‘A room unoccupied is wasted air’: How you can make the most of minimal living space

Between July 2011 and August 2015 I lived in a ~400sqft studio apartment in San Francisco. I moved in a bachelor but by the time I moved out, I was one member of a four person family. Here are some things I learned along the way.

Between July 2011 and August 2015 I lived in a ~400sqft studio apartment in San Francisco. I moved in a bachelor but by the time I moved out, I was one member of a four person family. Here are some things I learned along the way.

Lesson #1: Rent control has strange side effects

San Francisco has a rent control policy that prohibits most landlords from raising rent more than ~1% per year. The goal is to help fight against families getting displaced.

When my wife and I got married and she moved in, we considered moving. Our budget had increased some, but our purchasing power had dropped. We could change neighborhoods, but we’d be sacrificing in apartment quality. We decided to stay.

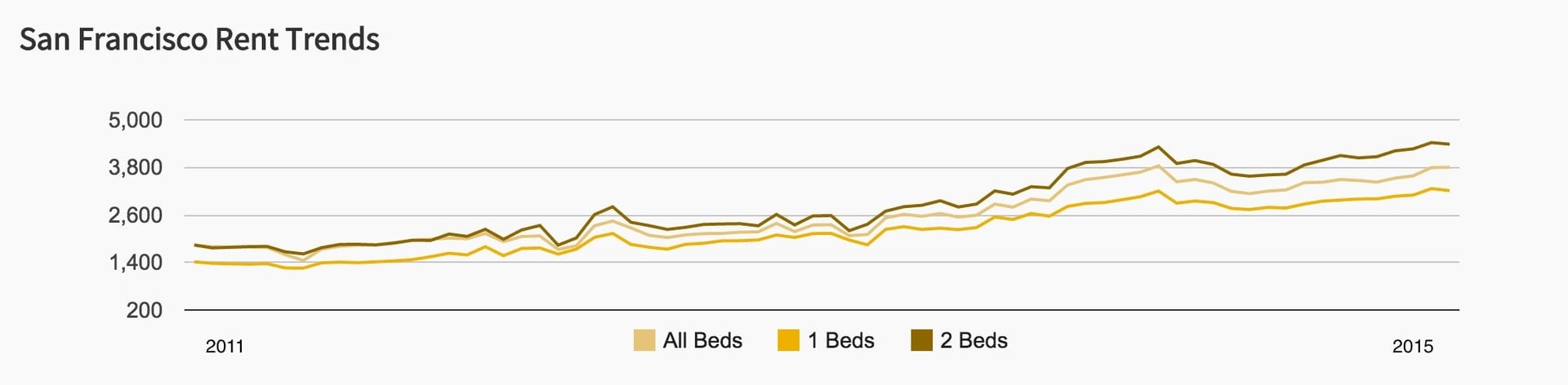

A year and a half later, we welcomed our first son into the world. At that point rent in the city had risen by over 50%. We were dropping to one income so my wife could be a full time mom, and we chose not to shoulder a rent increase simultaneously.

Babies are not very big. He wouldn’t take up much space.

So I built us a custom bed in the closet and we put the baby bassinet in the main room. We became very good at whispering.

Seven months after Hunter was born, we found out we would be having another baby. Part of our plan, but maybe a bit sooner than expected. Sometimes those things take a while, and sometimes they don’t.

As the pregnancy progressed, our oldest son started walking and, like his dad, was very active. Staying seemed impossible.

We searched. We explored all options. The trouble is rent had gone up a ton so we weren’t going to be able to afford to stay in our neighborhood. (Please note my definition of the word “afford” might be slightly different than yours.)

Let me give you some perspective.

When I moved in, a studio in San Francisco cost ~$1,200-1,500. ~$3 per square foot per month. By the summer of 2015 a two bedroom in our neighborhood of San Francisco would fetch ~$4,000-5,000. $5.50 per square foot per month. That is a big increase in itself. But when you do some algebra to figure out the cost per square foot gained, it gets even bigger. For those extra 400 square feet, we’d be paying $3,200 or $8 per square foot per month.

Essentially we’d have to pay four times as much rent for twice as much apartment. A tough bite to swallow.

Thanks to rent control, we had low rent on our studio. But thanks to rent control, we were financially disincentivized from moving anywhere else. It was a very strange feeling.

We explored other options: doubling my commute, or moving to a neighborhood with higher crime rates.

In the end we decided to make it work for a bit longer. We had hoped a raise at work, a transfer to a new location, or possibly changing companies would make things easier. We needed about six months to explore options, come to a decision, and implement a change.

Necessity is the mother of invention.

Lesson #2: Deviations from the local norm are costly

My wife and I were 27 when our first son was born—significantly younger than the median San Francisco birthing age of 33. We also made a decision to have my wife stay at home with the children.

