A Columbia University dean says ExxonMobil’s ethics allegations against the school are false

A Columbia University dean says ExxonMobil is knowingly making “false” allegations of ethical misconduct about a journalism instructor and a group of graduate students.

A Columbia University dean says ExxonMobil is knowingly making “false” allegations of ethical misconduct about a journalism instructor and a group of graduate students.

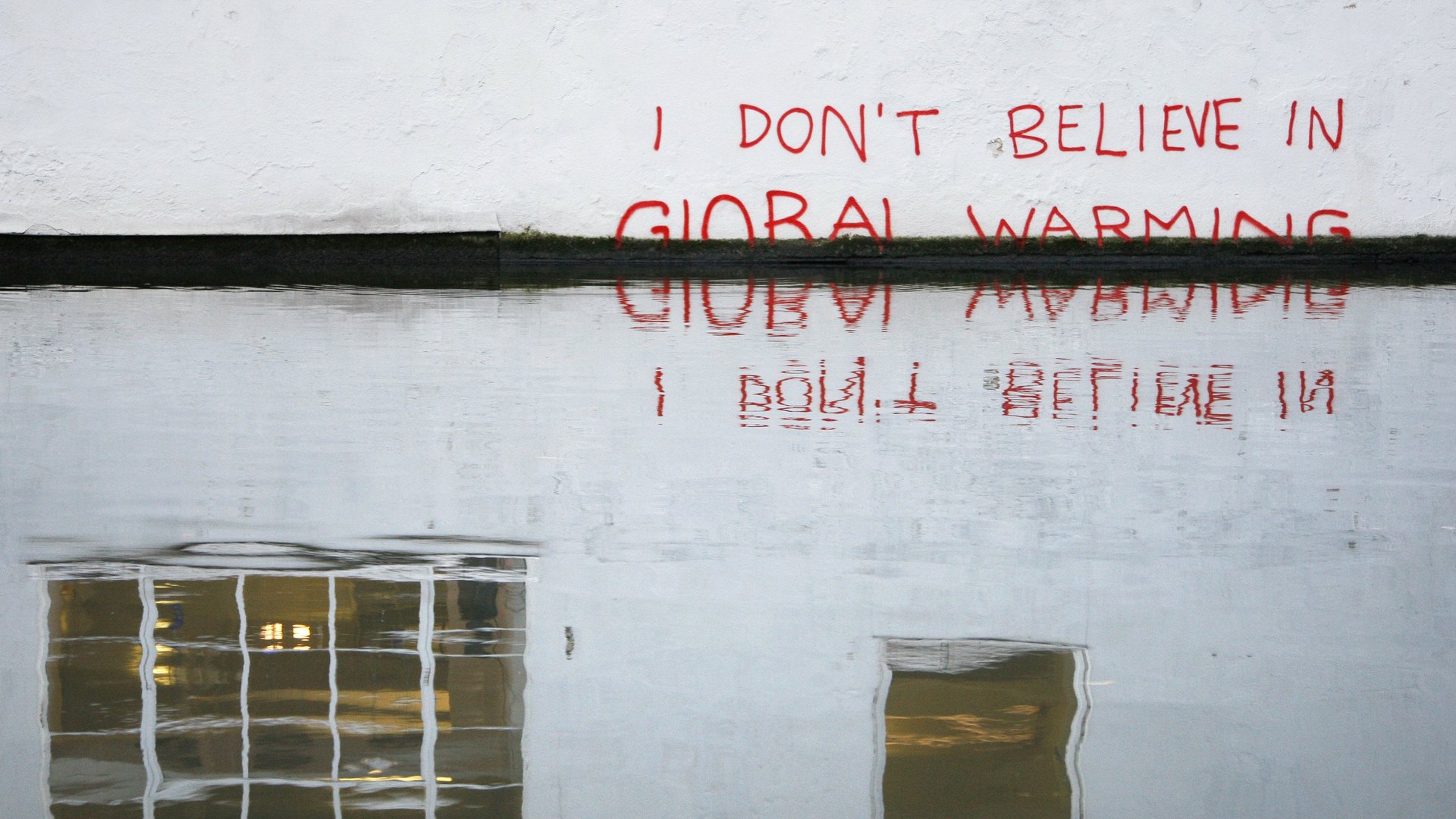

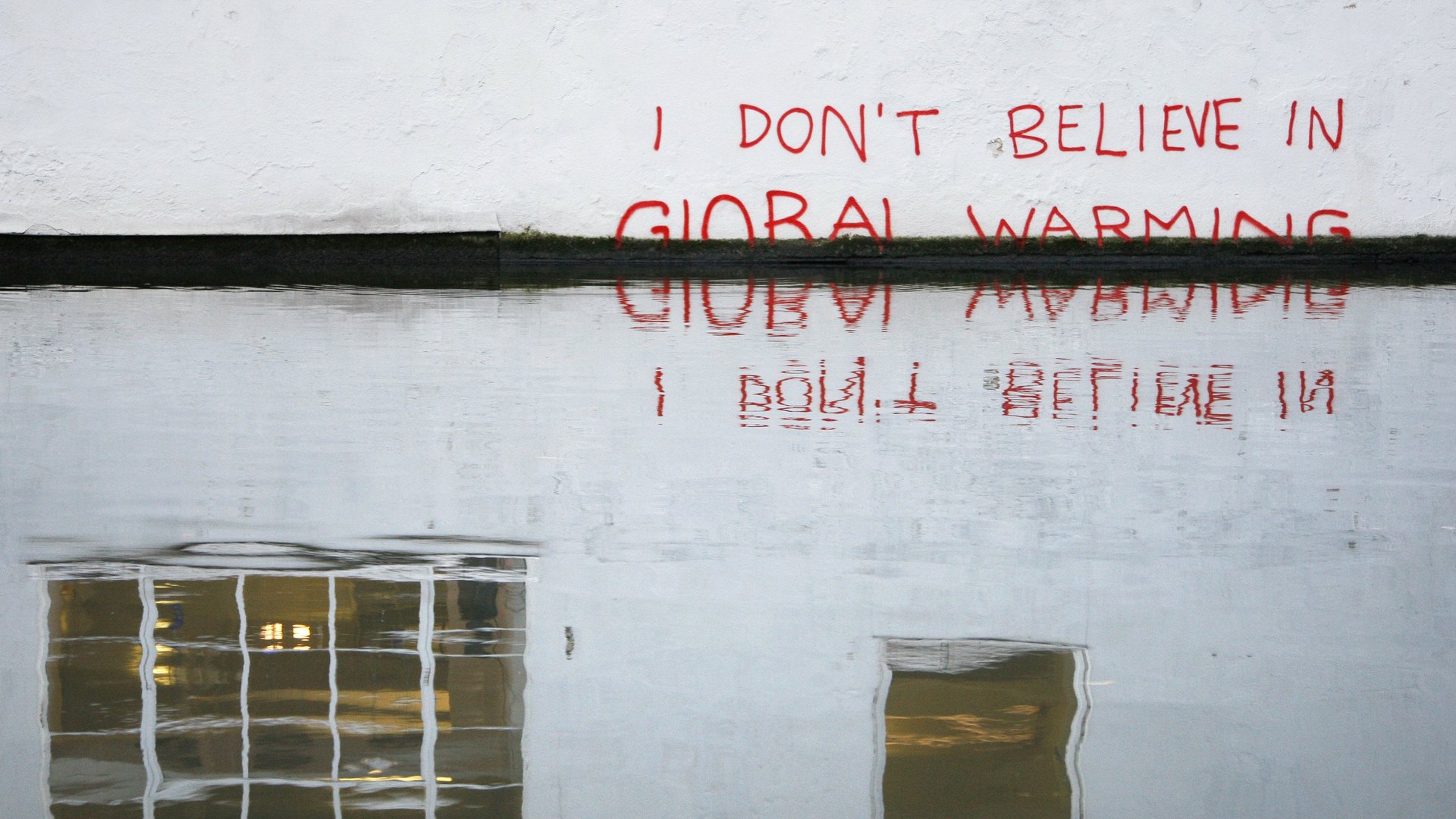

The unusually sharp exchange, related to recent articles about ExxonMobil’s climate change research, comes at a sensitive time for the company as world leaders gather in Paris to sign an accord reducing emissions from the burning of fossil fuels.

Steve Coll, dean of Columbia’s journalism school, made the remarks Dec. 1 in a six-page letter to an ExxonMobil executive. The letter is in response to Ken Cohen’s six-page complaint Nov. 20 to Columbia president Lee Bollinger about a pair of articles, published in October as part of a joint project between Columbia’s journalism school and the Los Angeles Times.

The articles suggest that ExxonMobil observed a dual policy on climate change: Externally, the company, led from 1993 to 2005 by CEO Lee Raymond, scornfully dismissed increasing concerns about climate change, and funded research that challenged climate science. Internally, however, company employees conducted ground-breaking climate studies, with conclusions that were far less clear cut. In at least one case in Canada, ExxonMobil’s majority-owned affiliate incorporated climate science projections into its oil development plans, one of the articles reported.

New York’s attorney general has initiated an investigation into whether ExxonMobil hid the potential perils of climate change from its shareholders and the public. Several congressman want the US Department of Justice to investigate as well. In response, Exxon has hired a high-profile corporate defense lawyer.

