It’s no coincidence that terrorists keep targeting France

Even before the Islamic State claimed responsibility for the attacks in Paris, I knew what they would say. They would claim that France is a “crusader nation”; that France’s Muslims are oppressed; that France participates in operations against ISIL and has deep historical ties to the Muslim world.

Even before the Islamic State claimed responsibility for the attacks in Paris, I knew what they would say. They would claim that France is a “crusader nation”; that France’s Muslims are oppressed; that France participates in operations against ISIL and has deep historical ties to the Muslim world.

In the days and weeks to come, I am sure analysts will invoke France’s marginalized Muslim population, many of whom hail from countries that France long occupied. They might point to an aggressive secular culture, which singles out the practice of Islam. They could draw on the stigmatization of hijab, the ban on niqab, the elimination of halal food options in some public schools, the abandonment of the banlieus, the mocking tone of a condescending mainstream culture, and the exclusion of Muslims from political life.

These issues are worth paying attention to. To be abundantly clear, these neither explain nor justify the attacks. But they help explain why France is so repeatedly targeted.

One of the most influential jihadist texts is a work called The Management of Savagery, which outlines the jihadist strategy for bringing about the political goals they desire. (Hint: It’s in the title of the work.)

In the seventh issue of ISIL’s magazine Dabiq, shared last night on Twitter by author and analyst Iyad El-Baghdadi, the Islamic State expands on these themes, calling for a clash of civilizations. Jihadists are threatened by democracy, but they are empowered by narratives of sectarianism, mistrust and discrimination. Jihadists are not just becoming savvier at manipulating media, but at using attacks to advance their strategy of “exclusion.”

They find a major fault line, seek to undertake an attack that will widen this fissure, and reap the whirlwind as people in divided societies run in opposite directions.

We have seen this strategy used repeatedly as recently as the past few weeks.

In Beirut, two ISIL suicide bombers targeted a Shia neighborhood in southern Beirut. Lebanon is already strained by sectarian rivalry. The attack angers Lebanese Shia—with good reason—but also puts Sunnis on the defensive. These Sunnis may very well condemn the attack, and sympathize with their Shia co-nationalists. But they might also be skeptical of how this attack could embolden the Shia extremist group Hezbollah, which after all has engaged in the same kind of violence as ISIL, albeit with different targets.

In Turkey, ISIL is suspected of attacking a Kurdish peace rally, seeking to worsen relations between the country’s two principal ethnic groups, which were already suffering. In the Sinai, ISIL may well have taken down a Russian jet, further undermining an already unpopular Egyptian regime. This will reinforce a cycle of violence, permitting more radicalism.