Neither of those things are strange for a family in the United States during the last century. But both of those are strange for a San Franciscan in 2015.

I didn’t realize all of the effects that decision would have on our lives in San Francisco. There is probably enough there to fill a blog post, but when it comes to apartments, it meant that it was even harder for us to find a place to live.

Our competition for two bedroom apartments in San Francisco was fierce to begin with. Sure, it is expensive, but for us it wasn’t a matter of not being able to afford places. We would apply to places and not get selected.

One of the key criteria landlords look at is total income, and since we had one income, we had a steep disadvantage over working roommates and DINKs (dual income, no kids).

We would show up to open houses for two bedroom apartments with our application filled out, only to find 20 other people doing the same. Landlords had their choice, and the place would inevitably go to a pair of young professionals with combined salaries somewhere in the low gazillions. Or maybe a family, but one decade older, a decade further in their career, and with a decade of extra raises and promotions under their belt.

Living outside the norm had put us at a disadvantage.

Lesson #3: There are two types of space in a house

Density is a thing not many people think about when it comes to their homes, but I came to realize that it was the most important measure of space.

Any time you have an optimization problem, you need to identify your limiting factors. In a house, it is density.

There are two very distinct types of space in a house: high density storage space and low density living space. In order to optimize a living space, every cubic foot should be pushed towards one of those boundaries.

Many people struggle with space because much more of their home volume occupies the awkward middle ground. Their living spaces are cluttered and their storage spaces are not packed. They try to solve their space constraints by getting a larger home, which is exactly like trying to solve a waistline problem by buying larger pants.

The space you can see in a house during your normal day is your living space. If it becomes more than 5-10% occupied by volume, it feels cluttered. Look around at the room you’re in and think about all of the air space—probably about 90%+ of the room. (If your house is cluttered, envision a picture of a room in a design magazine or on Pinterest)

This was a very important thing for me to realize in a small space. If we didn’t put things away, or if we acquired anything extra, the space felt cramped and our desire to move to a bigger space increased. It was a constant battle to keep this space as unoccupied as possible—always trying to reduce to get that number lower.

At the opposite end of the density spectrum is storage space. The ideal storage density is 100%. Achieving that is impossible, as the more dense the space gets, the harder accessing the items becomes. Consider that a cleared walkway to access items in fact reduces your density. That is why, to optimize, certain libraries have movable shelves where only one is accessible at a time—it maximizes storage space by reducing redundant access space.

Some storage space, like a closet, is obvious, but one trick I had was to make new storage space wherever possible. Our coffee table (seen two photos up), which sometimes doubled as a changing table, was made from an old trunk I put legs on. It perfectly fit all of our extra guest linens while serving its other roles—reducing the amount of non-used space. (Yes, we had overnight company—even post babies.) You can barely see a few tubs under the couch in a picture below. I ordered different legs for the couch so that the tubs would fit, giving us a few extra cubic feet of highly organized and easily accessible storage space.

When you think about those two types of space, you realize that your housing needs are dictated by the sum of your lower limit of living and storage space. You can dramatically reduce your housing size needs by forcing things towards those limits and then reducing either one.

Lesson #4: A room unoccupied is wasted air

Thinking just about living space, most houses have way too much. Remember, living space is usually only 10% occupied by what is in the room—the rest is air.

Since one person can only be in one room at a time—and often people aren’t home at all, or are gathered in one room—at any given point, most rooms in American houses are empty. That is a giant waste of space and money.

It can be solved through a number of means including:

- increasing the multi-purposefulness of spaces

- increasing the adaptability of space

- decreasing the number of things you need your living space to serve as

- decreasing the amount of simultaneous and different rooms you need to be in

Our living room doubled as our bedroom when we moved our son’s nursery into the closet. I designed it with the intent of keeping the perception of 10% density when you were sitting on the couch while avoiding reducing our floor space by the area of the bed.

I attempted a few tricks in order to have it pass the wife-threshold. (That magic bar that every home improvement project must clear in order to have any chance at survival.)

The bookshelves behind the head double as the space underneath our headboard shelf. It gives you something to look at when you walk in the room other than a bed, and kept the pillows from falling off.

I also minimized the number of support beams on the front and sides—you can see there is nothing coming off the leg closest to you. That reduced the feeling of clutter and decreased that chances of head-bonking.

I also built stairs that doubled as a bookshelf and since they had no backing, they let in a lot of light. The fact that they were stairs was critical as I built this when my wife was six months pregnant. She was able to get up there until the day before our second son was born.

The second method I mentioned above was adaptability. It is one I didn’t have a chance to experiment with, but I love these examples.

The idea is that your house changes shape to adapt to the current need. For example, a wall moves back and forth between a bedroom & living room so they are both larger when used without increasing the total space used.

