This 24-year old Russian pianist may be classical music’s best hope at a revival

The holiday season is the one time in the year when classical music interrupts the regularly scheduled Adele-Bieber-Drake program. Classical music’s popularity has been on a continuous decline in the mainstream for several decades, despite various scientific studies extolling its neurological benefits. In 2014, one incendiary Slate article declared the whole genre dead.

The holiday season is the one time in the year when classical music interrupts the regularly scheduled Adele-Bieber-Drake program. Classical music’s popularity has been on a continuous decline in the mainstream for several decades, despite various scientific studies extolling its neurological benefits. In 2014, one incendiary Slate article declared the whole genre dead.

But last month, a slight, 24-year-old Russian pianist pulled off a small miracle. Playing three electrifying Rachmaninoff programs under different conductors at the New York Philharmonic for three successive weeks, Daniil Trifonov packed the 2,738-seat concert hall to near capacity, gained countless standing ovations at every performance (even at intermission), and resurrected a zeal for classical music, including new, curious listeners, even if only for the duration of his concert run.

Trifonov, who was just nominated for a Grammy, is a fast-rising star in the classical music scene. The genial, soft-spoken pianist is exciting to watch in action, his technical precision and stamina matched only by his ability to embody the character of the music. Several times during one of the Rachmaninoff performances, Trifonov becomes so possessed by a passage that he rises a few inches off his seat.

In a video of the rehearsal for Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Trifonov looks diabolical, drenched in sweat as he channels Niccolò Paganini—an 18th-century violinist so supernaturally gifted that he was accused of having made a pact with the devil. Reaching another passage, he plays with such tenderness his face takes on an angelic expression.

A child of professional musicians, Trifonov started playing the piano at age five and invests a lot of time in what he calls “emotional preparation” for every performance. “For the second round I started swimming in the fitness center,” he tells Quartz, describing the regimen he followed for Piano Concerto No. 4, a dramatic piece with long extended segments.

For his finale, Rachmaninoff’s daunting 45-minute Piano Concerto No. 3, (originally written by Rachmaninoff’ to show off his ”keyboard stamina” and extra-wide hand span, and today considered the piano soloist’s Mount Everest), Trifonov says he did a lot of body stretching.

His performances worldwide have been so consistently captivating that the London Times‘ senior music critic declared Trifonov “without question the most astounding young pianist of our age.”