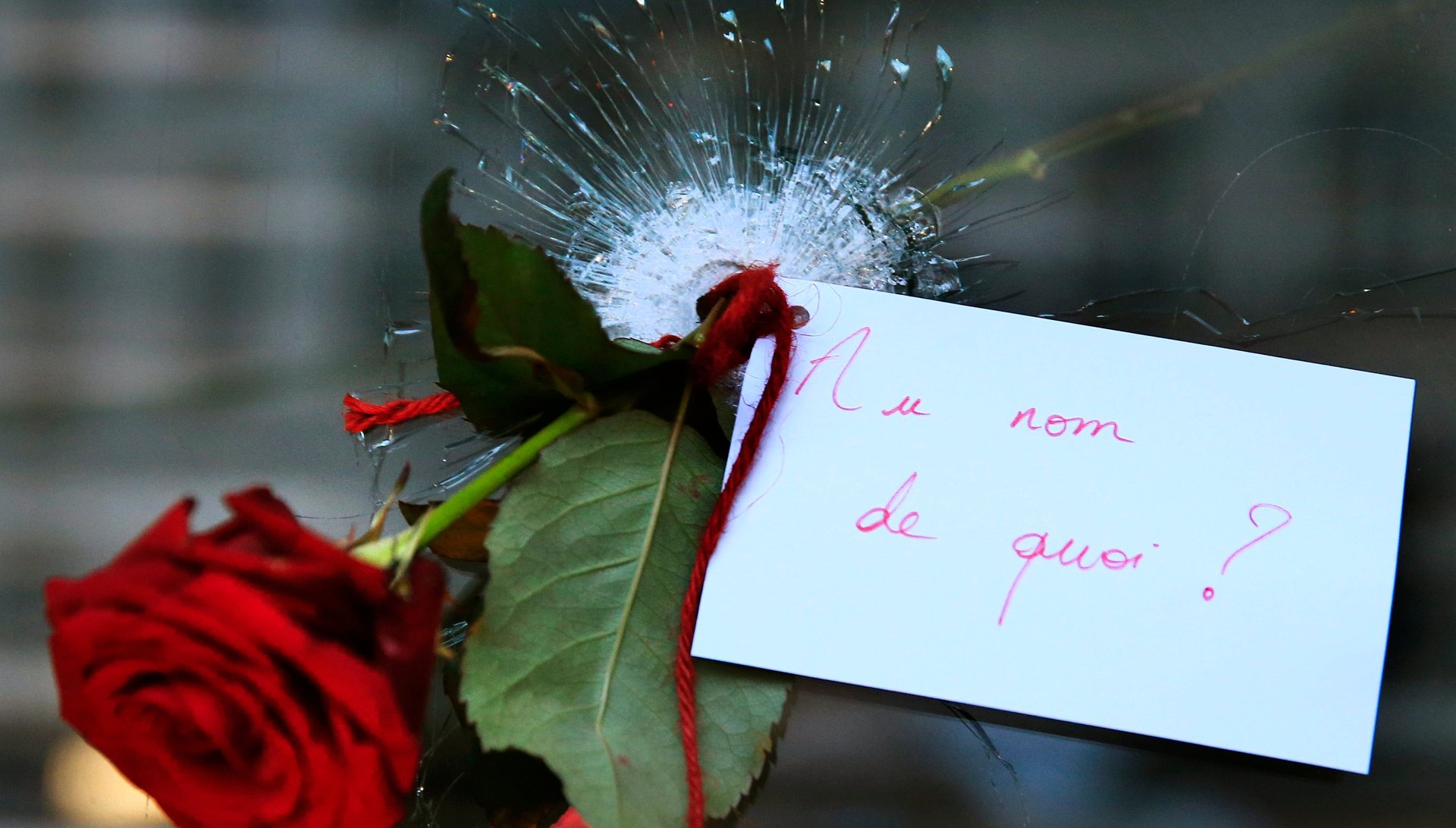

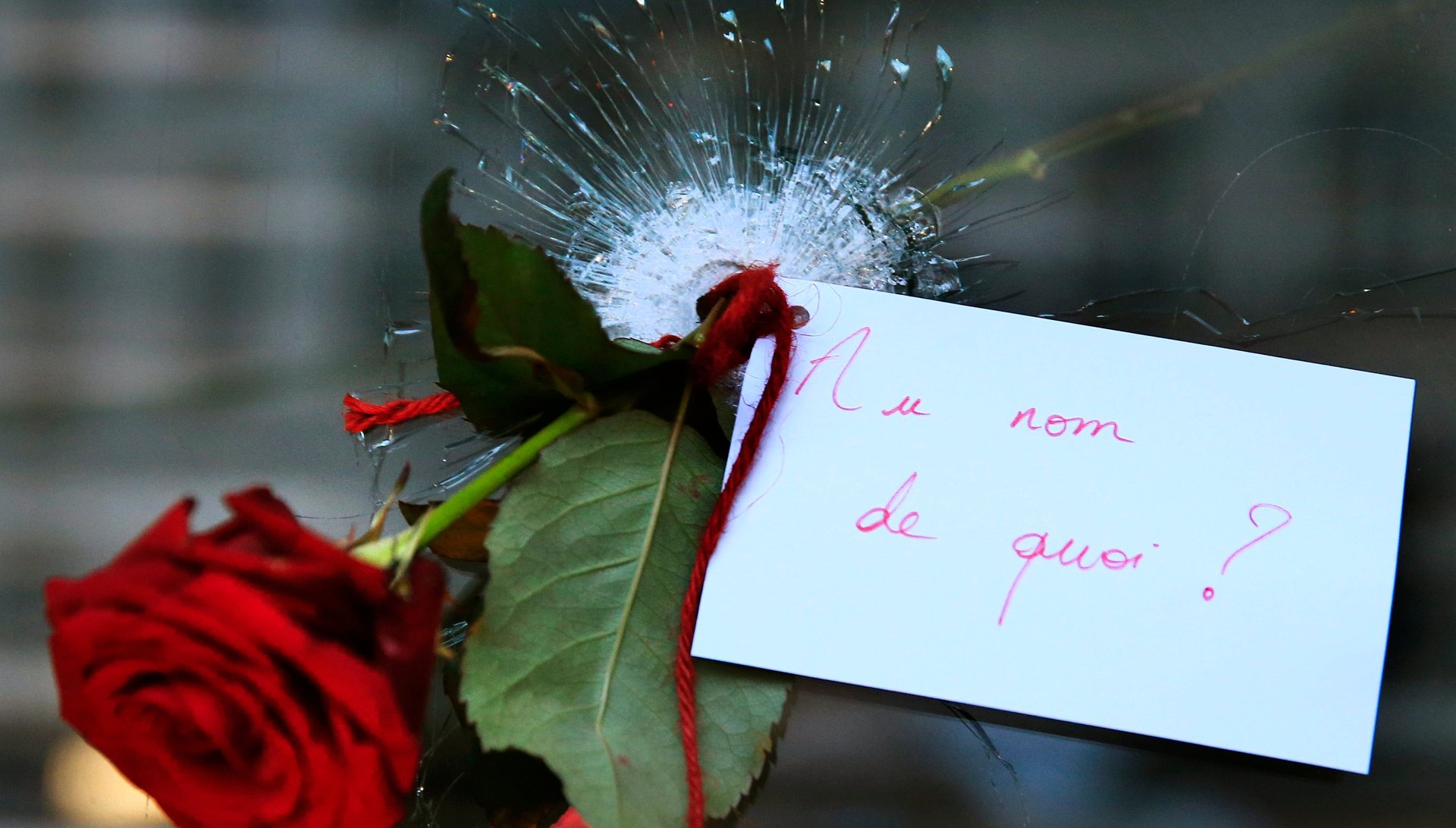

In France, the logic is the same. But why is France repeatedly singled out? Here there is a repetition of the strategy of exclusion, even as more worrying possibilities must also be considered. This attack is what we mean we talk about terrorism: Violence, which apparently cannot be predicted, which strikes all across the heart of an open city, cutting people down on a Friday evening, whether in a theater or at a restaurant. Violence which strikes at the romantic, cultural center of the West: the City of Light itself. But it’s about more than just symbolism.

France is home to what is likely Western Europe’s largest Muslim population, which has also long been among Europe’s most alienated. ISIL wishes to amplify mistrust in order to reap the damaged fruit. The attacks on Paris not only endanger innocent civilians, but have the ability to leave in their wake a climate of suspicion that could push intolerance over the edge.

The resulting mistrust is what ISIL seeks, hopes for, needs. In a country where a disproportionate percentage of prison inmates are Muslim—and which has struggled to control radicalizing influences behind bars–it may even increase recruitment, which will increase violence, which will increase recruitment.

A perpetual motion machine of evil.

But there is another consideration that must be brought to bear. France is a great country that has survived greater challenges in the past, which means France can and will triumph against this scourge. But France must also admit to a Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) strategy that is failing and to intelligence services that have permitted yet another major intelligence failure in under a year. The Charlie Hebdo terror attacks and the assault on a Jewish supermarket came first, then a Moroccan gunman on a train who could have wreaked havoc had it not been for the entirely fortunate but unplanned presence of brave Americans and Britons.

