The secret history of spots, stripes and other everyday patterns

The honeycomb design on breakfast cereal, the fleur-de-lis spikes on an iron gate, a constellation of guilloché spirals on our banknotes—if we look close enough, most of our built environment is embossed or embellished with some kind of pattern. But behind those everyday patterns are surprising, sometimes scandalous stories.

The honeycomb design on breakfast cereal, the fleur-de-lis spikes on an iron gate, a constellation of guilloché spirals on our banknotes—if we look close enough, most of our built environment is embossed or embellished with some kind of pattern. But behind those everyday patterns are surprising, sometimes scandalous stories.

“We literally wear these stories on our backs—and we haven’t yet begun to read them,” observes Jude Stewart, author of Patternalia, An Unconventional History of Polka Dots, Stripes, Plaid, Camouflage, & Other Graphic Patterns, a new book that dives into the history of these oft-overlooked design motifs of everyday life.

As it turns out, cheerful polka dots once signaled disease. English royalty’s posh sport coat pattern of choice, the houndstooth, originated from the commoners. And those preppy stripes were reserved for prisoners and prostitutes in the medieval ages.

“The ordinary world is crammed with surprises. Pattern is a perfect example of that: quiet, elided over, but revelatory when you dive in,” Stewart tells Quartz.

Stewart spent several years excavating the layered history behind Western civilization’s most common patterns. She describes the research process as “nutso,” dependent on intuitive, improvisational detours into libraries and archives:

You’re dependent on hunches, librarians who dig your off-beat question and help you riff on it, and your own patience to plow through books that really aren’t intended for you. Searching methodologically for surprises is an odd business.

Mirroring her own serendipitous research methodology, Stewart designed Patternalia to facilitate the reader’s discovery of everyday surprises. The compact volume is organized with a loose associative scheme—one historical episode leading to another, often not in chronological order. Each entry contains footnotes that lure readers to skip another section and form a unique thread, or, well, patterns of learning.

From the pages of Patternalia, here are some plainly fascinating facts about our patterned universe:

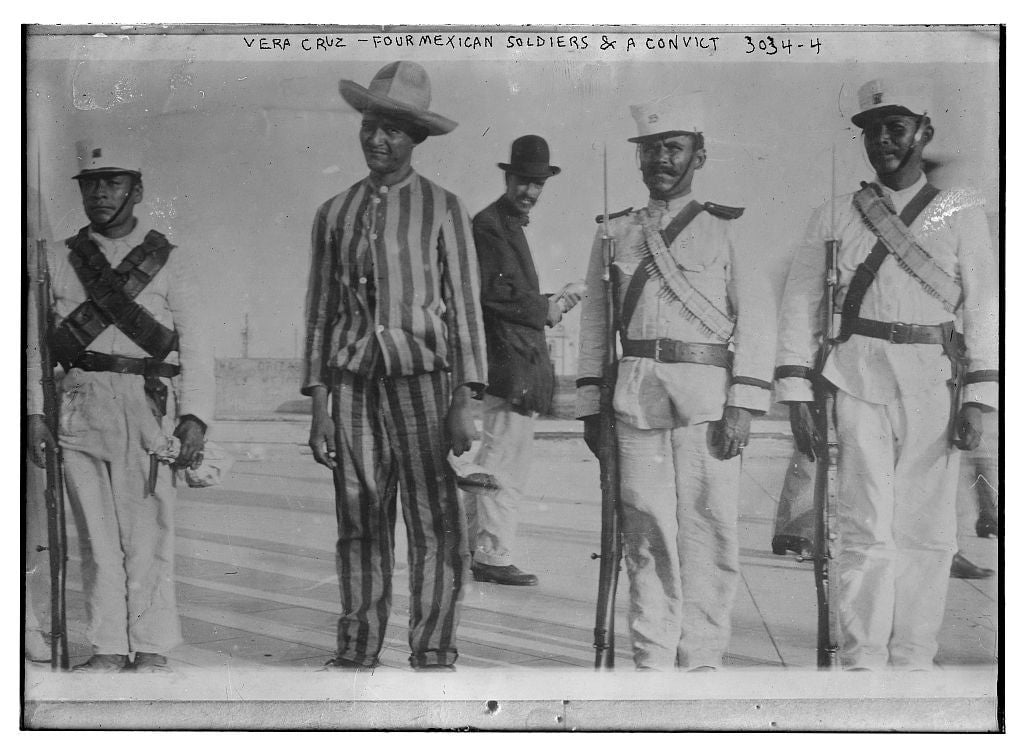

Stripes were once for prisoners and outcasts

By the 13th century the bias against stripes was well entrenched in Europe’s sumptuary laws, its literary conventions, and its artwork: Disreputable guys and slutty girls were helpfully depicted wearing stripes to signal their outsider status.

The pattern’s high visibility discouraged escape attempts while serving prisoners a daily dose of humiliation. “The horizontal stripes of black and white, applied in such broad widths, appear vulgar and brash—something undignified imposed upon the wearer,” write Mark Hampshire and Keith Stephenson in Communicating with Pattern: Stripes.

Polka dots represented blemishes, pox and disease

The innocent, bouncing polka dot is rooted in earthier stuff. Medieval Europeans rarely wore dotted patterns on fabric, because it was virtually impossible to space the dots evenly without the help of machines. In an era of iffy medicine, irregularly spaced dots made people think of outbreaks of incurable diseases like leprosy, syphilis, smallpox, bubonic plague, and measles.

Steven Connor, professor of English and cultural historian at the University of Cambridge, explains: “Irregularly spotted fabrics are ominous not just be cause they are reminiscent of blemishes on the skin, but also because they are uncomfortable reminders of the ominous markings of other fabrics: the blood in the handkerchief that was a traditional sign of tuberculosis, and the ‘spotting’…which may presage a miscarriage in early pregnancy.

The fleur-de-lis marked felons

Fleur-de-lis didn’t merely fancy up the aristocracy’s stuff. It also marked hardened criminals, slaves, and anyone controlled by the French state.

The practice of fleurdeliser (a verb meaning “to mark with the fleur-de-lis”) traveled across the waters to French-controlled colonies, including America. Under the Code Noir of 1685, African slaves in these regions were not tattooed but branded with a fleur-de-lis as punishment for their first attempt at escape. It got much worse: On their second attempt, their hamstrings were severed; on strike three they were killed.

Paisley was a pattern of plenty

The symbol sprang up millennia ago, somewhere between present-day Iran and the Kashmiri region straddling the Indian-Pakistani border. Although it was originally called būtā or boteh, meaning “flower,” in paisley people have seen resemblances to a lotus, a mango, a leech, a yin and yang, a dragon, a cypress pine. Ancient Babylonians likened it to an uncurling date palm shoot. Providing them with food, wine, wood, paper, thatch, and string—all of life’s necessities—date palms symbolized prosperity and plenty.

Paisley-the-Town’s [in Scotland] dominance in shawl production explains how the boteh pattern got renamed “paisley”throughout the Western world. (Europeans also used the word “paisley” interchangeably with “shawl”—as in, “Gertrude, your paisley is crooked.”)

The pattern acquired other nicknames and associations in its migration westward: The French called it at one point “tadpole,” the Viennese, “little onion.”

Houndstooth: exactly what it says

Houndstooth’s origins are hazy, but earliest wearers were probably shepherds in the Scottish Highlands, who liked how splashed mud wasn’t too noticeable on houndstooth outerwear. As the name implies, “houndstooth” got its name from its resemblance to the jagged back teeth of hunting hounds, although the pattern also goes by other names: “shepherd’s plaid,” “four-in-four check,” “gun club check,” and (adorably) “puppytooth” when it’s smaller in scale. To the French it’s called pied de poule, “chicken foot.”

Houndstooth climbed up the social ladder when English gentry adopted it as sensible but natty hunting wear. It got another boost when Edward, Duke of Windsor (he of Wallis-Simpson-throne-abdicating fame) started using houndstooth as a formal suiting material, far from the mucky fens of the English countryside.

Excerpts, Copyright 2015 Jude Stewart. Used with permission by Bloomsbury Publishing.