I would have loved to have the loft bed on an adjustable riser system. The height it was at was sub-optimal for both living & sleeping. But that would have made the build much more complex and wasn’t in the cards for this period of life.

The final two ways to reduce living space involve reducing—the hardest step for most people, but easiest to get gains from.

The simpler your goals for a house, the easier it is to have a small house that provides them. Our living room didn’t need to serve as a TV room since we didn’t have a TV. That meant our furniture arrangement didn’t have to take into account seating positioning, cable inputs, or speaker placement.

Finally there is the factor of number of rooms occupied. This is the one that ultimately got us. As our family increased to four people, it became impossible for every person to be in a unique room. That posed significant challenges during nap time, bed time, and when having company over. We could have made it a bit longer, but this is the item that would have gotten us.

Lesson #5: Home is more than a place to keep “stuff”

The second limit of a living space is the need for storage of stuff (see: George Carlin). Consider that, by volume, your stuff occupies probably 50-200 times as much space as you do in your house. You would be able to get by fine with a smaller house if you either:

- increased the density of your storage space

- decreased the amount you needed to store

I already discussed the former point, but I’ll take a moment to reflect on the latter.

Our family had the constraint of an apartment that didn’t change size, even as we grew. Our adjustment into a small living space was gradual enough that we became accidental minimalists.

For three years, we donated at least one grocery bag per month to thrift stores, slowly paring down what we owned. As the space became tighter, the bar an object had to be above in order to earn a place in our house kept getting higher.

I started to really think about what I owned and why I owned it. I became a more conscientious owner of things. The possessions I own now are such a reduced and fine-tuned representation of my current needs that it is hard for me to find want for anything else.

As things got harder, I also found ways to hack the system. I now use craigslist as something between a rental shop & storage facility. Buying things for a season of life and selling them when I won’t need them for a while. I have often even turned a small profit doing so.

I also found ways to hack myself. A lot of the things I owned were in my house with the purpose of “I might need this someday.” I had to work hard to convince myself that I didn’t. In the end the compromise came down to this—”If you get rid of this and need it again, you have permission to buy it from Amazon with same day delivery”—so far that hasn’t happened.

Consider that you are paying rent for your stuff. That closet space, or worse yet, storage unit, is costing you money every month. Eventually you will spend more in storage than the contents ever cost you.

Lesson #6: Shared assets reward those that use them

The “shared economy” is a buzzword you will hear, but the idea is nothing new. Uber is to cars what city parks have long been to backyards.

While living in the studio, our family made heavy use of San Francisco parks. What I lacked in a yard I made up for on early mornings with our oldest son at any of the five parks in walking distance to us. Before I left for work, we would head to the basketball court where he would play with cars or chase a tennis ball around and I would work on my jump shot.

Speaking of shared assets, we live in an age where owning books, CDs, or DVDs is wasted space and money. Most media sits unused for the majority of its life. It was once the case that access to information was rare, which is why owning a library had a benefit. But now we have the Internet—round the clock access to more information and entertainment than you could ever consume. There is no need to own. Public libraries are free and there are plenty of ways to rent things when you need them.

Lesson #7: Less house means less housekeeping

Living in a studio apartment was hard. It took work, planning, organization, and commitment. But there was a silver lining. Having less house has benefits in reduced housework.

One of the most obvious is that there is less to clean. There are fewer shelves to dust and less floor to vacuum.

There also isn’t a need to furnish and decorate as much, which reduces stress, cost, and time spent planning.

There is also a decreased chance of clutter. Because everything happened in one room, if we didn’t clean up after ourselves, we couldn’t ignore the mess. We would put away the toys every night before my son went to bed so that we could sit in the living room afterwards and not stare at toys. As a strange side effect, our son loves cleaning up.

We didn’t lose things often. Living in a small space forced organization. Everything had a place and we all knew where that was. Even if you did misplace something in the house, there weren’t many places for it to hide. You would find it much faster than in a large space.

More house always comes with more house work. More yard with more yard work. In a world with finite time & money, reducing one thing allows you to increase another. Less time cleaning a house can mean more time living with the people in it.

Lesson #8: When living on tight margins, the highs are the same, but the lows are much lower

Thinking on all of our time in that apartment, I can recall many of my favorite times. None of them have much to do with the apartment—they all have to do with the people in it. Whether that was our family, my former roommate, visiting friends or extended family.

The highs we experienced were no different than any other family’s.

In contrast though, the lows were much lower.

Now, I don’t mean the personal lows one family might encounter: illness, strife, financial woes, etc. Those would likely be as low no matter where you are. I am specifically referring to the lows that are more directly tied to the living space.

In a small space, the typical day is ok, but there are such thin margins of free space and separation. There are times when all of this implodes. One thing going wrong can tip the next wrong domino and cause a chain reaction.