ExxonMobil’s Cohen, who in the 1990s directed some of the company’s public policy program that pushed back against climate science, has forcefully rejected the articles and similar stories published around the same time by Inside Climate News. Cohen has accused the journalists involved of deliberately skewing their findings and other ethical misconduct. The allegations are especially serious because US libel law requires, among other things, a judicial finding of willful disregard of the truth.

The company rejected the accusation that its internal and external positions differed, and said its policies evolved as climate science itself did. In the letter to Bollinger, Exxon’s Cohen said, “It is my understanding that Columbia University’s research policy forbids manipulation of research materials as well as ‘the change or omission or data or results such that the research is not accurately represented in the research record.'” It went on,

I am writing to bring to your attention what appears to be a clear violation of your policy by a Columbia faculty member and a team of graduate students at Columbia who compiled two inaccurate and deliberately misleading reports about ExxonMobil’s climate change research.

In his rejoinder, Coll said that his team had done nothing of the kind.

“I have been troubled to discover that you have made serious allegations of professional misconduct in your letter against members of the project team even though you or your media relations colleagues possess email records showing that your allegations are false,” Coll wrote.

The letter goes on to detail the long email and telephone exchanges between reporters and ExxonMobil’s PR team before the articles were published, and other specifics, before concluding: “What your letter advocates really is that the factual information accurately reported in the article, and unchallenged by you, be interpreted differently.”

In an email to Quartz, ExxonMobil spokesman Alan Jeffers said, “We stand by the (Nov. 20) letter and do not consider our issues addressed or resolved.”