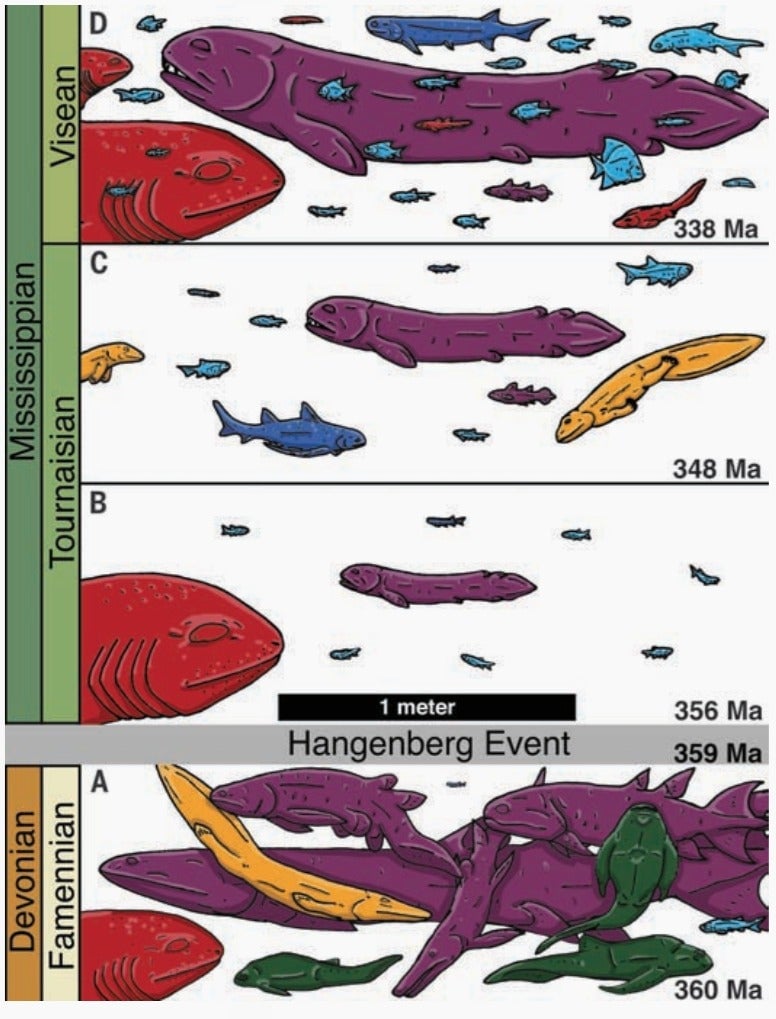

That grim prediction comes from a new study in Science (paywall) analyzing the effects of something called the Hangenberg Event—the closing chapter of the fourth of those five mass extinctions you’re always hearing about—which blotted out 97% of vertebrate species.

Up until that point, a diverse cast of gigantic fishes—many the size of school buses—ruled the seas, gobbling up small fish. After the mass die-off, though some big fish lingered, nearly all eventually died out. The creatures that repopulated the seas instead were much tinier than before, many of them shorter than a ballpoint pen. For another 40 million years, these little guys overran the oceans.

The cause of this ancient body-size shift has long stumped scientists. Past studies have surmised that warmer temperatures or lower oxygen might shrink fish after mass extinctions.

However, by analyzing more than 1,200 fossils from before and after the Hangenberg Event, the researchers concluded that natural selection was solely responsible—a finding that has ominous implications for how humans are warping ecosystems today.

We don’t know what exactly caused the Hangenberg Event, but the researchers have a clearer sense of its likely results. After the extinction hit, big fish briefly had the upper, er, fin: Their longevity and their ability to forego food let them tough things out.

But big fish are lousy breeders—the few offspring that they produce depend on their parents for survival. That means they adapt slowly. Because smaller fish reproduced quickly, they outcompeted bigger fish for resources and adapted more quickly to new environment. Big fish couldn’t keep up. With fewer and fewer predators around to eat them, the speedily breeding small fries thrived all the more.

Though big species like whale sharks and oarfish eventually emerged among their offspring, even these never rose to rival the small fish. As for the pre-Hangenberg behemoths, lungfishes are their lone remnants, says Lauren Sallan, paleobiology professor at the University of Pennsylvania and lead author of the study.

When the mass extinction reshuffled the balance of the big fish and the small ones, it changed how natural selection worked, tilting the balance so the Davids out-survived the Goliaths.

Humans are now doing something unsettlingly similar, says Sallan. Many of the 80 million tonnes of wild-caught fish (pdf, p.10) we eat each year are the big ones—cod, tuna, halibut, to name a few. Others that don’t show up on your sushi menu—sharks and rays, for instance—often die tangled in nets meant for other species.

Of course, it seems a little hyperbolic to liken industrial fishing to a planet-wide “mass extinction.” But the cause doesn’t much matter, says Sallan. “The point is that losses of this magnitude take millions of years to recover from and alter ecosystems long-term—no matter how the deaths occurred,” she says.

Lead image is by Matt Kieffer via Flickr (licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0; image has been cropped).