And now a catastrophic intelligence failure, a highly coordinated, sophisticated and organized operation, part of which struck at a stadium at which the French president himself was present.

It is of course alarming that ISIL can inflict this kind of damage. But an operation this large would have required tremendous planning—and yet it was never uncovered. This may be because the French have been more concerned with attacking social conservatism, and confusing religiosity for extremism, which is an all too common and unfortunate mistake. There are likely other causes at work as well. It takes a lot of powder to fill a powder keg.

The United States’ far more nuanced counter-terrorism strategy has proven (arguably) more successful than that of many of our Western allies. It is no coincidence that part of this strategy is to bring American Muslims on board as partners, not as suspects. The Organization of Islamic Cooperation recently announced plans for a dedicated center to combating extremist propaganda. These are examples of a global response to what, as we’ve seen, has become a global challenge.

France should work alongside these partners and rework its counter-terrorism strategy, because yesterday’s attack was not only vile and disgusting, but a worrying indication of how vulnerable France’s capital is.

It does not have to be.

ISIL would like for us to believe we are engaged in a civilizational struggle. It would like us to believe this is a battle between Islam and the West, even as ISIL kills people who are Muslim, or Western, or Western and Muslim. ISIL would like for us to turn on each other in suspicion and confusion. We know what they want, who they really are, and what they hope to accomplish.

We will not allow them.