For example, consider the weekend in which I built the loft bed. In order to assemble it in the room, I needed to move everything out of the way, start attaching pieces, and stand things up against the wall while I started on another. There were screws and planks and sawdust everywhere. It took more than one day which meant there was a night where we neither had a finished loft bed nor room for a regular bed. Unfortunately I overestimated how much I could get done and had to leave for a business trip. Sunday night I took the red eye, leaving my pregnant wife at home with a toddler in a construction zone with no bed to sleep on. Not our happiest goodbye. (I had cleaned up most of the screws and some of the sawdust)

A final, and more humorous situation I would often find myself in was early morning meetings with nowhere to go. The 12 person startup I moved to San Francisco for has grown into an international software company. That meant I’d sometimes be needed for early morning meetings at 5 or 6a.m. My typical day, as is common with San Francisco tech companies, usually started closer to 9 or 10a.m. Rather than wake up at 4a.m. to get ready and head into the office before a 5a.m call, my strategy had been to take the call in my PJs and then get ready and commute afterwards.

That worked great when I was single, had a roommate, and even when my wife moved in. But once the babies came onto the scene, it was tough. You never want to wake a sleeping baby. I tried the bathroom, but the babies would wake up. The eventual solution was to take the call from my car in the garage. I am proud to say I’ve helped close million+ dollar software deals in my PJs sitting in a car parked in my garage. But there were definitely some days I would sit there thinking “What the heck am I doing right now?”

We had some really tough days, but in the end I live a life of many blessings. Reflecting on these days, however, has given me much more understanding for those living life with less. Whether rich or poor, a normal day is a normal day. When you’re wealthy and your car breaks down, you can get a rental. But when you’re poor, paid hourly, and your transportation fails—that sort of thing can just compound into a really bad situation. Sick days can mean extra expenses and lost earnings at the same time. I think there are a lot of misconceptions about poverty, and even lower-to-middle class working lives. If we better understood margin and variance, it would really help us become more sympathetic and caring people.

Lesson #9: Toughen up—it will be worth it

In cycling culture, there is a thing called ‘Rule V’ that states, “HTFU” (Harden The F-word-of-your-choice Up). It means that even though the hill is steep, it is cold and raining and you are tired, you toughen up and ride hard. If you want to be fast, that is what it takes. The hard work you put in that day makes you stronger for next time.

That rule very much defines my approach to life.

Living in a studio apartment with one or two babies was a constant challenge to HTFU. As I stated above, living in a small space was tough—there were days I wanted to give up. The space was too small, the noise was too much, there was nowhere to go to be alone. But fighting through those days is how I would get stronger for the next day.

Why is that important?

We humans have a strong ability to adapt, sometimes that actually works against us. If we live with a certain amount of luxury, we will become accustomed to it. The trouble with getting used to an easy or expensive way of living is that none of us know what is next.

In the startup world, we talk about something called “runway.” It basically means how much time you could keep operating if the money stopped coming in. For many companies, that time is very short. For many families, it is even shorter. That is an extremely vulnerable place to be.

The reason I think it is so important to always keep expenses down is that it has the dual effect of decreasing your burn rate and increasing your savings. The two of those combine to allow you more freedom. When you have a lot of financial runway, it allows you to make decisions based on reasons other than money.

There is some sum of money that, under the right conditions, you could live the rest of your life on. At that point you would never need to work again, but certainly could. That is true freedom.

Not everyone has a chance at freedom. Some people have to work long and hard just to scrape by. But many people repeatedly sign away their freedom by choice.

And don’t forget about the importance of compound interest. I will remind you that $2,000 per month saved on rent for one year is $24,000. Invested for 50 years averaging 6% interest comes to roughly $450,000. Freedom. HTFU.

Lesson #10: It doesn’t require a studio

A few months ago we moved out of San Francisco and that apartment. In the end there were a lot of reasons, only some of which were the limited space.

We ended up moving to a less expensive city (Seattle) and getting a two bedroom for much less than we had been considering in San Francisco. It feels huge. We don’t even know what to do with most of the space. Everything feels a bit careless in placement without the tight constraints that forced us to think very carefully.

But I am forever ruined. I will never again be able to think of a house in the same way. I will never be able to think of stuff in the same way. My definitions have all been altered.

And then there is you. You don’t have to live in a studio to benefit from these lessons (though perhaps that is how you found this post). Whatever space you occupy, perhaps there are thoughts above that shift your perception. It is those seeds of thought that can take root and grow into actions.

As my wife and I look at places we might want to live, we do so with new eyes. As we think about the future and situations we might want to steer our lives towards, our goals are now different. The sacrifices we might have to make to allow them seem less challenging. The trade-offs more manageable.

I am not sure what the future holds, but I have some ideas that I am very excited about. I will forever be grateful for that studio apparent, our kind landlords, and how that period of time helped shape the path we will walk.

This post originally appeared at GregKroleski.com.