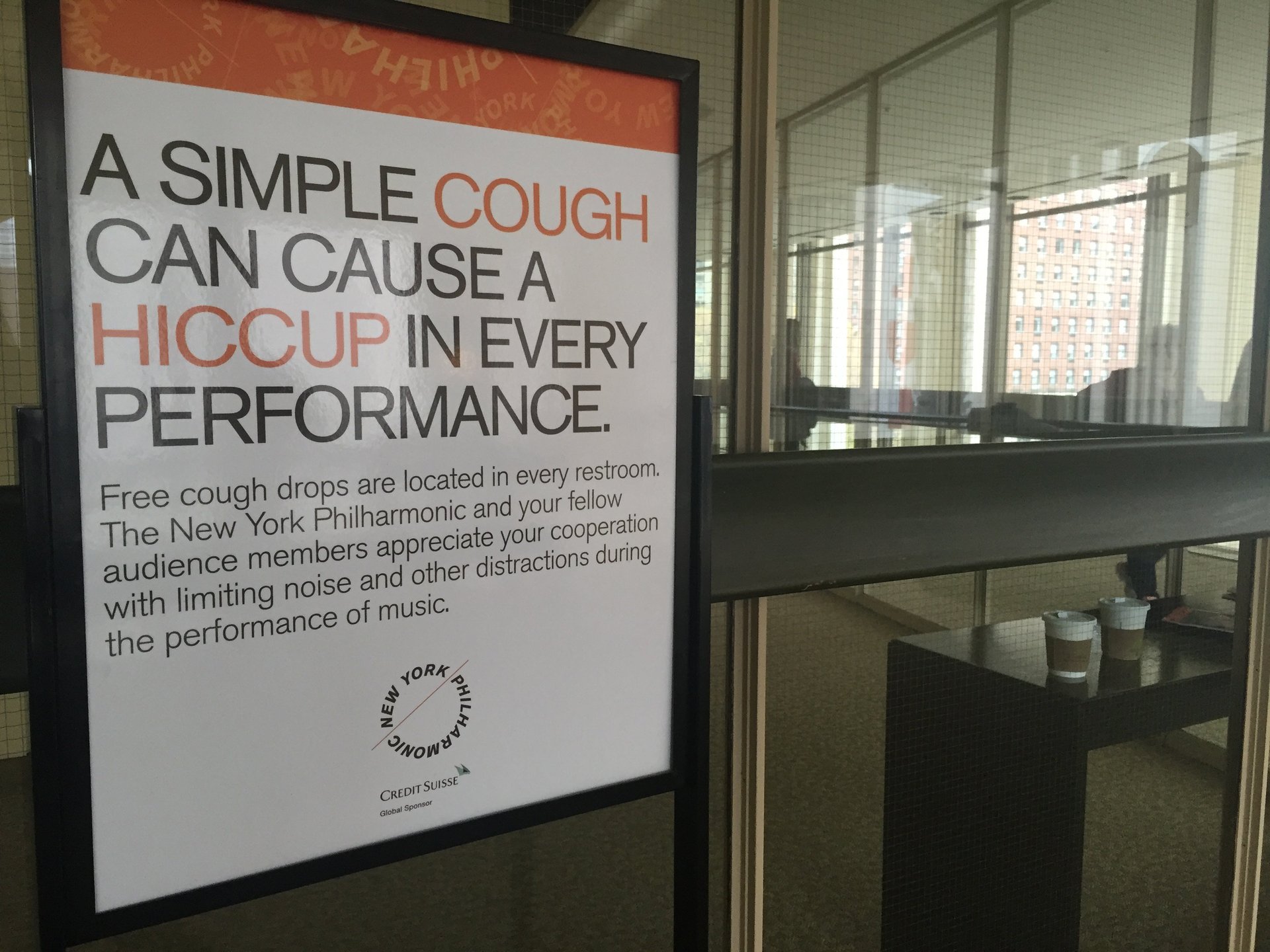

But apart from his talent, Trifonov’s appeal may also have something to do with his youth. Born in 1991, the award-winning pianist is among the youngest soloists in the professional classical music circuit today. A Millennial, Trifonov, plays for audiences with average age hovering around 49 in the US and 61 in France (French). Despite the symphony’s best efforts to lure younger audiences with cheap tickets, classical music concert halls for the most part are dominated by older adults and retirees. During an open rehearsal for Trifonov’s second concert, the announcer asked the audience to silence their cellphones and turn down their hearing aids.

Some conjecture that classical music’s waning popularity is related to its perceived elitism and anachronistic rules. Formality still reigns at the symphony with designated moments for applauding and clearing one’s throat, a far cry from the exuberant crowds in classical music performances a century ago. In the 1890s, screaming audiences stood on chairs for composer Richard Wagner and festooned concert halls with homemade fan banners, as cultural historian Joseph Horowitz describes in his book Moral Fire.

But perhaps it has something to do with our dwindling attention span, too. In a classical music performance, a movement can last up to ten times the length of a pop song. Just as Trifonov prepares for the physical challenges of symphonic performance, so must audiences on their way to a holiday concert or a performance of the Nutcracker this winter must train not to twitch, cough, text, or tweet for hours at a time—a challenge for the hyper-connected generation in particular.

Trifonov says that while he’s grateful for a big crowd, he’s even more grateful for an attentive audience. “[The] classical music audience is a dedicated one, people who listen to classical music do so intentionally,” reflects Trifonov. “The most important thing for me is not the quantity of people who come but how interested they are.”