A California judge ruled a woman can’t use frozen embryos against her ex’s wishes

A woman in California who wanted to use frozen embryos to become pregnant against her ex-husband’s wishes lost her legal battle in a San Francisco courtroom yesterday, Nov. 18.

A woman in California who wanted to use frozen embryos to become pregnant against her ex-husband’s wishes lost her legal battle in a San Francisco courtroom yesterday, Nov. 18.

A judge has ordered the five embryos in question destroyed.

“It is a disturbing consequence of modern biological technology that the fate of nascent human life, which the embryos in this case represent, must be determined in a court by reference to cold legal principles,” Superior Court Judge Anne-Christine Massullo wrote in her decision.

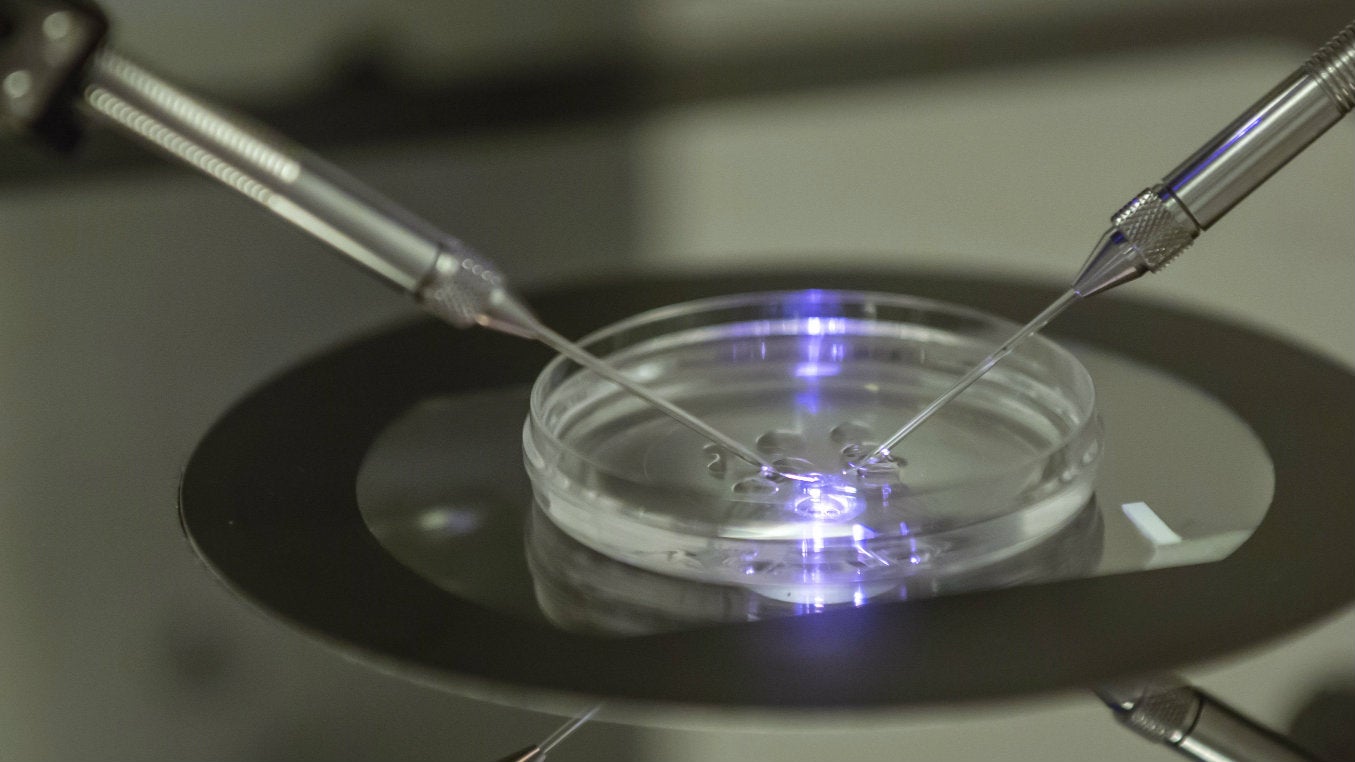

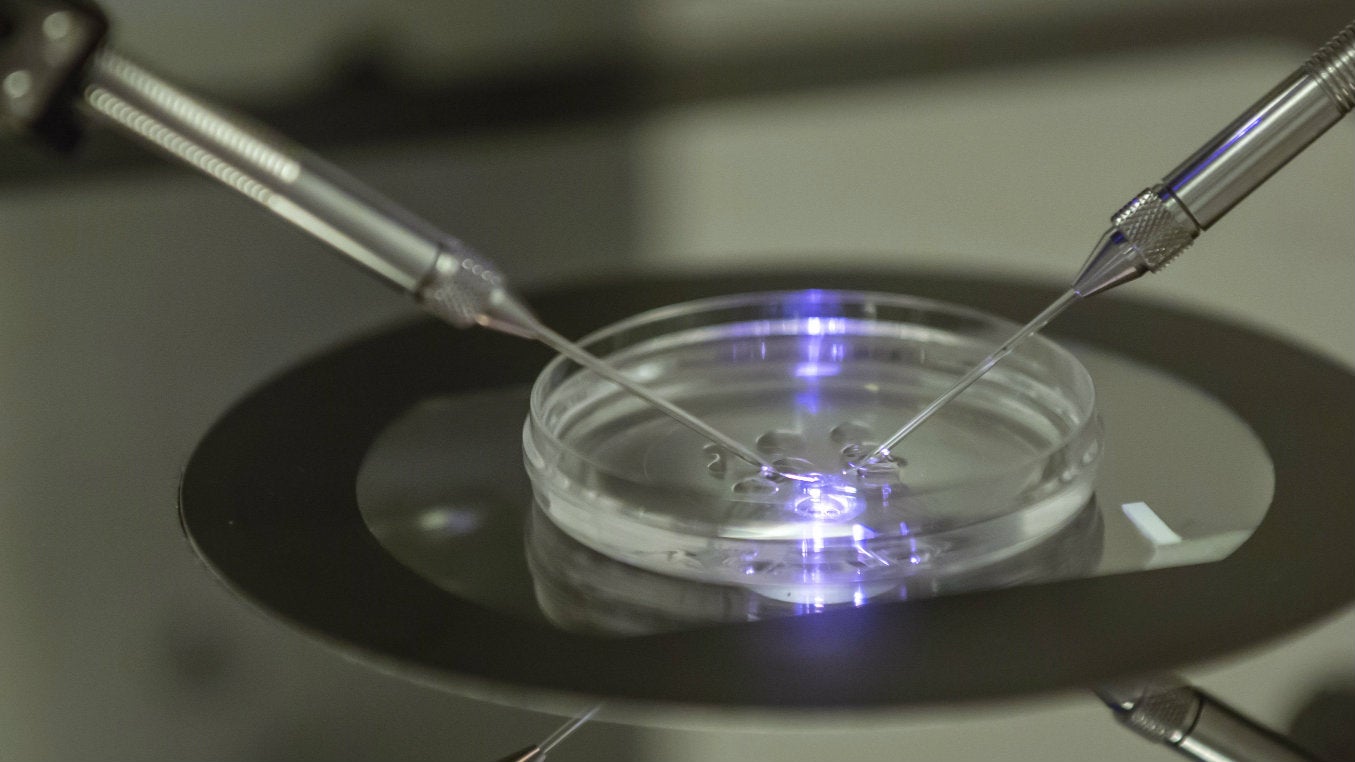

Shortly before her 2010 marriage to Stephen Findley, Mimi C. Lee discovered she had breast cancer. As a hedge against possible infertility, the couple chose to freeze embryos created through in vitro fertilization at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) hospital.

At the time, they signed an agreement with UCSF that the embryos would be destroyed, in case of divorce.

The marriage ended earlier this year. But Lee, 46, said she still wanted to use the embryos, as age would prevent her from otherwise having a biological child. Findley objected, arguing that he did not wish to have a child with his former partner and the contract between them should be honored.

The trial took place this summer. Behind the private and personal acrimony between two ex-spouses loomed a larger question: when science takes the need for two people to even be in the same room out of the reproductive equation, does the right of one party to procreate—frequently upheld in the courts—trump the other party’s objections? And does consenting to create an embryo with another person imply consent to use that embryo to bring a child to term?

In most disputes in the US, courts have said no, ruling in favor of the party unwilling to become a parent. In select cases, judges have awarded custody of embryos to partners who believed the cells were their only hope of producing biological children.

As the prevalence of IVF takes off—and as companies start to offer egg freezing as part of their benefit packages—these cases will likely become more frequent. UCSF alone already has some 100,000 embryos in storage.

The Lee-Findley dispute was the first such case in California, home to many IVF clinics. Lawyers and doctors are watching closely to see what precedent it establishes, especially if it moves to a higher court. Lee previously indicated that she would appeal if she lost.